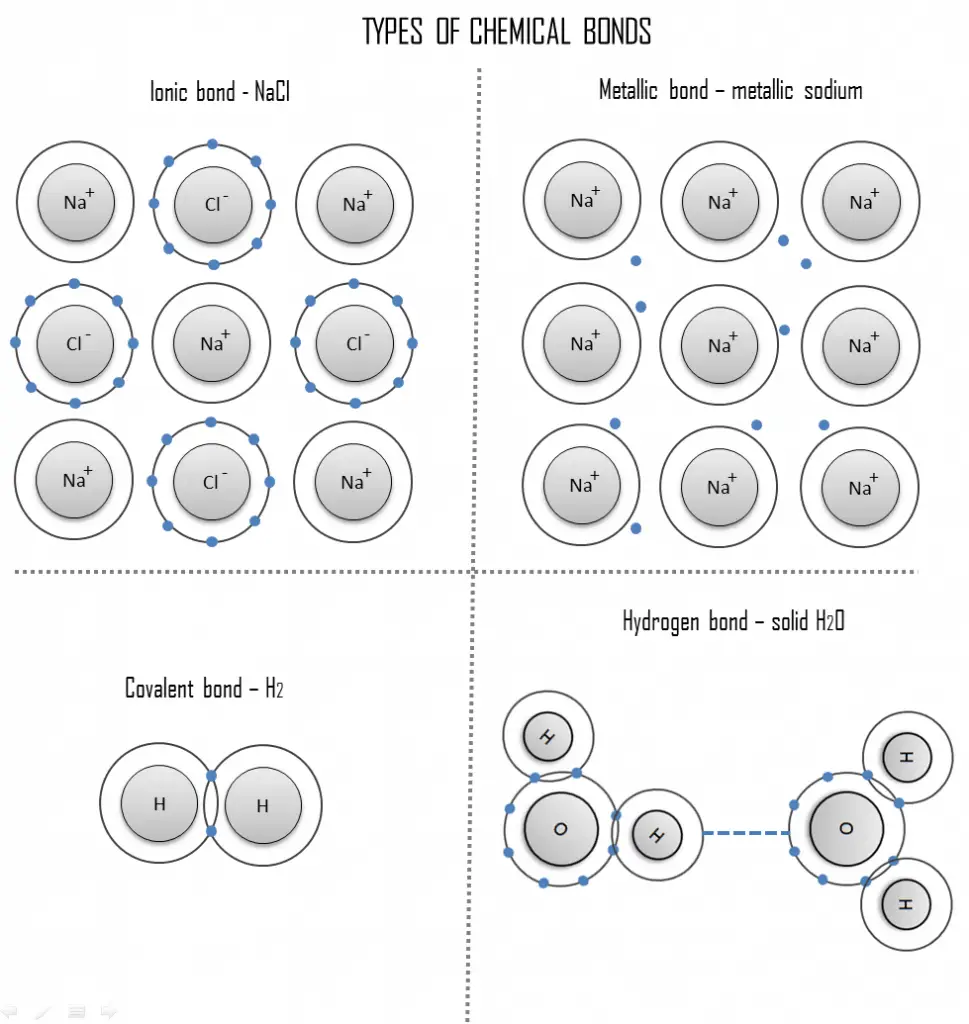

The chemical properties of the atom are determined by the number of protons, in fact, by the number and arrangement of electrons. The configuration of these electrons follows the principles of quantum mechanics and the Pauli exclusion principle. The number of electrons in each element’s electron shells, particularly the outermost valence shell, is the primary factor in determining its chemical bonding behavior. A chemical bond is a lasting attraction between these atoms, ions, or molecules that enables the formation of chemical compounds. The bond may result from the electrostatic force of attraction between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds or through the sharing of electrons as in covalent bonds. Therefore, the electromagnetic force plays a major role in determining the internal properties of most objects encountered in daily life. Three different types of primary or chemical bonds are found in solids:

Intramolecular bonds

- Ionic bond. An ionic bond is a chemical bond in which one or more electrons are wholly transferred from an atom of one element to the atom of the other, and the elements are held together by the force of attraction due to the opposite polarity of the charge. This type of chemical bond is typical between elements with a large electronegativity difference.

- Covalent bond. A covalent bond is a chemical bond formed by shared electrons. Valence electrons are shared when an atom needs electrons to complete its outer shell and can share those electrons with its neighbor. The electrons are then part of both atoms, and both shells are filled.

- Metallic bond. A metallic bond is a chemical bond in which the atoms do not share or exchange electrons to bond together. Instead, many electrons (roughly one for each atom) are more or less free to move throughout the metal so that each electron can interact with many fixed atoms.

Intermolecular bonds

- Molecular bond. When the electrons of neutral atoms spend more time in one region of their orbit, a temporary, weak charge will exist, and the molecule will weakly attract other molecules. This is sometimes called the van der Waals or molecular bonds.

- Hydrogen bond. A hydrogen bond can be intermolecular (occurring between separate molecules) or intramolecular (occurring among parts of the same molecule). The hydrogen bond is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom covalently bound to a more electronegative atom or group.

The strength of chemical bonds varies considerably; there are “primary bonds” or “strong bonds” such as ionic, covalent, and metallic bonds, and “weak bonds” or “secondary bonds” such as dipole-dipole interactions, the London dispersion force, and hydrogen bonding. In this chapter, we will deal primarily with solids because solids are of the most concern in engineering materials applications. Liquids and gases will be mentioned for comparative purposes only. Molecules in solids are bound tightly together. When the attractions are weaker, the substance may be in a liquid form and free to flow. Gases exhibit virtually no attractive forces between atoms or molecules, and their particles are free to move independently of each other.

The type of bond determines how well a material is held together and what microscopic properties the material possesses. Properties such as the ability to conduct heat or electrical current are determined by the free movement of electrons, which depends on the type of bonding present. Knowledge of the material’s microscopic structure allows us to predict how that material will behave under certain conditions.

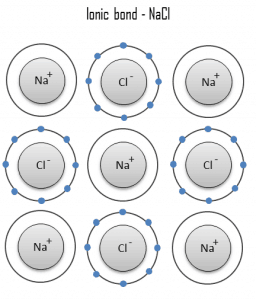

Ionic Bond

An ionic bond is a chemical bond in which one or more electrons are wholly transferred from an atom of one element to the atom of the other, and the elements are held together by the force of attraction due to the opposite polarity of the charge. This type of chemical bond is typical between elements with a large electronegativity difference (i.e., elements situated at the horizontal extremities of the periodic table). An ionic bond is always found in compounds composed of both metallic and nonmetallic elements. There is no precise value that distinguishes ionic from covalent bonding, but an electronegativity difference of over 1.7 is likely to be ionic while a difference of less than 1.7 is likely to be covalent.

An ionic bond is a chemical bond in which one or more electrons are wholly transferred from an atom of one element to the atom of the other, and the elements are held together by the force of attraction due to the opposite polarity of the charge. This type of chemical bond is typical between elements with a large electronegativity difference (i.e., elements situated at the horizontal extremities of the periodic table). An ionic bond is always found in compounds composed of both metallic and nonmetallic elements. There is no precise value that distinguishes ionic from covalent bonding, but an electronegativity difference of over 1.7 is likely to be ionic while a difference of less than 1.7 is likely to be covalent.

Ionic bonding leads to separate positive and negative ions. In the process, all the atoms acquire stable or inert gas configurations (i.e., completely filled orbital shells) and, in addition, an electrical charge – that is, they become ions. For example, common table salt is sodium chloride, and sodium chloride (NaCl) is the classic ionic material. A sodium atom can assume neon’s electron structure by transferring its one valence 3s electron to a chlorine atom. After such a transfer, the chlorine ion acquires a net negative charge, an electron configuration identical to that of argon; it is also larger than the chlorine atom. These ions are then attracted to each other in a 1:1 ratio to form sodium chloride (NaCl).

Na + Cl → Na+ + Cl− → NaCl

Ionic compounds conduct electricity when molten or in solution, typically as a solid. Ionic compounds generally have a high melting point, depending on the charge of the ions they consist of. The higher the charges, the stronger the cohesive forces and the higher the melting point. They also tend to be soluble in water; the stronger the cohesive forces, the lower the solubility.

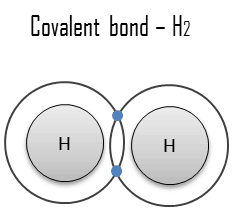

Covalent Bond

A covalent bond is a chemical bond formed by shared electrons. Valence electrons are shared when an atom needs electrons to complete its outer shell and can share those electrons with its neighbor. The electrons are then part of both atoms, and both shells are filled. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs, and the stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms, when they share electrons, is known as covalent bonding.

A covalent bond is a chemical bond formed by shared electrons. Valence electrons are shared when an atom needs electrons to complete its outer shell and can share those electrons with its neighbor. The electrons are then part of both atoms, and both shells are filled. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs, and the stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms, when they share electrons, is known as covalent bonding.

The simplest and most common type is a single bond in which two atoms share two electrons. Other types include the double bond (e.g., H2C=CH2), the triple bond, one- and three-electron bonds, the three-center two-electron bond, and the three-center four-electron bond.

Covalency is greatest between atoms of similar electronegativities. Thus, covalent bonding does not necessarily require that the two atoms be of the same elements, only that they be of comparable electronegativity (i.e., elements that lie near one another in the periodic table). There is no precise value that distinguishes ionic from covalent bonding. Still, an electronegativity difference of over 1.7 is likely to be ionic, while a difference of less than 1.7 is likely to be covalent.

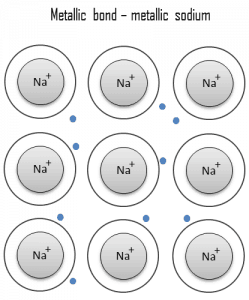

Metallic Bond

A metallic bond is a chemical bond in which the atoms do not share or exchange electrons to bond together. Instead, many electrons (roughly one for each atom) are more or less free to move throughout the metal so that each electron can interact with many fixed atoms. The free electrons shield the positively charged ion cores from the mutually repulsive electrostatic forces they would otherwise exert upon one another; consequently, the metallic bond is nondirectional in character. Metallic bonding is found in metals and their alloys. The free movement or delocalization of bonding electrons leads to classical metallic properties such as luster (surface light reflectivity), electrical and thermal conductivity, ductility, and high tensile strength.

A metallic bond is a chemical bond in which the atoms do not share or exchange electrons to bond together. Instead, many electrons (roughly one for each atom) are more or less free to move throughout the metal so that each electron can interact with many fixed atoms. The free electrons shield the positively charged ion cores from the mutually repulsive electrostatic forces they would otherwise exert upon one another; consequently, the metallic bond is nondirectional in character. Metallic bonding is found in metals and their alloys. The free movement or delocalization of bonding electrons leads to classical metallic properties such as luster (surface light reflectivity), electrical and thermal conductivity, ductility, and high tensile strength.

Metal is a material (usually solid) comprising one or more metallic elements (e.g., iron, aluminum, copper, chromium, titanium, gold, nickel), and often also nonmetallic elements (e.g., carbon, nitrogen, oxygen) in relatively small amounts. The unique feature of metals, as far as their structure is concerned, is the presence of charge carriers, specifically electrons. This feature is given by the nature of the metallic bond. The electrical and thermal conductivities of metals originate from their outer electrons being delocalized.

Hydrogen Bond

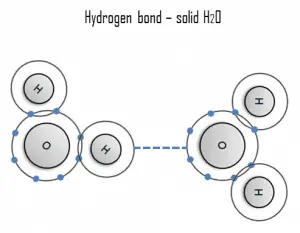

A hydrogen bond can be intermolecular (occurring between separate molecules) or intramolecular (occurring among parts of the same molecule). The hydrogen bond is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom covalently bound to a more electronegative atom or group.

A hydrogen bond can be intermolecular (occurring between separate molecules) or intramolecular (occurring among parts of the same molecule). The hydrogen bond is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom covalently bound to a more electronegative atom or group.

Hydrogen is a strong example of an interaction between two permanent dipoles. The large difference in electronegativities between hydrogen and any fluorine, nitrogen, and oxygen, coupled with their lone pairs of electrons, cause strong electrostatic forces between molecules. A ubiquitous example of a hydrogen bond is found between water molecules. Hydrogen bonds are responsible for the high boiling points of water. Each H2O molecule has two hydrogen atoms that can bond to oxygen atoms, and in addition, its single O atom can bond to two hydrogen atoms of other H2O molecules. Thus, each water molecule participates in four hydrogen bonds for solid ice, helping to create an open hexagonal lattice. Liquid water’s high boiling point is due to the high number of hydrogen bonds each molecule can form, relative to its low molecular mass. Due to the difficulty of breaking these bonds, water has a very high boiling point, melting point, and viscosity compared to similar liquids not conjoined by hydrogen bonds.