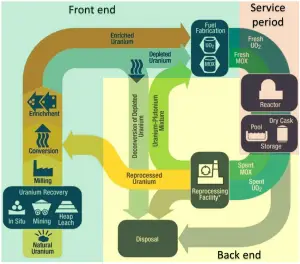

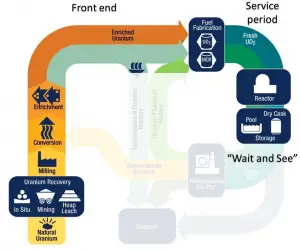

The nuclear fuel cycle is a process chain consisting of various stages. The nuclear fuel cycle starts with the mining of uranium and ends with the disposal of nuclear waste. The stages form a true cycle with reprocessing used fuel as an option for nuclear energy. In general, the nuclear fuel cycle consists of steps in the front end (the preparation of the fuel), steps in the service period (fuel burnup), and steps in the back end (reprocessing or disposal of spent nuclear fuel).

- The front end of the nuclear fuel cycle. The front end of the nuclear fuel cycle starts with the mining of uranium in the mines and ends with the delivery of the enriched uranium to the nuclear fuel assembly producer. Therefore, the front end of the fuel cycle consists of:

- Uranium mining, milling and mill tailings,

- Conversion

- Fuel enrichment

- Fabrication of fuel assemblies

- Service Period. The service period includes transport of fuel assemblies within a power plant, in-core fuel management, fuel utilization, and storage in the spent fuel pool.

- The back end of the nuclear fuel cycle. The back end of the nuclear fuel cycle involves managing the spent fuel after irradiation. Therefore, the back end of the fuel cycle consists of:

- spent interim fuel storage

- fuel reprocessing,

- final disposal of radioactive waste or spent fuel.

Open Fuel Cycle – Once-through Fuel Cycle

Most countries with nuclear programs use some type of interim storage as their back-end strategy. They have explicitly decided to take a “wait and see” approach to spent fuel management, leaving their spent fuel in interim storage, which leaves both the reprocessing and direct disposal options open for the future. As the name implies, the wait-and-see option proposes interim storage until some solution for permanent storage and disposal is developed in the future. For many operators, the spent fuel represents also a strategic material, since the spent nuclear fuel still contains about 96% of reusable material. Storing spent fuel and waste for several years allows heat release and radioactivity to subside. Despite the continued debate over the future of the fuel cycle, a quiet consensus has developed that simply storing spent fuel while developing more permanent solutions is an attractive approach for the near term. Currently, spent fuel is being stored in at-reactor (AR) or away-from-reactor (APR) storage facilities, and we can identify two basic solutions for interim storage:

- Dry Storage

- Wet Storage

Interim Storage

Interim storage is a temporary solution that plays a central role in managing the most highly radioactive materials: spent nuclear fuel and vitrified waste from reprocessing such fuel. Since spent nuclear fuel is compact, plant operators can store fuel assemblies for a long time. It must be noted that the spent nuclear fuel is due to the presence of a high amount of radioactive fission fragments and transuranic elements that are very hot and very radioactive. Reactor operators must manage the heat and radioactivity that remains in the spent fuel after it’s taken out of the reactor. In nuclear power plants, spent nuclear fuel is usually stored underwater in the spent fuel pool on the plant. Plant personnel moves the spent fuel underwater from the reactor to the pool. Over time, as the spent fuel is stored in the pool, it becomes cooler as the radioactivity decays away. After several years (> 5 years), decay heat decreases under specified limits so that spent fuel may be reprocessed or interim storage.

Dry storage is most often based on the use of spent fuel casks. As its name implies, dry storage of spent fuel assemblies differs from wet storage by using gas or air instead of water as the coolant and metal or concrete instead of water as the radiation barrier. In dry storage systems, sufficiently cooled spent fuel is not stored underwater but loaded in these casks (or vaults or silos). If on-site pool storage capacity is exceeded, it may be desirable to store the spent fuel in modular dry storage facilities, which may be at the reactor site (AR) or a facility away from the site (AFR). Spent fuel is transferred from spent fuel pools to thick metal casks or thinner canisters. These casks are then drained, filled with inert gas, and sealed. The thick casks can be placed directly on a concrete pad, while the thinner canisters are placed in concrete casks or vaults to provide radiation shielding. Many regulators have determined that dry storage of spent fuel at reactor sites is safe for at least 100 years, and generally considers dry storage safer than pool storage.

Types of Nuclear Fuel Cycles

As was written, the back end of the nuclear fuel cycle involves managing the spent fuel after irradiation. Therefore, the back end of the fuel cycle consists of:

- spent interim fuel storage

- fuel reprocessing,

- final disposal of radioactive waste or spent fuel.

There are three main types of nuclear fuel cycle:

- Once-through fuel cycle. An open fuel cycle is not a real cycle, and this strategy assumes that the fuel is used once and sent to long-term storage without further reprocessing. If spent fuel is not reprocessed, the fuel cycle is referred to as an open fuel cycle or a once-through fuel cycle, as the uranium components go through the reactor once. The once-through cycle comprises two main back-end stages:

- interim storage

- final disposal.

- Twice-through fuel cycle. The twice-through cycle strategy assumes that the spent nuclear fuel will be reprocessed to extract the uranium and plutonium, which can be recycled as fresh nuclear fuel for use in a nuclear reactor adapted to this type of fuel.

- Closed fuel cycle. The closed fuel cycle is an advanced fuel cycle whose purpose is to achieve nuclear power sustainability by further reducing the radiotoxicity of the final waste and improving resource utilization while maintaining its economic viability. There are currently different types of advanced fuel cycles under research, but most of them are based on the use of:

- Advanced Nuclear Reactors

- Fuel Reprocessing

These fuel strategies are based on specific processes in the entire fuel cycle (the back end, the front end, and the service period). All these scenarios are theoretical, and the practical solution will combine these options. In all cases, the fuel assemblies are first after irradiation, stored in spent fuel pools at the reactor site for an initial cooling period. It must be added that any strategy for managing spent nuclear fuel will be built around combinations of many options, and all strategies must ultimately include permanent geological disposal.

The choices of nuclear fuel cycle (open, closed, or partially closed through limited spent fuel recycling) depend upon the technologies we develop and societal weighting of goals (safety, economics, waste management, and nonproliferation). Once choices are made, they will have major and long-term impacts on nuclear power development. Today we do not have sufficient knowledge to make informed choices for the best cycles and associated technologies.

See more: The Future of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle. An interdisciplinary MIT study. MIT, 2011. ISBN 978-0-9828008-4-3.