Creep, also known as cold flow, is the permanent deformation that increases with time under constant load or stress. It results from long-time exposure to large external mechanical stress within the limit of yielding and is more severe in materials subjected to heat for a long time. The rate of deformation is a function of the material’s properties, exposure time, exposure temperature, and the applied structural load. Creep is very important if we use materials at high temperatures. Creep is very important in the power industry and is of the highest importance in designing jet engines. Time to rupture is the dominant design consideration for many relatively short-life creep situations (e.g., turbine blades in military aircraft). Of course, for its determination, creep tests must be conducted to the point of failure, termed creep rupture tests.

Creep, also known as cold flow, is the permanent deformation that increases with time under constant load or stress. It results from long-time exposure to large external mechanical stress within the limit of yielding and is more severe in materials subjected to heat for a long time. The rate of deformation is a function of the material’s properties, exposure time, exposure temperature, and the applied structural load. Creep is very important if we use materials at high temperatures. Creep is very important in the power industry and is of the highest importance in designing jet engines. Time to rupture is the dominant design consideration for many relatively short-life creep situations (e.g., turbine blades in military aircraft). Of course, for its determination, creep tests must be conducted to the point of failure, termed creep rupture tests.

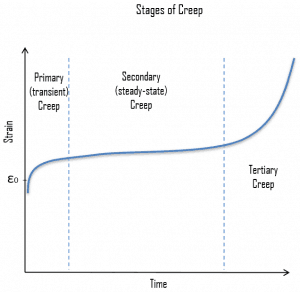

Stages of Creep

As can be seen from the figure, creep is time-dependent, and it goes through several stages:

- Primary Creep. The strain rate is relatively high in the initial stage, or primary creep, or transient creep. Still, it decreases with increasing time and strain because the material is experiencing an increase in creep resistance or strain hardening. This is followed by secondary (or steady-state) creep in Stage II when the creep rate is small, and the strain increases slowly with time.

- Secondary Creep. For secondary creep, sometimes termed steady-state creep, the rate is constant—that is, the plot becomes nearly linear. The strain rate diminishes to a minimum and becomes near constant as the second stage begins. This is due to the balance between work hardening and annealing (thermal softening). This stage of creep is the most understood. The steady-state creep is often the stage of creep that is of the longest duration. No material strength is lost during these first two stages of creep. The most important parameter from a creep test in materials engineering is the slope of the second portion of the creep curve (ΔP/Δt). It is the engineering design parameter that is considered for long-life applications. This parameter is often called the minimum or steady-state creep rate.

- Tertiary Creep. In tertiary creep, there is an acceleration of the rate and possibly ultimate failure. The strain rate exponentially increases with stress because necking phenomena or internal cracks, cavities, or voids decrease the effective area of the specimen. These all lead to a decrease in the effective cross-sectional area and an increase in strain rate. Strength is quickly lost in this stage while the material’s shape is permanently changed. The acceleration of creep deformation in the tertiary stage eventually leads to failure, frequently termed rupture resulting from microstructural and/or metallurgical changes.