In general, the strong interaction is a very complicated interaction because it significantly varies with distance. The strong nuclear force holds most ordinary matter together because it confines quarks into hadron particles such as the proton and neutron. Moreover, the strong force is the force that can hold a nucleus together against the enormous forces of repulsion (electromagnetic force) of the protons is strong indeed.

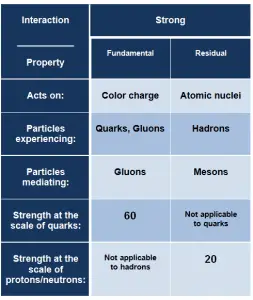

From this point of view, we have to distinguish between:

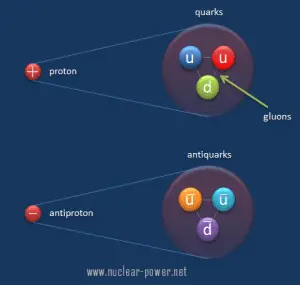

- Fundamental Strong Force. The fundamental strong force, or the strong force, is a very short range (less than about 0.8 fm, the radius of a nucleon) force that acts directly between quarks. This force holds quarks together to form protons, neutrons, and other hadron particles. The strong interaction is mediated by the exchange of massless particles called gluons that act between quarks, antiquarks, and other gluons.

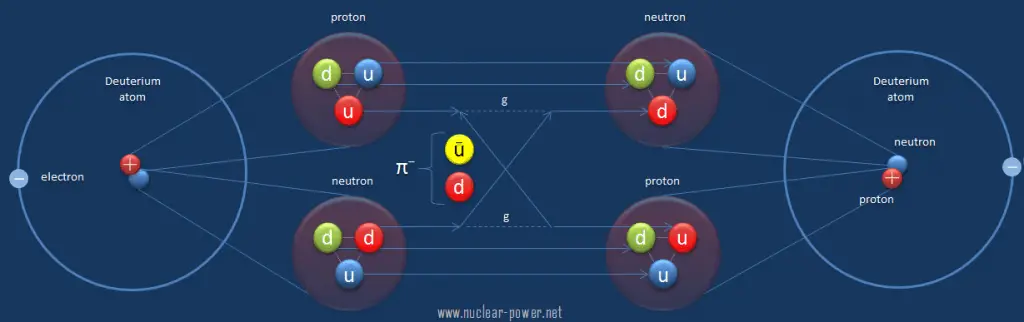

- Residual Strong Force. The residual strong force, also known as the nuclear force, is a very short range (about 1 to 3 fm) force, which acts to hold neutrons and protons together in nuclei. In nuclei, this force acts against the enormous repulsive electromagnetic force of the protons. The term residual is associated with the fact that it is the residuum of the fundamental strong interaction between the quarks that make up the protons and neutrons. The residual strong force acts indirectly through the virtual π and ρ mesons, which transmit the force between nucleons that holds the nucleus together.

In strong interactions, the quarks exchange gluons, the carriers of the strong force. Gluons carry the color charge of a strong nuclear force. Color charge is analogous to electromagnetic charge, but quarks carry three types of color charge (red, green, blue), and antiquarks carry three types of anticolor (antired, antigreen, antiblue). Gluons may be thought of as carrying both color and anticolor.

Most of the mass of a common proton or neutron results from the strong force field energy, and the individual quarks provide only about 1% of the mass of a proton. Noteworthy, because most of your mass is due to the protons and neutrons in your body, your mass (and therefore your weight on a bathroom scale) comes primarily from the gluons that bind the constituent quarks together rather than from the quarks themselves. Mass is primarily a measure of the energies of the quark motion and the quark-binding fields.

Most of the mass of a common proton or neutron results from the strong force field energy, and the individual quarks provide only about 1% of the mass of a proton. Noteworthy, because most of your mass is due to the protons and neutrons in your body, your mass (and therefore your weight on a bathroom scale) comes primarily from the gluons that bind the constituent quarks together rather than from the quarks themselves. Mass is primarily a measure of the energies of the quark motion and the quark-binding fields.

Range of Strong Force

As was written, the strong interaction is a very complicated interaction because it significantly varies with distance. At distances comparable to the diameter of a proton, the strong force is approximately 100 times as strong as the electromagnetic force. However, at smaller distances, the strong force between quarks becomes weaker, and the quarks begin to behave like independent particles. In particle physics, this effect is known as asymptotic freedom.

As a result, the strong force can leak out of individual nucleons (as the residual strong force) to influence the adjacent particle. On the other hand, the strong force cannot reach outside the nucleus. This is due to color confinement, which implies that the strong force acts only between pairs of quarks. Color-charged particles (such as quarks and gluons) cannot be isolated (below Hagedorn temperature). Therefore in collections of bound quarks (i.e., hadrons), the net color-charge of the quarks essentially cancels out, resulting in a limit of the action of the forces.

Strength of Strong Force

It is the strongest of the four fundamental forces, but it significantly varies with distance, as was written. At the scale of quarks, the strong force is approximately 100 times as strong as electromagnetic force, a million times as strong as the weak interaction, and 1043 times as strong as gravitation.

What are Gluons – Mass of Quark

The mass of the neutron is 939.565 MeV/c2, whereas the mass of the three quarks is only about 10 MeV/c2 (only about 1% of the mass-energy of the neutron). Like the proton, most of the mass (energy) of the neutron is in the form of the strong nuclear force energy (gluons). The quarks of the neutron are held together by gluons, the exchange particles for the strong nuclear force. Gluons carry the color charge of a strong nuclear force.

Therefore, we have to distinguish between current quark mass (also called the mass of the ‘naked’ quarks) and constituent quark mass. Current quark mass refers to the mass of a quark by itself, while constituent quark mass refers to the current quark mass plus the mass of the gluon particle field surrounding the quark.

Noteworthy, because most of your mass is due to the protons and neutrons in your body, your mass (and therefore your weight on a bathroom scale) comes primarily from the gluons that bind the constituent quarks together rather than from the quarks themselves. Mass is primarily a measure of the energies of the quark motion and the quark-binding fields of any real object. It must be noted that gluons are inherently massless. They possess energy.

Particles in Strong Interaction

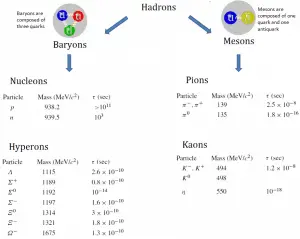

In general, particles that participate in strong interactions are called hadrons: protons and neutrons are hadrons. The hadrons are further sub-divided into baryons and mesons according to the number of quarks they contain. Protons and neutrons each contain three quarks; they belong to the family of particles called the baryons. Other baryons are the lambda, sigma, xi, and omega particles. On the other hand, mesons bosons are composed of two quarks: a quark and an antiquark. Besides charge and spin (1/2 for the baryons), two other quantum numbers are assigned to these particles: baryon number (B) and strangeness (S). Baryons have a baryon number, B, of 1, while their antiparticles, called antibaryons, have a baryon number of −1. A nucleus of deuterium (deuteron), for example, contains one proton and one neutron (each with a baryon number of 1) and has a baryon number of 2. Since baryons make up most of the mass of ordinary atoms, everyday matter is often referred to as baryonic matter.

In general, particles that participate in strong interactions are called hadrons: protons and neutrons are hadrons. The hadrons are further sub-divided into baryons and mesons according to the number of quarks they contain. Protons and neutrons each contain three quarks; they belong to the family of particles called the baryons. Other baryons are the lambda, sigma, xi, and omega particles. On the other hand, mesons bosons are composed of two quarks: a quark and an antiquark. Besides charge and spin (1/2 for the baryons), two other quantum numbers are assigned to these particles: baryon number (B) and strangeness (S). Baryons have a baryon number, B, of 1, while their antiparticles, called antibaryons, have a baryon number of −1. A nucleus of deuterium (deuteron), for example, contains one proton and one neutron (each with a baryon number of 1) and has a baryon number of 2. Since baryons make up most of the mass of ordinary atoms, everyday matter is often referred to as baryonic matter.

The conservation of baryon number is an important rule for interactions and decays of baryons. No known interactions violate the conservation of the baryon number.

Nuclear Force – Residual Strong Force

The residual strong force, also known as the nuclear force, is a very short range (about 1 to 3 fm) force, which acts to hold neutrons and protons together in nuclei. In nuclei, this force acts against the enormous repulsive electromagnetic force of the protons. It acts equally only between pairs of neutrons, pairs of protons, or a neutron and a proton. The term residual is associated with the fact that it is the residuum of the fundamental strong interaction between the quarks that make up the protons and neutrons. The residual strong force acts indirectly through the virtual π and ρ mesons, which transmit the force between nucleons that holds the nucleus together.

As was written, hadrons appear nearly without color charge, and the fundamental strong force is nearly absent between those hadrons, except that the cancellation is not quite perfect. The fundamental strong force can leak out of individual nucleons (as the residual strong force) to influence the adjacent particle. As for the fundamental strong force, the residual force does diminish rapidly with distance and is thus very short-range. Therefore, neither the residual strong force cannot reach outside the nucleus. This is due to color confinement, which implies that the strong force acts only between pairs of quarks. Color-charged particles (such as quarks and gluons) cannot be isolated (below Hagedorn temperature). Therefore in collections of bound quarks (i.e., hadrons), the net color-charge of the quarks essentially cancels out, resulting in a limit of the action of the forces.

Notwithstanding they have an identical origin, the residual strong force is much weaker than the fundamental strong force. It is very much like the electromagnetic forces between neutral atoms (van der Waals forces), which form molecules and are much weaker than the electromagnetic forces that hold electrons associated with the nucleus, forming the atoms.

Atomic nuclei consist of protons and neutrons, which attract each other through the nuclear force, while protons repel each other via electromagnetic force due to their positive charge. These two forces compete, leading to various stability of nuclei. There are only certain combinations of neutrons and protons which form stable nuclei. Neutrons stabilize the nucleus because they attract each other and protons, which helps offset the electrical repulsion between protons. As a result, as the number of protons increases, an increasing ratio of neutrons to protons is needed to form a stable nucleus. Suppose there are too many (neutrons also obey the Pauli exclusion principle) or too few neutrons for a given number of protons. In that case, the resulting nucleus is not stable, and it undergoes radioactive decay. Unstable isotopes decay through various radioactive decay pathways, most commonly alpha decay, beta decay, or electron capture. Many other rare types of decay, such as spontaneous fission or neutron emission, are known.

See also: Liquid Drop Model