The basic classification of nuclear reactors is based upon the average energy of the neutrons, which cause the bulk of the fissions in the reactor core. From this point of view, nuclear reactors are divided into two categories:

- Thermal Reactors. Almost all of the current reactors built to date use thermal neutrons to sustain the chain reaction. These reactors contain neutron moderator that slows neutrons from fission until their kinetic energy is more or less in thermal equilibrium with the atoms (E < 1 eV) in the system.

- Fast Neutron Reactors. Fast reactors contain no neutron moderator and use less-moderating primary coolants because they use fast neutrons (E > 1 keV) to cause fission in their fuel.

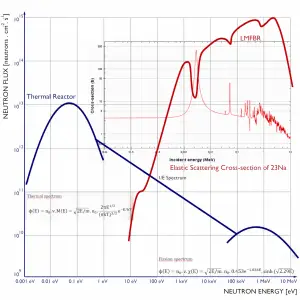

Comparison of neutron spectra in a typical LWR and a sodium-cooled fast breeder reactor. Note that, the fast reactor spectrum is highly affected by the elastic scattering cross-section of used coolant.

Comparison of neutron spectra in a typical LWR and a sodium-cooled fast breeder reactor. Note that, the fast reactor spectrum is highly affected by the elastic scattering cross-section of used coolant.Region of Fast Neutrons

The first part of the neutron flux spectrum in thermal reactors is the region of fast neutrons. All neutrons produced by fission are born as fast neutrons with high kinetic energy.

At first, we have to distinguish between fast neutrons and prompt neutrons. The prompt neutrons can sometimes be incorrectly confused with the fast neutrons. But there is an essential difference between them. Fast neutrons are categorized according to kinetic energy, while prompt neutrons are categorized according to the time of their release.

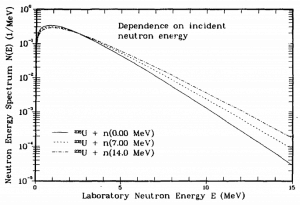

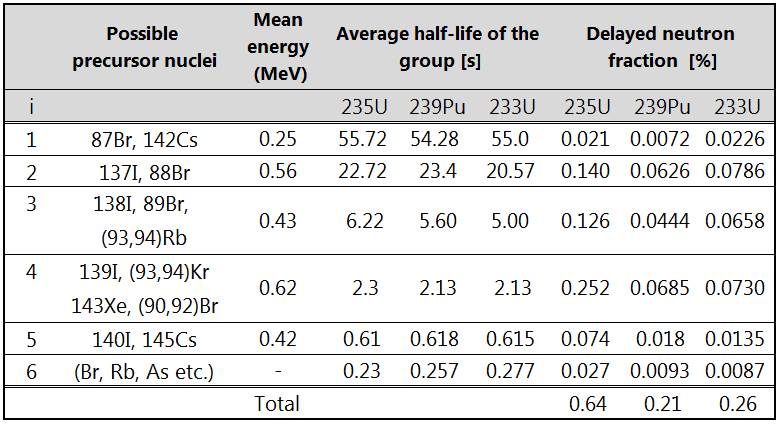

Most of the neutrons produced in fission are prompt neutrons. Usually, more than 99 percent of the fission neutrons are prompt neutrons. Still, the exact fraction is dependent on the nuclide to be fissioned and is also dependent on an incident neutron energy (usually increases with energy). For example, fission of 235U by thermal neutron yields 2.43 neutrons, of which 2.42 neutrons are the prompt neutrons, and 0.01585 neutrons (0.01585/2.43=0.0065=ß) are the delayed neutrons.

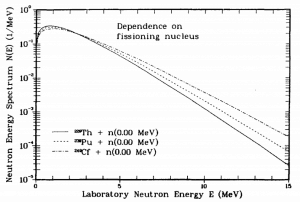

Source: Madland, David G., New Fission-Neutron-Spectrum Representation for ENDF, LA-9285-MS, April 1982.

The vast of the prompt neutrons and even the delayed neutrons are born as fast neutrons (i.e., kinetic energy higher than > 1 keV). But these two groups of fission neutrons have different energy spectra. Therefore they contribute to the fission spectrum differently. Since more than 99 percent of the fission neutrons are the prompt neutrons, it is obvious that they will dominate the entire spectrum.

Therefore the fast neutron spectrum can be described by the following points:

- Almost all fission neutrons have energies between 0.1 MeV and 10 MeV.

- The mean neutron energy is about 2 MeV.

- The most probable neutron energy is about 0.7 MeV.

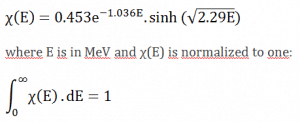

The fast neutron spectrum can be approximated by the following (normalized to one) distribution:

The neutrons released during fission with an average energy of 2 MeV in a reactor on average undergo many collisions (elastic or inelastic) before they are absorbed. As a result of these collisions, they lose energy so that the reactor spectrum is not identical to the fission spectrum. It is always ‘softer’ than the fission spectrum. The fact is that the fission spectrum is part of the reactor spectrum.Thermal vs. Fast Reactors

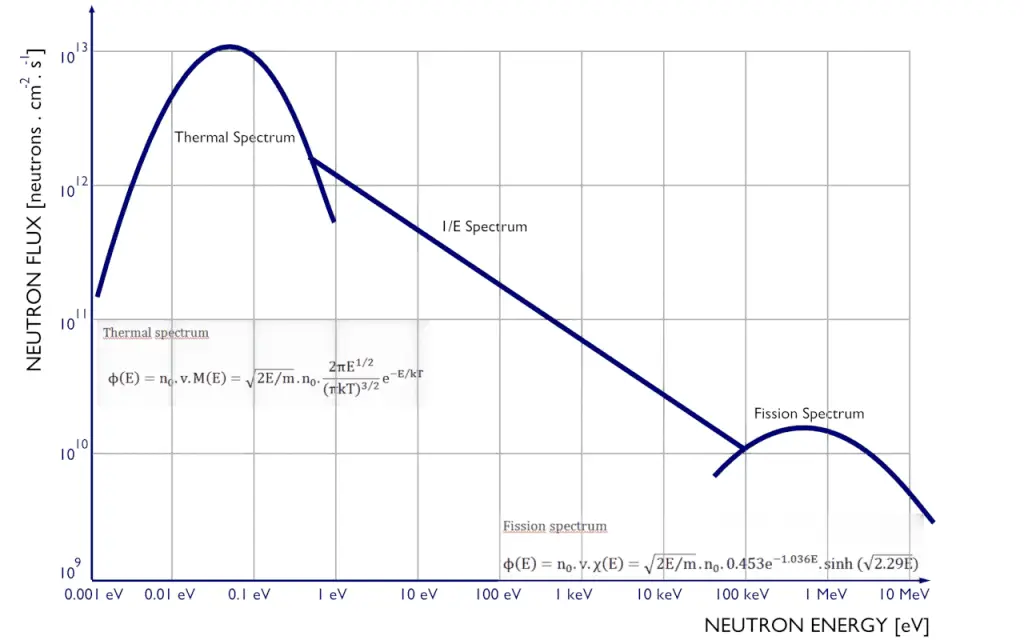

The spectrum of neutron energies produced by fission varies significantly with certain reactor designs. The previous figure illustrates the difference in neutron flux spectra between a thermal reactor and a fast breeder reactor. Note that the neutron spectra in fast reactors also vary significantly with a given reactor coolant. For example, gas-cooled reactors have significantly harder neutron spectra than neutron spectra in sodium-cooled reactors. The main differences in the curve shapes may be attributed to the neutron moderation or slowing down effects.

Intermediate Energy Region

In fast neutron reactors, there is an insignificant number of neutrons that can reach the thermal or intermediate energies. On the other hand, in thermal reactors, neutrons have to be moderated to profit from the larger cross-sections at lower energies. In these reactors, the neutrons are predominantly absorbed only when they are in kinetic equilibrium with the thermal movement of the surrounding atomic nuclei.

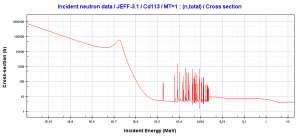

There is an intermediate energy region (1 eV to 0.1 MeV) between the fast and thermal regions. For this region, the 1/E dependency is typical. If the energy (E) is halved, the flux Ф(E) doubles. This 1/E dependence is caused by the nature of the slowing down process. In this region, Σs(E) varies only a little. The elastic scattering removes a constant fraction of the neutron energy per collision (see logarithmic energy decrement), independent of energy. Therefore the neutron loses larger amounts of energy per collision at higher energies than at lower energies. The neutrons lose a constant fraction of kinetic energy per collision causes the energy-dependent neutron flux to “pile up” at lower energies.

Thermal Region

In the thermal region, the neutrons achieve thermal equilibrium with the atoms of the moderator material (in

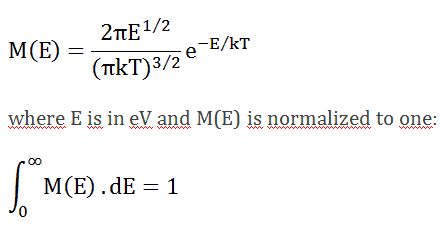

the idealized situation where no absorption is present). That is, the neutrons behave as a strongly diluted gas in thermal equilibrium. These neutrons do not all have the same energy. There is a distribution of energies, usually known as the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution:

in which k is the Boltzmann constant (k = 8.52⋅10-5 eV/K). For the thermal neutron flux density, it thus holds that:

in which k is the Boltzmann constant (k = 8.52⋅10-5 eV/K). For the thermal neutron flux density, it thus holds that:

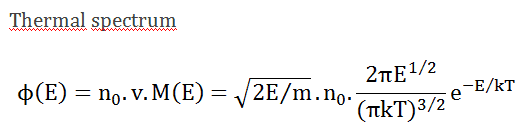

in which n0 is the total thermal neutron density.

in which n0 is the total thermal neutron density.

The most probable energy (for which the spectrum is maximum) is E = kT. At room temperature, this is 0.025 eV. The velocity corresponding with this energy is 2200 m/s. This energy is particularly important since reference data, such as nuclear cross-sections, are tabulated for a neutron velocity of 2200 m/s.

At a reactor temperature of 320°C (593 K), a value characteristic for PWRs, the most probable velocity is 3100 m/s, and the corresponding energy is 0.051 eV.

But this distribution only holds for complete thermal equilibrium. Unfortunately, some absorption will always be present in a nuclear reactor, and this equilibrium will never be complete. As a result of 1/v behavior, low energy neutrons are absorbed preferentially, which leads to a shift of the spectrum to higher energies.

On the other hand, the neutron leakage has an opposite effect. With decreasing energy the diffusion coefficient D decreases as a result of the increasing cross-sections, therefore the neutron leakage preferentially removes neutrons with higher energies. This effect strongly depends on the size of the multiplying system, but in most cases it is much less important than the presence of absorption.

Reactors with Spectral Shift Control

From the physics point of view, the main differences among reactor types arise from differences in their neutron energy spectra. The basic classification of nuclear reactors is based upon the average energy of the neutrons, which cause the bulk of the fissions in the reactor core. The neutron energy spectrum also influences fuel breeding. As was written in LWRs, the fuel temperature also influences the rate of nuclear breeding (the breeding ratio).

Instead of increasing fuel temperature, a reactor can be designed with so-called “spectral shift control”. The main idea of the spectral shift is based on the neutron spectrum shifting from the resonance energy region (with lowest p – resonance escape probability) at the beginning of the cycle to the thermal region (with the highest p – resonance escape probability) at the end of the cycle. In pressurized water reactors, chemical shim (boric acid) and burnable absorbers are used to compensate for an excess of reactivity of reactor core along the fuel burnup (long-term reactivity control). From the neutronic utilization aspect, compensation by absorbing neutrons in poison is not ideal because these neutrons are lost. For better utilization of the neutrons, fertile isotopes can absorb these neutrons to produce fissile nuclei (in radiative capture). These fissile nuclei would contribute to obtaining more energy from the fuel.

The spectral shift method can be used to offset the initial excess of reactivity. There are many different ways of such regulation in the core. Spectral shift control can be performed by coolant density variation during the reactor cycle or by changing the moderator-to-fuel ratio with some mechanical equipment. Some of the current advanced reactor designs use for spectrum shift movable water displacers to change the moderator-to-fuel ratio. A decrease in reactivity caused by fuel burnup is simply compensated by the withdrawal of these movable water displacers while changing the moderator-to-fuel ratio. This makes it possible to exclude chemical shim from the operational modes completely. This method promises significant natural uranium savings (up to 50% of natural uranium).

See also: Teplov, P.; Chibiniaev, A.; Bobrov, E.; Alekseev, P. The main characteristics of the evolution project VVER-S with spectrum shift regulation. 2014.