What is Berkelium

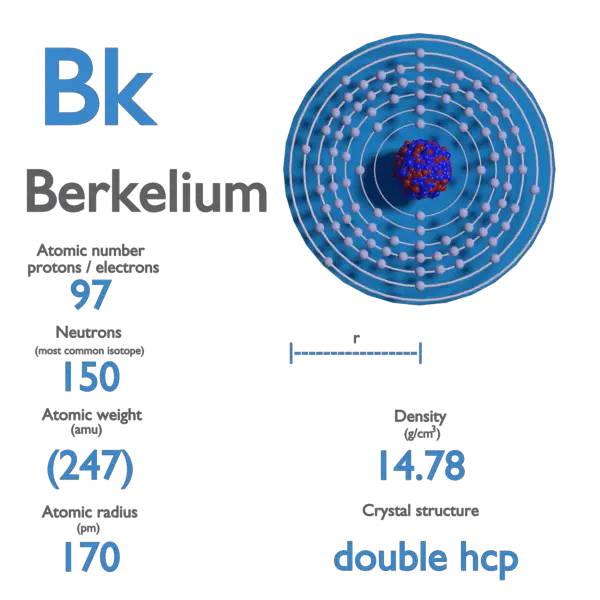

Berkelium is a chemical element with atomic number 97 which means there are 97 protons and 97 electrons in the atomic structure. The chemical symbol for Berkelium is Bk.

Berkelium is a member of the actinide and transuranium element series.

Berkelium – Properties

| Element | Berkelium |

|---|---|

| Atomic Number | 97 |

| Symbol | Bk |

| Element Category | Rare Earth Metal |

| Phase at STP | Synthetic |

| Atomic Mass [amu] | 247 |

| Density at STP [g/cm3] | 14.78 |

| Electron Configuration | [Rn] 5f9 7s2 |

| Possible Oxidation States | +3,4 |

| Electron Affinity [kJ/mol] | — |

| Electronegativity [Pauling scale] | 1.3 |

| 1st Ionization Energy [eV] | 6.23 |

| Year of Discovery | 1949 |

| Discoverer | Stanley G. Thompson, Glenn T. Seaborg, Kenneth Street, Jr., Albert Ghiorso |

| Thermal properties | |

| Melting Point [Celsius scale] | 1050 |

| Boiling Point [Celsius scale] | — |

| Thermal Conductivity [W/m K] | 10 |

| Specific Heat [J/g K] | — |

| Heat of Fusion [kJ/mol] | — |

| Heat of Vaporization [kJ/mol] | — |

See also: Properties of Berkelium

Atomic Mass of Berkelium

Atomic mass of Berkelium is 247 u.

Note that, each element may contain more isotopes, therefore this resulting atomic mass is calculated from naturally-occuring isotopes and their abundance.

The unit of measure for mass is the atomic mass unit (amu). One atomic mass unit is equal to 1.66 x 10-24 grams. One unified atomic mass unit is approximately the mass of one nucleon (either a single proton or neutron) and is numerically equivalent to 1 g/mol.

For 12C, the atomic mass is exactly 12u since the atomic mass unit is defined from it. The isotopic mass usually differs for other isotopes and is usually within 0.1 u of the mass number. For example, 63Cu (29 protons and 34 neutrons) has a mass number of 63, and an isotopic mass in its nuclear ground state is 62.91367 u.

There are two reasons for the difference between mass number and isotopic mass, known as the mass defect:

- The neutron is slightly heavier than the proton. This increases the mass of nuclei with more neutrons than protons relative to the atomic mass unit scale based on 12C with equal numbers of protons and neutrons.

- The nuclear binding energy varies between nuclei. A nucleus with greater binding energy has lower total energy, and therefore a lower mass according to Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence relation E = mc2. For 63Cu, the atomic mass is less than 63, so this must be the dominant factor.

See also: Mass Number

Density of Berkelium

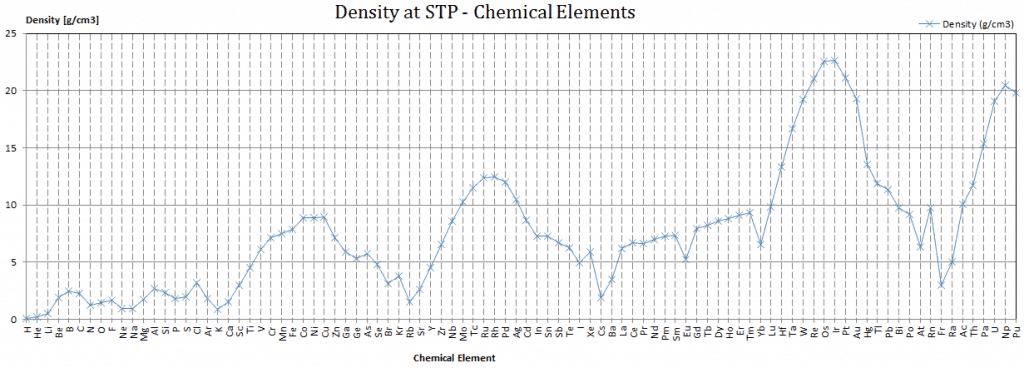

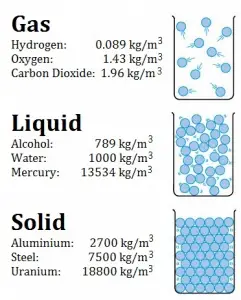

Density of Berkelium is 14.78g/cm3.

Typical densities of various substances at atmospheric pressure.

Density is defined as the mass per unit volume. It is an intensive property, which is mathematically defined as mass divided by volume:

ρ = m/V

In other words, the density (ρ) of a substance is the total mass (m) of that substance divided by the total volume (V) occupied by that substance. The standard SI unit is kilograms per cubic meter (kg/m3). The Standard English unit is pounds mass per cubic foot (lbm/ft3).

See also: What is Density

See also: Densest Materials of the Earth

Electron Affinity and Electronegativity of Berkelium

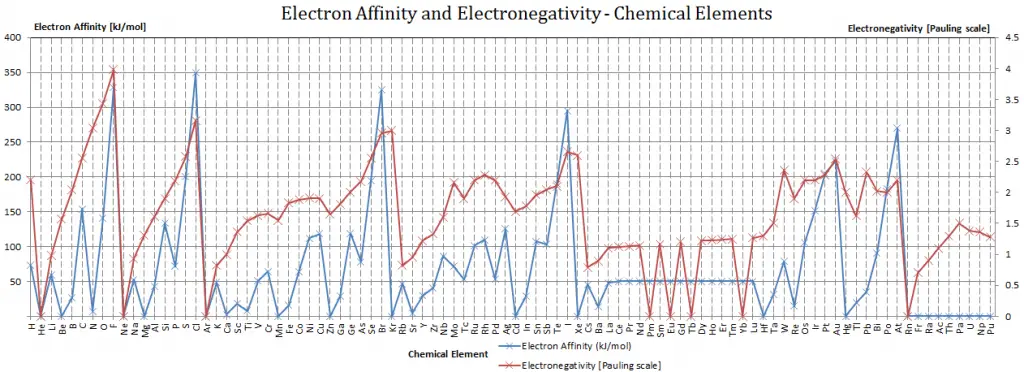

Electron Affinity of Berkelium is — kJ/mol.

Electronegativity of Berkelium is 1.3.

Electron Affinity

In chemistry and atomic physics, the electron affinity of an atom or molecule is defined as:

the change in energy (in kJ/mole) of a neutral atom or molecule (in the gaseous phase) when an electron is added to the atom to form a negative ion.

X + e– → X– + energy Affinity = – ∆H

In other words, it can be expressed as the neutral atom’s likelihood of gaining an electron. Note that ionization energies measure the tendency of a neutral atom to resist the loss of electrons. Electron affinities are more difficult to measure than ionization energies.

An atom of Berkelium in the gas phase, for example, gives off energy when it gains an electron to form an ion of Berkelium.

Bk + e– → Bk– – ∆H = Affinity = — kJ/mol

To use electron affinities properly, it is essential to keep track of signs. When an electron is added to a neutral atom, energy is released. This affinity is known as the first electron affinity, and these energies are negative. By convention, the negative sign shows a release of energy. However, more energy is required to add an electron to a negative ion which overwhelms any release of energy from the electron attachment process. This affinity is known as the second electron affinity, and these energies are positive.

Affinities of Nonmetals vs. Affinities of Metals

- Metals: Metals like to lose valence electrons to form cations to have a fully stable shell. The electron affinity of metals is lower than that of nonmetals. Mercury most weakly attracts an extra electron.

- Nonmetals: Generally, nonmetals have more positive electron affinity than metals. Nonmetals like to gain electrons to form anions to have a fully stable electron shell. Chlorine most strongly attracts extra electrons. The electron affinities of the noble gases have not been conclusively measured, so they may or may not have slightly negative values.

Electronegativity

Electronegativity, symbol χ, is a chemical property that describes the tendency of an atom to attract electrons towards this atom. For this purpose, a dimensionless quantity, the Pauling scale, symbol χ, is the most commonly used.

The electronegativity of Berkelium is:

χ = 1.3

In general, an atom’s electronegativity is affected by both its atomic number and the distance at which its valence electrons reside from the charged nucleus. The higher the associated electronegativity number, the more an element or compound attracts electrons towards it.

The most electronegative atom, fluorine, is assigned a value of 4.0, and values range down to cesium and francium, which are the least electronegative at 0.7.

First Ionization Energy of Berkelium

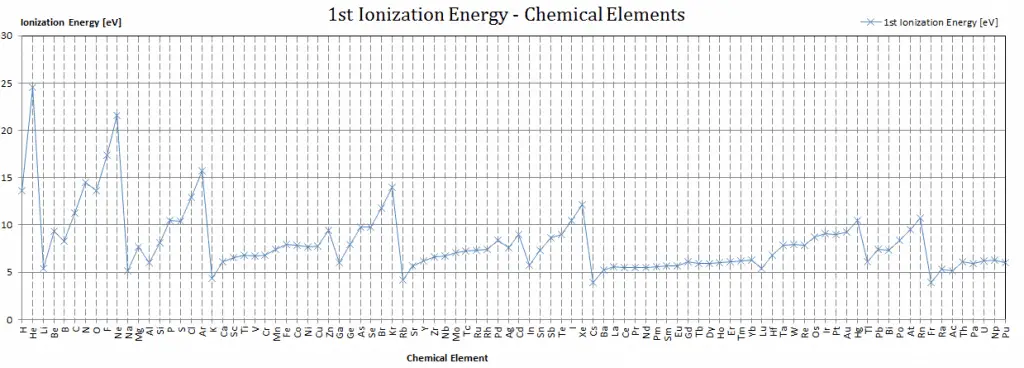

First Ionization Energy of Berkelium is 6.23 eV.

Ionization energy, also called ionization potential, is the energy necessary to remove an electron from the neutral atom.

X + energy → X+ + e−

where X is any atom or molecule capable of being ionized, X+ is that atom or molecule with an electron removed (positive ion), and e− is the removed electron.

A Berkelium atom, for example, requires the following ionization energy to remove the outermost electron.

Bk + IE → Bk+ + e− IE = 6.23 eV

The ionization energy associated with removal of the first electron is most commonly used. The nth ionization energy refers to the amount of energy required to remove an electron from the species with a charge of (n-1).

1st ionization energy

X → X+ + e−

2nd ionization energy

X+ → X2+ + e−

3rd ionization energy

X2+ → X3+ + e−

Ionization Energy for different Elements

There is ionization energy for each successive electron removed. The electrons that circle the nucleus move in fairly well-defined orbits. Some of these electrons are more tightly bound in the atom than others. For example, only 7.38 eV is required to remove the outermost electron from a lead atom, while 88,000 eV is required to remove the innermost electron. Helps to understand the reactivity of elements (especially metals, which lose electrons).

In general, the ionization energy increases moving up a group and moving left to the right across a period. Moreover:

- Ionization energy is lowest for the alkali metals, which have a single electron outside a closed shell.

- Ionization energy increases across a row on the periodic maximum for the noble gases which have closed shells.

For example, sodium requires only 496 kJ/mol or 5.14 eV/atom to ionize it. On the other hand, neon, the noble gas, immediately preceding it in the periodic table, requires 2081 kJ/mol or 21.56 eV/atom.

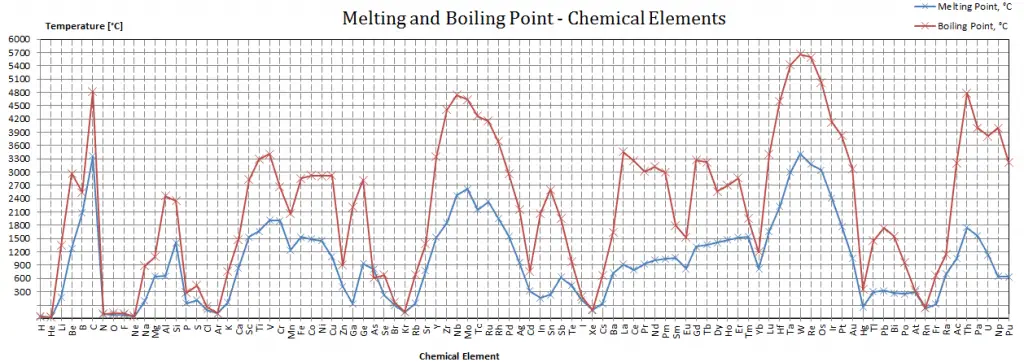

Berkelium – Melting Point and Boiling Point

Melting point of Berkelium is 1050°C.

Boiling point of Berkelium is –°C.

Note that these points are associated with the standard atmospheric pressure.

Boiling Point – Saturation

In thermodynamics, saturation defines a condition in which a mixture of vapor and liquid can exist together at a given temperature and pressure. The temperature at which vaporization (boiling) starts to occur for a given pressure is called the saturation temperature or boiling point. The pressure at which vaporization (boiling) starts to occur for a given temperature is called the saturation pressure. When considered as the temperature of the reverse change from vapor to liquid, it is referred to as the condensation point.

Melting Point – Saturation

In thermodynamics, the melting point defines a condition in which the solid and liquid can exist in equilibrium. Adding heat will convert the solid into a liquid with no temperature change. The melting point of a substance depends on pressure and is usually specified at standard pressure. When considered as the temperature of the reverse change from liquid to solid, it is referred to as the freezing point or crystallization point.

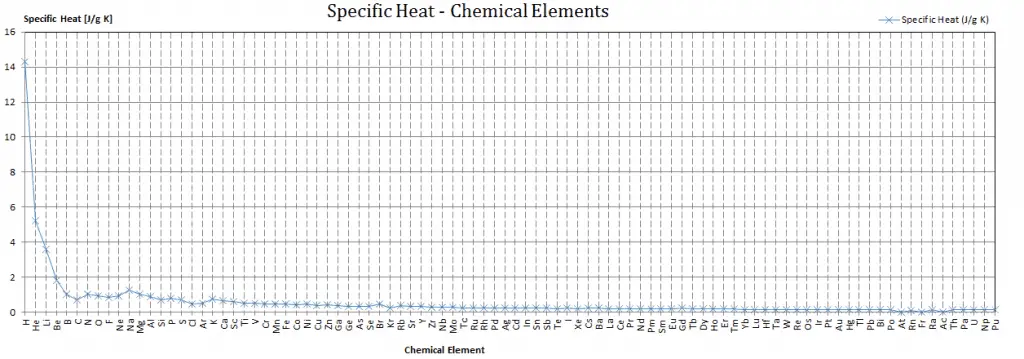

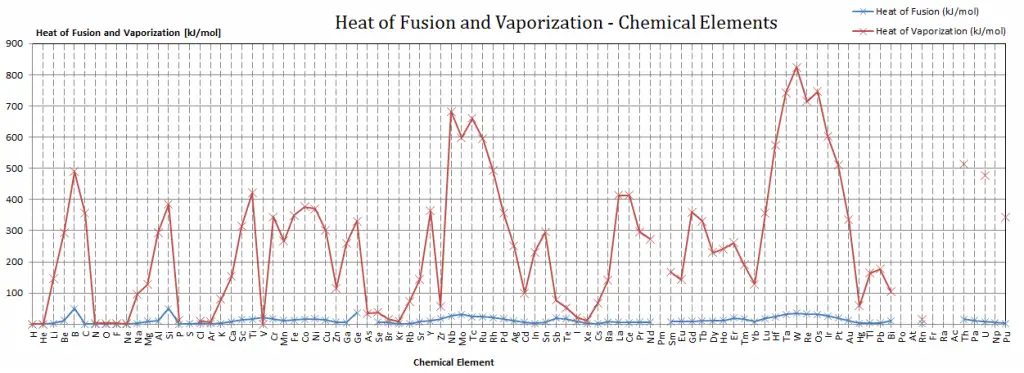

Berkelium – Specific Heat, Latent Heat of Fusion, Latent Heat of Vaporization

Specific heat of Berkelium is — J/g K.

Latent Heat of Fusion of Berkelium is — kJ/mol.

Latent Heat of Vaporization of Berkelium is — kJ/mol.

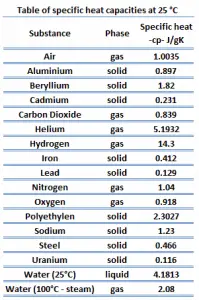

Specific Heat

Specific heat, or specific heat capacity, is a property related to internal energy that is very important in thermodynamics. The intensive properties cv and cp are defined for pure, simple compressible substances as partial derivatives of the internal energy u(T, v) and enthalpy h(T, p), respectively:

where the subscripts v and p denote the variables held fixed during differentiation. The properties cv and cp are referred to as specific heats(or heat capacities) because, under certain special conditions, they relate the temperature change of a system to the amount of energy added by heat transfer. Their SI units are J/kg K or J/mol K.

where the subscripts v and p denote the variables held fixed during differentiation. The properties cv and cp are referred to as specific heats(or heat capacities) because, under certain special conditions, they relate the temperature change of a system to the amount of energy added by heat transfer. Their SI units are J/kg K or J/mol K.

Different substances are affected to different magnitudes by the addition of heat. When a given amount of heat is added to different substances, their temperatures increase by different amounts.

Heat capacity is an extensive property of matter, meaning it is proportional to the size of the system. Heat capacity C has the unit of energy per degree or energy per kelvin. When expressing the same phenomenon as an intensive property, the heat capacity is divided by the amount of substance, mass, or volume. Thus the quantity is independent of the size or extent of the sample.

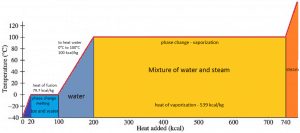

Latent Heat of Vaporization

In general, when a material changes phase from solid to liquid or from liquid to gas, a certain amount of energy is involved in this change of phase. In the case of liquid to gas phase change, this amount of energy is known as the enthalpy of vaporization (symbol ∆Hvap; unit: J), also known as the (latent) heat of vaporization or heat of evaporation. As an example, see the figure, which describes the phase transitions of water.

Latent heat is the amount of heat added to or removed from a substance to produce a change in phase. This energy breaks down the attractive intermolecular forces and must provide the energy necessary to expand the gas (the pΔV work). When latent heat is added, no temperature change occurs. The enthalpy of vaporization is a function of the pressure at which that transformation takes place.

Latent Heat of Fusion

In the case of solid to liquid phase change, the change in enthalpy required to change its state is known as the enthalpy of fusion (symbol ∆Hfus; unit: J), also known as the (latent) heat of fusion. Latent heat is the amount of heat added to or removed from a substance to produce a phase change. This energy breaks down the attractive intermolecular forces and also must provide the energy necessary to expand the system (the pΔV work).

The liquid phase has higher internal energy than the solid phase. This means energy must be supplied to a solid in order to melt it, and energy is released from a liquid when it freezes because the molecules in the liquid experience weaker intermolecular forces and so have higher potential energy (a kind of bond-dissociation energy for intermolecular forces).

The temperature at which the phase transition occurs is the melting point.

When latent heat is added, no temperature change occurs. The enthalpy of fusion is a function of the pressure at which that transformation takes place. By convention, the pressure is assumed to be 1 atm (101.325 kPa) unless otherwise specified.

Berkelium in Periodic Table

–

–

–