If the radiation source is inside our body, we say it is internal exposure. The intake of radioactive material can occur through various pathways such as ingesting radioactive contamination in food or liquids, inhalation of radioactive gases, or through intact or wounded skin. Most radionuclides will give you much more radiation dose if they can somehow enter your body than they would if they remained outside. For internal doses, we first should distinguish between intake and uptake. Intake means what a person takes in, and uptake means what a person keeps.

When a radioactive compound enters the body, the activity will decrease with time due to radioactive decay and biological clearance. The decrease varies from one radioactive compound to another. For this purpose, the biological half-life is defined in radiation protection.

The biological half-life is the time taken for the amount of a particular element in the body to decrease to half of its initial value due to elimination by biological processes alone when the removal rate is roughly exponential. The biological half-life depends on the rate at which the body normally uses a particular compound of an element. Radioactive isotopes that were ingested or taken in through other pathways will gradually be removed from the body via bowels, kidneys, respiration, and perspiration. This means that a radioactive substance can be expelled before it has had the chance to decay.

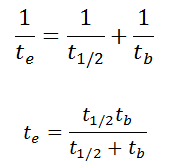

As a result, the biological half-life significantly influences the effective half-life and the overall dose from internal contamination. If a radioactive compound with a radioactive half-life (t1/2) is cleared from the body with a biological half-life tb, the effective half-life (te) is given by the expression:

As can be seen, the biological mechanisms always decrease the overall dose from internal contamination. Moreover, if t1/2 is large compared to tb, the effective half-life is approximately the same as tb.

For example, tritium has a biological half-life of about 10 days, while the radioactive half-life is about 12 years. On the other hand, radionuclides with very short radioactive half-lives also have very short effective half-lives. These radionuclides will deliver, for all practical purposes, the total radiation dose within the first few days or weeks after intake.

For tritium, the annual limit intake (ALI) is 1 x 109 Bq. If you take 1 x 109 Bq of tritium, you will receive a whole-body dose of 20 mSv. The committed effective dose, E(t), is 20 mSv. It does not depend on whether a person intakes this amount of activity in a short or long time. In every case, this person gets the same whole-body dose of 20 mSv.

Committed Effective Dose

In radiation protection, the committed dose is a dose quantity that measures the stochastic health risk due to an intake of radioactive material into the human body. The committed dose is given the symbol E(t), where t is the integration time in years following the intake. The SI unit of E(t) is the sievert (Sv) or but rem (roentgen equivalent man) is still commonly used (1 Sv = 100 rem). Unit of sievert was named after the Swedish scientist Rolf Sievert, who did a lot of the early work on dosimetry in radiation therapy.

Committed dose allows us to determine the biological consequences of irradiation caused by radioactive material inside our bodies. A committed dose of 1 Sv from an internal source represents the same effective risk as the same amount of effective dose of 1 Sv applied uniformly to the whole body from an external source.

The ICRP defines two-dose quantities for individual committed doses.

Committed Effective Dose

According to the ICRP, the committed effective dose, E(t), is defined as:

“The sum of the products of the committed organ or tissue equivalent doses and the appropriate tissue weighting factors (wT), where t is the integration time in years following the intake. The commitment period is taken to be 50 years for adults, and to age 70 years for children.”

Committed Equivalent Dose

According to the ICRP, the committed equivalent dose, HT(t), is defined as:

“The time integral of the equivalent dose rate in a particular tissue or organ that will be received by an individual following intake of radioactive material into the body by a Reference Person, where t is the integration time in years.”

Special Reference: ICRP, 2007. The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP Publication 103. Ann. ICRP 37 (2-4).

Annual Limit on Intake – ALI

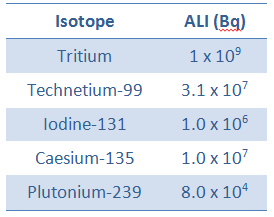

In assessing committed effective doses for workers, intakes of radioactive material are controlled by the Annual Limit on Intake (ALI) defined by the ICRP and expressed in units of activity (becquerels or curies).

The ALI was defined in by the ICRP in Publication 60 (ICRP, 1991b, paragraph S30) as:

“the activity intake (Bq) of a radionuclide which would lead to an effective dose corresponding to the annual limit Elimit;w, under the expectation that the worker is exposed to only this radionuclide.”

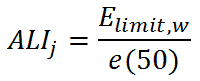

The ALI of radionuclide j is then:

where e(50) is the corresponding reference committed effective dose coefficient in (Sv/Bq). This dose coefficient, e(T), is determined by the radiotoxicity of a nuclide, and it accounts for radiation and tissue weighting factors and metabolic and biokinetic information.

See also: ICRP, 1994. Dose Coefficients for Intakes of Radionuclides by Workers. ICRP Publication 68. Ann. ICRP 24 (4).

The Commission recommended in Publication 60 that the ALI should be based on the dose limit of Elimit;w = 0.020 Sv in a year, with no time averaging. For members of the public Elimit;w = 0.001 Sv is the recommended value.

As an example, let’s assume an intake of radioactive tritium. For tritium, the annual limit intake (ALI) is 1 x 109 Bq. If you take 1 x 109 Bq of tritium, you will receive a whole-body dose of 20 mSv. Note that the biological half-life is about 10 days, while the radioactive half-life is about 12 years. Instead of years, it takes a couple of months until the tritium has been pretty well eliminated. The committed effective dose, E(t), is 20 mSv. It does not depend on whether a person intakes this amount of activity in a short or long time. In every case, this person gets the same whole-body dose of 20 mSv.

For 131I, ICRP has calculated that if you inhale 1 x 106 Bq (ALI for 131I), you will receive a thyroid dose of HT = 400 mSv (and a weighted whole-body dose of 20 mSv).

Derived Air Concentration – DAC

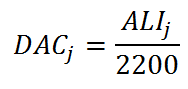

Concentrations of radioactive materials in the air are limited by the Derived Air Concentration (DAC), which is derived from the ALI. The DAC is the activity concentration in air in units of Bq/m3 of the radionuclide considered, which would lead to an intake of an ALI (Bq) assuming a gender-averaged breathing rate of 1.1 m3/h and an annual working time of 2000 h (an annual air intake of 2200 m3).

The DAC was defined in by the ICRP in Publication 60 (ICRP, 1991b, paragraph S30) as:

“Derived air concentration equals the annual limit on intake, ALI, (of a radionuclide) divided by the volume of air inhaled by a Reference Person in a working year (i.e., 2.2×103 m3). The unit of DAC is Bq/m3.”

Special Reference: ICRP, 2007. The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP Publication 103. Ann. ICRP 37 (2-4).

Therefore, if we divide the ALI by 2200 m3, we will get the DAC in Bq/m3. For example, the ALI of iodine-131 is 1 x 106 Bq. The corresponding DAC will be 1 000 000/2400 = 417 Bq/m3.

The DAC of radionuclide j is given by:

If a worker breathes air containing radioactive material at a concentration of 1 DAC for one hour, then the worker has been exposed to 1 DAC.hr.

See also: Airborne Contamination

Occupational Exposure – Effective Dose

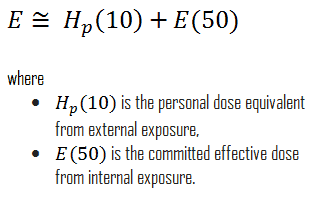

In most situations of occupational exposure, the effective dose, E, can be derived from operational quantities using the following formula:

The committed dose is a dose quantity that measures the stochastic health risk due to an intake of radioactive material into the human body. Since the operational dose limit of 20 mSv applies to the sum of the internal and external exposures, if a worker has some external dose, the ALI must be modified or offset to account for the external dose. For example, assume the worker has 10 mSv from external radiation sources, and only 10 more mSv are allowed from internal radiation before the worker reaches the occupational whole body limit.

See also: Dose Limits