The continuity equation is simply a mathematical expression of the principle of conservation of mass. For a control volume with a single inlet and a single outlet, the principle of conservation of mass states that, for steady-state flow, the mass flow rate into the volume must equal the mass flow rate out.

ṁin = ṁout

Mass entering per unit time = Mass leaving per unit time

Conservation of Mass

This principle is generally known as the conservation of matter principle. It states that the mass of an object or collection of objects never changes over time, no matter how the constituent parts rearrange themselves. This principle can be used in the analysis of flowing fluids. Conservation of mass in fluid dynamics states that all mass flow rates into a control volume are equal to all mass flow rates out of the control volume plus the rate of mass change within the control volume.

This principle is expressed mathematically by the following equation:

ṁin = ṁout +∆m⁄∆t

Mass entering per unit time = Mass leaving per unit time + Increase of mass in the control volume per unit time

This equation describes nonsteady-state flow. Nonsteady-state flow refers to the condition where the fluid properties at any single point in the system may change over time. Steady-state flow refers to the condition where the fluid properties (temperature, pressure, and velocity) at any single point in the system do not change over time. But one of the most significant constant properties in a steady-state flow system is the system mass flow rate. This means that there is no accumulation of mass within any component in the system.

Continuity Equation

The continuity equation is simply a mathematical expression of the principle of conservation of mass. For a control volume with a single inlet and a single outlet, the principle of conservation of mass states that, for steady-state flow, the mass flow rate into the volume must equal the mass flow rate out.

ṁin = ṁout

Mass entering per unit time = Mass leaving per unit time

This equation is called the continuity equation for steady one-dimensional flow. The net mass flow must be zero for a steady flow through a control volume with many inlets and outlets, where negative inflows and outflows are positive.

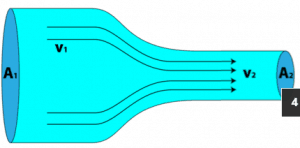

This principle can be applied to a stream tube such as that shown above. No fluid flows across the boundary made by the streamlines, so mass only enters and leaves through the two ends of this stream tube section.

When a fluid is in motion, it must move in such a way that mass is conserved. To see how mass conservation places restrictions on the velocity field, consider the steady flow of fluid through a duct (that is, the inlet and outlet flows do not vary with time).

Differential Form of Continuity Equation

A general continuity equation can also be written in a differential form:

∂⍴⁄∂t + ∇ . (⍴ ͞v) = σ

where

- ∇ . is divergence,

- ρ is the density of quantity q,

- ⍴ ͞v is the flux of quantity q,

- σ is the generation of q per unit volume per unit time. Terms that generate (σ > 0) or remove (σ < 0) q are referred to as a “sources” and “sinks” respectively. If q is a conserved quantity (such as energy), σ is equal to 0.

Continuity Equation – Multiple Inlets and Outlets

For a control volume with multiple inlets and outlets, the principle of conservation of mass requires that the sum of the mass flow rates into the control volume equal the sum of the mass flow rates out of the control volume. The following equation expresses the continuity equation for this more general situation:

∑ṁin = ∑ṁout

Sum of mass flow rates entering per unit time = Sum of mass flow rates leaving per unit time

Continuity Equation – Examples

The flow rate through a reactor core

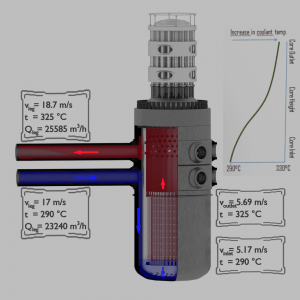

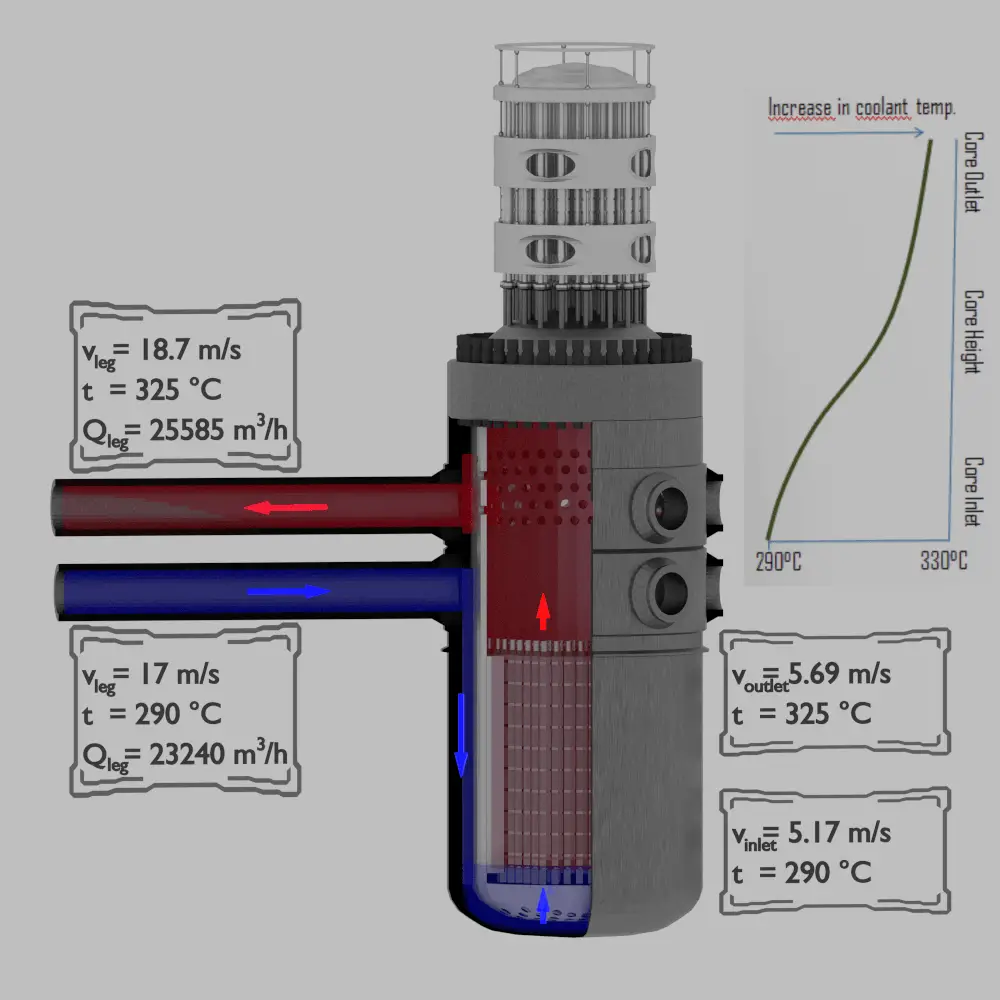

In this example, we will calculate the flow rate through a reactor core from the continuity equation. It is an illustrative example, and the following data do not represent any reactor design.

ṁin = ṁout

(ρAv)in = (ρAv)out

____________________________

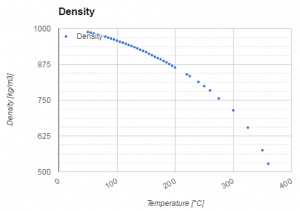

Pressurized water reactors are cooled and moderated by high-pressure liquid water (e.g.,, 16MPa). At this pressure, water boils at approximately 350°C (662°F). The inlet temperature of the water is about 290°C (⍴ ~ 720 kg/m3). The water (coolant) is heated in the reactor core to approximately 325°C (⍴ ~ 654 kg/m3) as the water flows through the core.

The primary circuit of a typical PWR is divided into 4 independent loops (piping diameter ~ 700mm). Each loop comprises a steam generator and one main coolant pump. Inside the reactor pressure vessel (RPV), the coolant first flows down outside the reactor core (through the downcomer). The flow is reversed up through the core from the bottom of the pressure vessel, where the coolant temperature increases as it passes through the fuel rods and the assemblies formed by them.

Calculate:

- the primary piping volumetric flow rate (m3/s),

- the primary piping flow velocity (m/s),

- the core inlet flow velocity (m/s),

- the core outlet flow velocity (m/s)

when

- the mass flow rate in the hot leg of primary piping is equal to 4648 kg/s,

- Reactor core flow cross-section is equal to 5m2,

- Primary piping flow cross-section (single loop) is equal to 0.38 m2

Results:

Cold leg volumetric flow rate:

Qcold = ṁ / ⍴ = 4648 / 720 = 6.46 m3/s = 23240 m3/hod

Cold leg flow velocity:

A1 = π.d2 / 4

vcold = Qcold / A1 = 6.46 / (3.14 x 0.72 / 4) = 6.46 / 0.38 = 17 m/s

Hot leg volumetric flow rate:

Qhot = ṁ / ⍴ = 4648 / 654 = 7.11 m3/s = 25585 m3/hod

Hot leg flow velocity:

A = π.d2 / 4

vhot = Qhot / A1 = 7.11 / (3.14 x 0.72 / 4) = 7.11 / 0.38 = 18,7 m/s

or according to the continuity equation:

⍴1 . A1 . v1 = ⍴2 . A2 . v2

vhot = vcold . ⍴cold / ⍴hot = 17 x 720 / 654 = 18.7 m/s

Core inlet flow velocity:

Acore = 5m2

Apiping = 4 x A1 = 4 x 0.38 = 1.52 m2

⍴inlet = ⍴cold

according to the continuity equation:

⍴inlet . Acore . vinlet = ⍴cold . Apiping . vcold

vinlet = vcold . Apiping / Acore = 17 x 1.52 / 5 = 5.17 m/s

Core outlet flow velocity:

⍴inlet = ⍴cold

⍴outlet = ⍴hot

according to the continuity equation:

⍴outlet . Acore . voutlet = ⍴inlet . Acore . vinlet

voutlet = vinlet . ⍴inlet / ⍴outlet = 5.17 x 720 / 654 = 5.69 m/s