Basic Principles of Detectors

There are three main types of detectors, which record different types of signals.

- Counter. The activity or intensity of radiation is measured in counts per second (cps). The best-known counter is the Geiger-Müller counter. In radiation counters, the generated signal from the incident radiation is created by counting the number of interactions occurring at the sensitive volume of the detector.

- Radiation Spectrometer. Spectrometers are devices designed to measure the spectral power distribution of a source, and the incident radiation generates a signal that determines the incident particle’s energy.

- Dosimeter. A radiation dosimeter is a device that measures exposure to ionizing radiation. Dosimeters usually record a dose, which is then absorbed radiation energy measured in grays (Gy) of the equivalent dose measured in sieverts (Sv) A personal dosimeter is a dosimeter, that is worn at the surface of the body by the person being monitored, and it records of the radiation dose received.

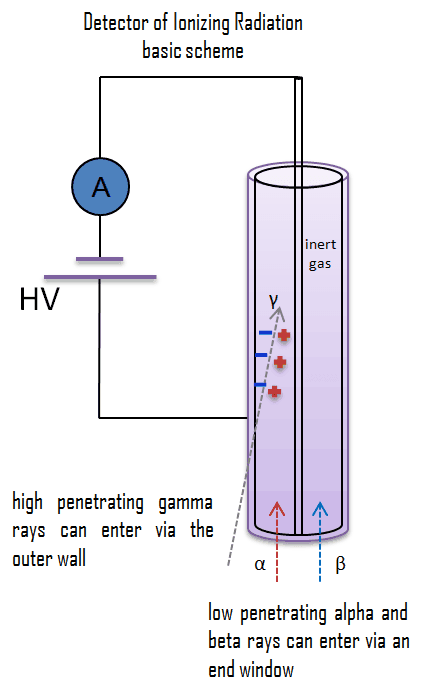

All these types of equipment require that the radiations result in observable changes in a compound (whether gas, liquid or solid). In their basic operation principles, most ionizing radiation detectors follow similar characteristics. Detectors of ionizing radiation consist of two parts that are usually connected. The first part consists of sensitive material, consisting of a compound that experiences changes when exposed to radiation. The other component is a device that converts these changes into measurable signals. All detectors require that radiation deposit some of its energy in sensitive material that forms part of the instrument. The radiation enters the detector, interacts with atoms of the detector material, and deposits some energy into sensitive material. Each event may generate a signal, a pulse, hole, light signal, ion pairs in a gas, and many others. The main task is to generate a sufficient signal, amplify it, and record it.

In this section, we describe many different types of radiation measuring instruments. We focus on the first part, which consists of sensitive material. Detectors may be categorized according to sensitive materials and methods that can be utilized to make a measurement:

- Gaseous Ionization Detectors

- Scintillation Detectors

- Semiconductor Detectors

- Film Badges

- TLD

Let’s assume gaseous ionization detectors. A basic gaseous ionization detector consists of a chamber filled with a suitable medium (air or a special fill gas) that can be easily ionized. As a general rule, the center wire is the positive electrode (anode), and the outer cylinder is the negative electrode (cathode), so that (negative) electrons are attracted to the center wire. Positive ions are attracted to the outer cylinder. The anode is at a positive voltage for the detector wall. As ionizing radiation enters the gas between the electrodes, a finite number of ion pairs are formed. Under the influence of the electric field, the positive ions will move toward the negatively charged electrode (outer cylinder), and the negative ions (electrons) will migrate toward the positive electrode (central wire). Collecting these ions will produce a charge on the electrodes and an electrical pulse across the detection circuit. However, it is a small signal. This signal can be amplified and then recorded using standard electronics.