Article Summary & FAQs

What is head loss or pressure loss?

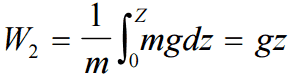

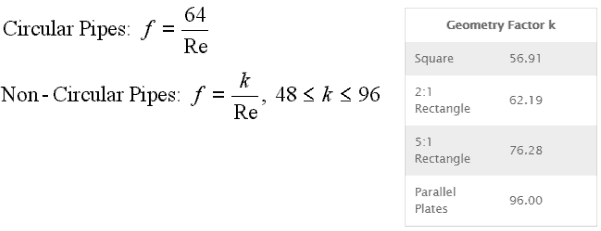

In fluid flow, head loss or pressure loss reduces the total head (sum of the potential head, velocity head, and pressure head) of a fluid caused by the friction present in the fluid’s motion.

Key Facts

- Head loss of the hydraulic system is divided into two main categories:

- Major Head Loss – due to friction in straight pipes

- Minor Head Loss – due to components as valves, bends…

- Major head losses are a function of:

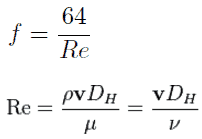

- flow regime (i.e., Reynolds number)

- flow velocity

- pipe diameter and its length

- friction factor (flow regime (i.e., Reynolds number), relative roughness)

- Minor head losses are a function of:

- flow regime (i.e., Reynolds number)

- flow velocity

- the geometry of a given component

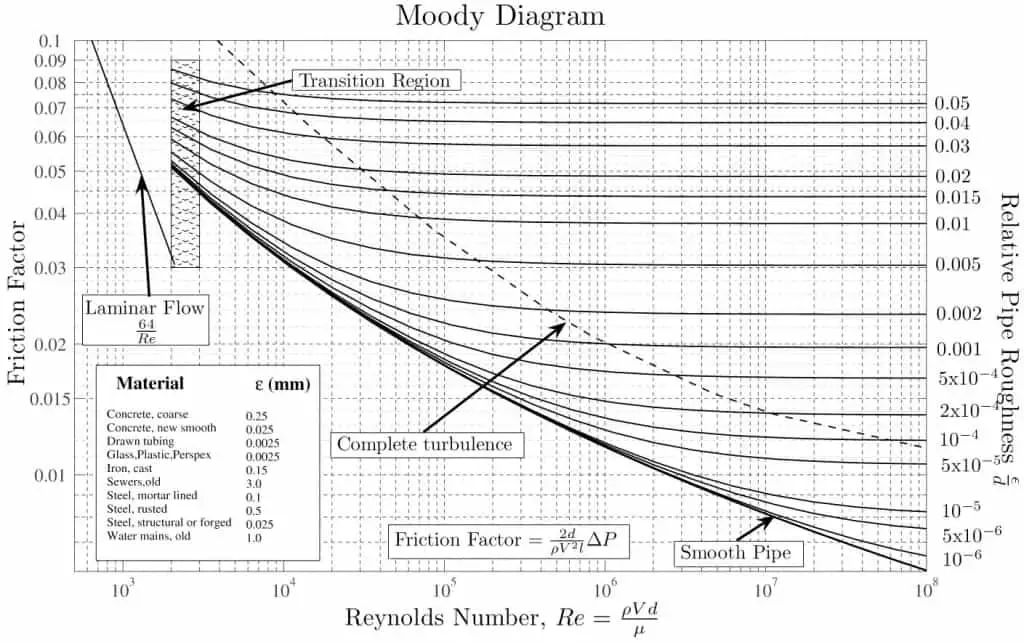

- Darcy’s equation can be used to calculate major losses. The friction factor for fluid flow can be determined using a Moody chart.

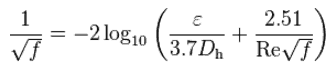

- The Darcy friction factor is a dimensionless quantity used in the Darcy–Weisbach equation to describe frictional losses in pipe or duct and open-channel flow. This is also called the Darcy–Weisbach friction factor, resistance coefficient, or simply friction factor.

- A special form of Darcy’s equation can be used to calculate minor losses. The minor losses are roughly proportional to the square of the flow rate, and therefore they can be easily integrated into the Darcy-Weisbach equation through resistance coefficient K.

Head Loss – Pressure Loss

In the practical analysis of piping systems, the quantity of most importance is the pressure loss due to viscous effects along the length of the system, as well as additional pressure losses arising from other technological equipment like valves, elbows, piping entrances, fittings, and tees.

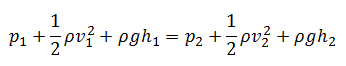

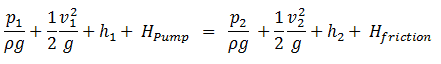

At first, an extended Bernoulli’s equation must be introduced. This equation permits account of viscosity to be included empirically and quantify this with a physical parameter known as head loss.

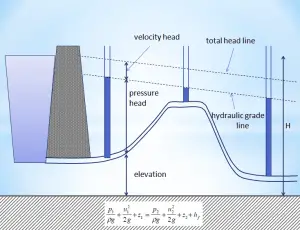

The head loss (or the pressure loss) represents the reduction in the total head or pressure (sum of elevation head, velocity head, and pressure head) of the fluid as it flows through a hydraulic system. The head loss also represents the energy used in overcoming friction caused by the pipe walls and other technological equipment. Head loss is unavoidable in real moving fluids. It is present because of the friction between adjacent fluid particles moving relative to one another (especially in turbulent flow).

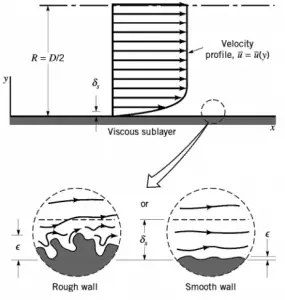

The head loss that occurs in pipes is dependent on the flow velocity, pipe diameter, and length, and a friction factor based on the roughness of the pipe and the Reynolds number of the flow. Although the head loss represents a loss of energy, it does not represent a loss of total energy of the fluid. The total energy of the fluid is conserved as a consequence of the law of conservation of energy. In reality, the head loss due to friction results in an equivalent increase in the fluid’s internal energy (temperature increases).

Most methods for evaluating head loss due to friction are based almost exclusively on experimental evidence. This will be discussed in the following sections.

Classification of Head Loss

The head loss of a pipe, tube, or duct system, is the same as that produced in a straight pipe or duct whose length is equal to the pipes of the original systems plus the sum of the equivalent lengths of all the components in the system.

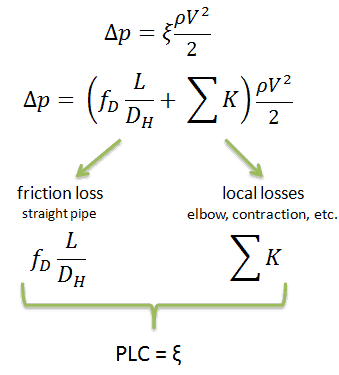

As can be seen, the head loss of the piping system is divided into two main categories, “major losses” associated with energy loss per length of pipe, and “minor losses” associated with bends, fittings, valves, etc.

- Major Head Loss – due to friction in pipes and ducts.

- Minor Head Loss – due to components as valves, fittings, bends, and tees.

The head loss can be then expressed as:

hloss = Σ hmajor_losses + Σ hminor_losses

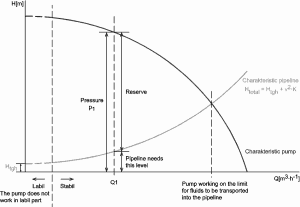

Why is head loss very important?

As can be seen from the picture, the head loss is formed key characteristic of any hydraulic system. In systems in which some certain flowrate must be maintained (e.g.,, to provide sufficient cooling or heat transfer from a reactor core), the equilibrium of the head loss and the head added by a pump determine the flow rate through the system.

Major Head Loss – Frictional Loss

See also: Major Head Loss – Frictional Losses

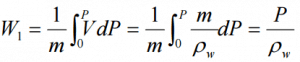

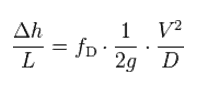

Major losses, which are associated with frictional energy loss per length of the pipe, depends on the flow velocity, pipe length, pipe diameter, and a friction factor based on the roughness of the pipe and whether the flow is laminar or turbulent (i.e., the Reynolds number of the flow).

Although the head loss represents a loss of energy, it does not represent a loss of total energy of the fluid. The total energy of the fluid is conserved as a consequence of the law of conservation of energy. In reality, the head loss due to friction results in an equivalent increase in the fluid’s internal energy (temperature increases).

By observation, the major head loss is roughly proportional to the square of the flow rate in most engineering flows (fully developed, turbulent pipe flow).

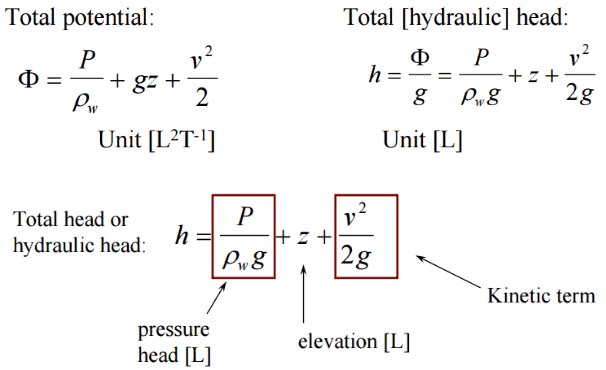

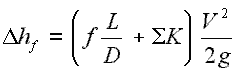

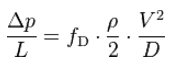

The most common equation used to calculate major head losses in a tube or duct is the Darcy–Weisbach equation (head loss form).

where:

- Δh = the head loss due to friction (m)

- fD = the Darcy friction factor (unitless)

- L = the pipe length (m)

- D = the hydraulic diameter of the pipe D (m)

- g = the gravitational constant (m/s2)

- V = the mean flow velocity V (m/s)

Evaluating the Darcy-Weisbach equation provides insight into factors affecting head loss in a pipeline.

- Consider that the length of the pipe or channel is doubled, the resulting frictional head loss will double.

- At constant flow rate and pipe length, the head loss is inversely proportional to the 4th power of diameter (for laminar flow). Thus, reducing the pipe diameter by half increases the head loss by a factor of 16. This is a significant increase in head loss and shows why larger diameter pipes lead to much smaller pumping power requirements.

- Since the head loss is roughly proportional to the square of the flow rate, then if the flow rate is doubled, the head loss increases by a factor of four.

- The head loss is reduced by half (for laminar flow) when the fluid’s viscosity is reduced by half.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4681366

Except for the Darcy friction factor, each of these terms (the flow velocity, the hydraulic diameter, the length of a pipe) can be easily measured. The Darcy friction factor takes the fluid properties of density and viscosity into account, along with the pipe roughness. This factor may be evaluated using various empirical relations or read from published charts (e.g.,, Moody chart).

Minor Head Loss – Local Pressure Loss

See also: Minor Head Loss – Local Pressure Loss

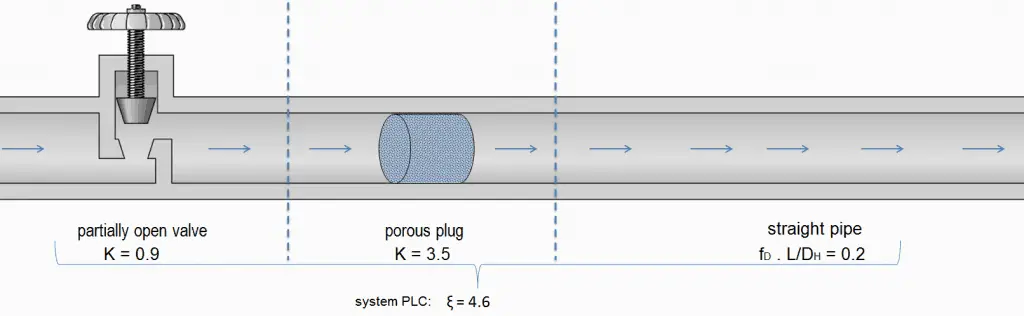

In industry, any pipe system contains different technological elements as bends, fittings, valves, or heated channels. These additional components add to the overall head loss of the system. Such losses are generally termed minor losses, although they often account for a major portion of the head loss. For relatively short pipe systems, with a relatively large number of bends and fittings, minor losses can easily exceed major losses (especially with a partially closed valve that can cause a greater pressure loss than a long pipe when a valve is closed or nearly closed, the minor loss is infinite).

The minor losses are commonly measured experimentally. The data, especially for valves, are somewhat dependent upon the particular manufacturer’s design.

Generally, most methods that are used in the industry define a coefficient K as a value for a certain technological component.

Like pipe friction, the minor losses are roughly proportional to the square of the flow rate, and therefore they can be easily integrated into the Darcy-Weisbach equation. K is the sum of all of the loss coefficients in the length of pipe, each contributing to the overall head loss.

The following methods are of practical importance in local pressure loss calculations:

- Equivalent Length Method

- K-Method – Resistance Coefficient Method

- 2K-Method

- 3K-Method

See also: Minor Head Loss – Local Pressure Loss

Head Loss of Two-phase Fluid Flow

See also: Two-phase Pressure Drop

In contrast, to single-phase pressure drops, calculation and prediction of two-phase pressure drops is a much more sophisticated problem, and leading methods differ significantly. Experimental data indicates that the frictional pressure drop in the two-phase flow (e.g.,, in a boiling channel) is substantially higher than for a single-phase flow with the same length and mass flow rate. Explanations include an increased surface roughness due to bubble formation on the heated surface and increased flow velocities.