Reactor Physics

What is nuclear reactor physics?

Nuclear reactor physics is the field of physics that studies and deals with the applied study and engineering applications of neutron diffusion and fission chain reaction to induce a controlled fission rate in a nuclear reactor for energy production. The nuclear reactor theory is based on diffusion theory and reactor dynamics, which defines the “criticality” of the reactor.

Key Facts

- The study of neutron nuclear reactions and nuclear reactions, in general, is of paramount importance in the physics of nuclear reactors.

- Nuclear fission is a nuclear reaction or a decay process in which the heavy nucleus splits into smaller parts (lighter nuclei).

- In nuclear physics, the nuclear cross-section of a nucleus is commonly used to characterize the probability that a nuclear reaction will occur.

- Doppler broadening of the resonance capture cross-sections of the fertile material (e.g.,, 238U or 240Pu) caused by the thermal motion of target nuclei in the nuclear fuel is of the highest importance for reactor stability.

- If the multiplication factor for a multiplying system is equal to 1.0, the chain reaction will be self-sustaining.

- Neutron diffusion theory deals with the spatial migration of neutrons and helps to understand the relationships between reactor size, shape, and criticality. It is also used to determine the spatial flux distributions within power reactors.

- Nuclear reactor kinetics deals with transient neutron flux changes resulting from a departure from the critical state.

- Reactor dynamics is also referred to as reactor kinetics with feedbacks and with spatial effects.

- Basic reactor operation physics includes these topics: Reactor Startup (“criticality approach”), Control of the Reactor and Power Maneuvering, and Xenon Oscillations.

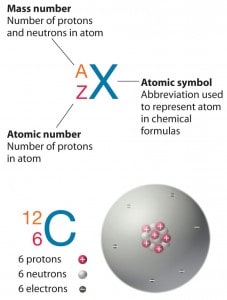

Atomic and Nuclear Physics

Source: chemwiki.ucdavis.edu

Knowledge of atomic and nuclear physics is essential to nuclear engineers who deal with nuclear reactors. It should be noted that atomic and nuclear physics is a very extensive branch of science. Nuclear reactor physics belongs to applied physics, drawing from particle physics or nuclear chemistry. These branches have common fundamentals. Atomic and nuclear physics describe fundamental particles (i.e., electrons, protons, neutrons), structure, properties, and behavior. These physical fundamentals consist of:

- Fundamental Particles

- Atomic and Nuclear Structure

- Mass and Energy

- Radiation

- Nuclear Stability

- Radioactive Decay

- Nuclear Reactions

- Binding Energy

See also: Atomic and Nuclear Physics

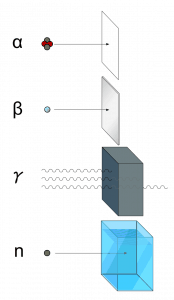

Interaction of Radiation with Matter

The design of all nuclear reactors and other nuclear systems depends fundamentally on how nuclear radiation interacts with matter. In a nuclear reactor, we typically encounter these types of radiation:

- Interactions of heavy charged particles

- Interactions of beta radiation

- Interactions of gamma rays

- Interactions of neutrons

- Reactor antineutrinos

See also: Interaction of Radiation with Matter

Neutron Diffusion Theory

Neutron diffusion theory is the branch of science that studies the behavior and application of neutrons within the nuclear core or in various environments. Diffusion theory provides a theoretical basis for neutron-physical computer simulation of nuclear cores. The term theoretical has to be emphasized.

It is necessary to predict how the neutrons will be distributed throughout the system to design a nuclear reactor properly. This, in general, is a difficult problem, for the neutrons move in a reactor in complicated paths as a result of repeated collisions. To a first approximation, the overall effect of these collisions is that the neutrons undergo a kind of diffusion in the reactor medium, much like the diffusion of one gas in another. This approximation allows solving such problems using the diffusion equation.

Nuclear Reactor Theory

The nuclear reactor theory is based on diffusion theory and reactor dynamics, which defines the “criticality” of the reactor. Using the term “criticality” may seem counter-intuitive as a way to describe normalcy. The word often describes situations with the potential for disaster. Nevertheless, in the context of nuclear power, “critical” indicates that a reactor is operating safely, and the neutron flux and power level are stable. In a critical reactor, there is an exact balance between the number of neutrons produced in fission and the number lost, either by absorption in the reactor or by leaking from its surface. Nuclear reactor theory solves the central problem in the design of a reactor: calculation of the size and composition (nuclear fuel) of the system required to maintain this balance.

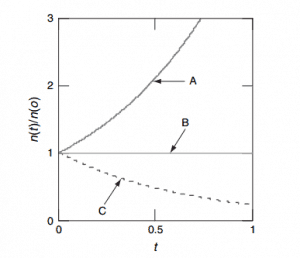

Reactor Kinetics – Zero Power Physics

The nuclear reactor theory is concerned with critical nuclear reactors operating at constant power. But the reactor must not always be in a critical state. The reactor must be noncritical (supercritical or subcritical) to change the reactor power. The study of the behavior of neuron populations in a noncritical reactor is called reactor kinetics. This theory introduces a new unit – reactivity – of a nuclear reactor. The reactivity characterizes the deflection of the reactor from the critical state.

It should be noted this theory can be used for a reactor at low power levels, hence “zero power criticality” (i.e., a reactor without reactivity feedbacks, 10E-8% – 1% of rated power). The first periods of a reactor operation (reactor startup and power maneuvering at low power levels) are well described by this theory. Once the reactor core heats up (thermal power outweighs decay power), reactivity feedbacks change the dynamics of the reactor.

Reactor operation – Full Power Physics

Source: wikipedia.org

This branch of nuclear engineering is very specific and dependent on reactor type. This article focuses on the most common type of reactor – Pressurized Water Reactors. PWRs have much in common with Boiling Water Reactors, but the operation of the reactors is not the same. On the other hand, for example, fast neutron reactors have completely different physics than PWRs and BWRs.

The degree of criticality at high power levels (~1% – 100% of rated power) is influenced by many variables. The most important are summarized below.

- Nuclear Fuel and Fuel Loading Pattern

- Fuel Depletion

- Neutron Leakage

- Control Rods and Chemical Shim

- Reactivity Feedbacks

- Burnable Absorbers

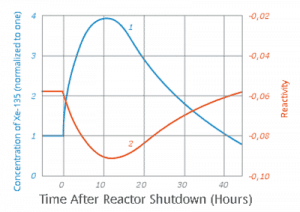

- Xenon and Samarium Poisoning

Basic reactor operation physics includes these operation states:

- Reactor Startup (“going critical”)

- Control of the Reactor and Power Maneuvering.

- Axial Offset Control.

- Xenon Oscillations

- Reactor Shutdown.

- Emergency Shutdown – SCRAM

Thermohydraulics of Nuclear Core

Heat removal from nuclear reactors is also a key issue of reactor physics. For a reactor to operate in a steady state, with an internal power distribution that is independent of time, all of the heat released in the system must be removed as fast as it is produced. This is accomplished by passing a coolant (water in case of PWRs or BWRs) through the core and other regions where heat is generated.

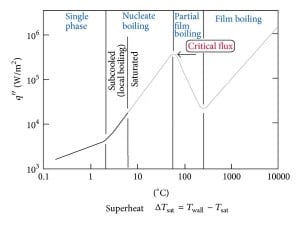

The thermohydraulics deals with thermal behavior (heat generation, heat removal) and the nuclear core’s hydraulic behavior (Delta P, cross-flow issue, flow pattern). The nature and operation of this coolant system are some of the most important considerations in designing a nuclear reactor. In the PWR reactors, some phenomena must be avoided. Namely, DNB (Departure from Nucleate Boiling) and coolant saturation are very dangerous phenomena.

The behavior of Fuel Rod

The thermal and mechanical behavior of nuclear fuel constitutes one of three key core design disciplines. Nuclear fuel is operated under inhospitable conditions (thermal, radiation, mechanical) and must withstand more than normal conditions operation. For example, temperatures in the center of fuel pellets reach more than 1000°C (1832°F), accompanied by fission-gas releases. The behavior of nuclear fuel is associated with many phenomena. The most important are summarized below.

- Fuel swelling

- Fuel densification

- Thermal expansion

- Fuel relocation

- High Burnup Structure

- Pellet-Cladding Interaction

- Pellet-Coolant Interaction

- Fission-Gas Releases

Applied Core Physics

Applied core physics is the branch of science that deals with studying the behavior of a specific reactor core, which depends on a specific refueling schema. As was written, during refueling, every 12 to 18 months, some of the fuel – usually one-third or one-quarter of the core – is removed to the spent fuel pool. At the same time, the remainder is rearranged to a location in the core better suited to its remaining level of enrichment. The removed fuel (one-third or one-quarter of the core, i.e., 40 assemblies) must be replaced by fresh fuel assemblies.

For every fuel reload, plant operators shall determine main core characteristics (e.g.,, power distribution). Plant operators shall verify that these main core characteristics do not violate the initial and boundary conditions used in the Safety Analyses Report (SAR).

Full-scale physical computing of reactor core includes these types of computations:

- Core Design computing

- Fuel cross-section computing. Neutron cross-sections must be calculated for new fuel assemblies, usually in two-Dimensional models of the fuel lattice.

- Loading Pattern search. The best arrangement of new fuel assemblies and used fuel assemblies are searched for in the core design from the viewpoints of safety and economy.

- Fuel Cycle depletion. Each proposed fuel cycle’s behavior and key safety parameters (power distribution, reactor kinetics parameters, control rods efficiency, etc.) must be analyzed for the entire duration of the proposed cycle.

- Reload Safety Assessment

- Neutron-physical computing

- Thermal-hydraulic computing

- Fuel rod behavior computing

Safety of Nuclear Reactors

Meaning of ‘(nuclear) safety’

‘Safety’ is the achievement of proper operating conditions, prevention of accidents, and mitigation of accident consequences, resulting in the protection of workers, the public, and the environment from undue radiation hazards.

Nuclear safety is a very broad branch of nuclear engineering. The three primary objectives of nuclear reactor safety systems as defined by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission are to shut down the reactor, maintain it in a shutdown condition, and prevent the release of radioactive material. Appropriate redundant and diverse safety systems are installed to ensure the safety of the nuclear reactor.

Most nuclear power plants introduce a ‘defense-in-depth’ approach to achieve maximum safety. This approach is constituted of multiple safety systems supplementing the natural features of the reactor core.