Definition of Heat

While internal energy refers to the total energy of all the molecules within the object, heat is the amount of energy flowing spontaneously from one body to another due to their temperature difference. Heat is a form of energy, but it is energy in transit. Heat is not a property of a system. However, the transfer of energy as heat occurs at the molecular level due to a temperature difference.

While internal energy refers to the total energy of all the molecules within the object, heat is the amount of energy flowing spontaneously from one body to another due to their temperature difference. Heat is a form of energy, but it is energy in transit. Heat is not a property of a system. However, the transfer of energy as heat occurs at the molecular level due to a temperature difference.

Consider a block of metal at high temperature that consists of atoms oscillating intensely around their average positions. At low temperatures, the atoms continue to oscillate but with less intensity. If a hotter block of metal is put in contact with a cooler block, the intensely oscillating atoms at the edge of the hotter block give off their kinetic energy to the less oscillating atoms at the edge of the cool block. In this case, there is energy transfer between these two blocks, and heat flows from the hotter to the cooler block by these random vibrations.

As with work, the amount of heat transferred depends upon the path and not simply on the initial and final conditions of the system. There are many ways to take the gas from state i to state f.

Also, as with work, it is important to distinguish between heat added to a system from its surroundings and heat removed from a system to its surroundings. Q is positive for heat added to the system, so Q is negative if heat leaves the system. Because W in the equation is the work done by the system, then if work is done on the system, W will be negative, and Eint will increase.

The symbol q is sometimes used to indicate the heat added to or removed from a system per unit mass. It equals the total heat (Q) added or removed divided by the mass (m).

Distinguishing Temperature, Heat, and Internal Energy

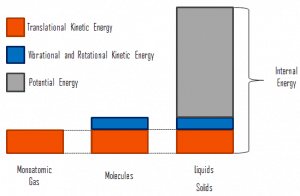

Using the kinetic theory, a clear distinction between these three properties can be made.

- Temperature is related to the kinetic energies of the molecules of material, and it is the average kinetic energy of individual molecules.

- Internal energy refers to the total energy of all the molecules within the object. Therefore, it is an extensive property when two equal-mass hot ingots of steel may have the same temperature, but two of them have twice as much internal energy as one does.

- Finally, heat is the amount of energy flowing spontaneously from one body to another due to their temperature difference.

When a temperature difference exists, it must be added, and heat flows spontaneously from the warmer system to the colder system. Thus, if a 5 kg cube of steel at 100°C is placed in contact with a 500 kg cube of steel at 20°C, heat flows from the cube at 300°C to the cube at 20°C even though the internal energy of the 20°C cube is much greater because there is so much more of it.

A particularly important concept is thermodynamic equilibrium. In general, when two objects are brought into thermal contact, heat will flow between them until they come into equilibrium with each other.

Example – Evaporation of water at atmospheric pressure

Calculate heat required to evaporate 1 kg of water at the atmospheric pressure (p = 1.0133 bar) and the temperature of 100°C.

Solution:

Since these parameters correspond to the saturated liquid state, only latent heat of vaporization of 1 kg of water is required. From steam tables, the latent heat of vaporization is L = 2257 kJ/kg. Therefore the heat required is equal to:

ΔH = 2257 kJ

Note that the initial specific enthalpy h1 = 419 kJ/kg, whereas the final specific enthalpy will be h2 = 2676 kJ/kg. The specific enthalpy of low-pressure dry steam is very similar to the specific enthalpy of high-pressure dry steam, despite the fact they have different temperatures.

Example – Evaporation of water at high pressure

Calculate heat required to evaporate 1 kg of feedwater at the pressure of 6 MPa (p = 60 bar) and the temperature of 275.6°C (saturation temperature).

Solution:

Since these parameters correspond to the saturated liquid state, only latent heat of vaporization of 1 kg of water is required. From steam tables, the latent heat of vaporization is L = 1571 kJ/kg. Therefore the heat required is equal to:

ΔH = 1571 kJ

Note that the initial specific enthalpy h1 = 1214 kJ/kg, whereas the final specific enthalpy will be h2 = 2785 kJ/kg.