It can be used to describe internal combustion engines. The pressure-volume diagrams of actual internal combustion engines are not described well by the Otto and Diesel cycles. An air standard cycle that can be made to approximate the pressure variations more closely is the air-standard dual cycle. A more capable approach would be to model the combustion process in both Otto and Diesel engines as a combination of two heat-transfer processes, one isochoric process, and one isobaric process.

Compared to an Otto cycle, which assumes an instantaneous heat addition (isochoric heat addition), heat is added partly at constant volume and partly at constant pressure in a dual cycle. Therefore the advantage is that more time is available for the fuel to combust completely. On the other hand, the use of a dual cycle is slightly more complex. The thermal efficiency lies between Otto and Diesel cycle.

Dual Cycle – Processes

In a dual cycle, the system executing the cycle undergoes a series of five processes: two isentropic (reversible adiabatic) processes alternated with two isochoric processes and one isobaric process:

-

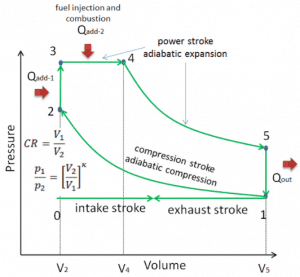

Dual cycle – pV Diagram Isentropic compression (compression stroke) – The gas is compressed adiabatically from state 1 to state 2, as the piston moves from intake valve closing point (1) to top dead center. The surroundings do work on the gas, increasing its internal energy (temperature) and compressing it. On the other hand, the entropy remains unchanged. The changes in volumes and their ratio (V1 / V2) are known as the compression ratio. The compression ratio is smaller than the expansion ratio.

- Isochoric compression (ignition phase) – In this phase (between state 2 and state 3), there is a constant volume (the piston is at rest ) heat transfer to the air from an external source while the piston is at rest at the top dead center. This process is similar to the isochoric process in the Otto cycle. It is intended to represent the ignition of the fuel-air mixture injected into the chamber and the subsequent rapid burning. The pressure rises, and the ratio (P3 / P2) is known as the “explosion ratio”.

- Isobaric expansion (power stroke) – In this phase (between state 3 and state 4), there is a constant pressure (idealized model) heat transfer to the air from an external source (combustion of the fuel) while the piston is moving toward the V4. During the constant pressure process, energy enters the system as heat Qadd, and a part of the work is done by moving pistons.

- Isentropic expansion (power stroke) – The gas expands adiabatically from state 4 to state 5 as the piston moves from V3 to the bottom dead center. The gas works on the surroundings (piston) and loses an amount of internal energy equal to the work that leaves the system. Again the entropy remains unchanged.

- Isochoric decompression (exhaust stroke) – In this phase, the cycle completes by a constant-volume process in which heat is rejected from the air while the piston is at the bottom dead center. The working gas pressure drops instantaneously from point 5 to point 1. The exhaust valve opens at point 5. The exhaust stroke is directly after this decompression. As the piston moves from the bottom dead center (point 1) to the top dead center (point 0) with the exhaust valve opened, the gaseous mixture is vented to the atmosphere, and the process starts anew.

During the Dual cycle, the piston works on the gas between states 1 and 2 (isentropic compression). The gas works on the piston between stages 2 and 3 (isobaric heat addition) and stages 2 and 3 (isentropic expansion). The difference between the work done by the gas and the work done on the gas is the network produced by the cycle, and it corresponds to the area enclosed by the cycle curve. The work produced by the cycle times the rate of the cycle (cycles per second) is equal to the power produced by the Diesel engine.

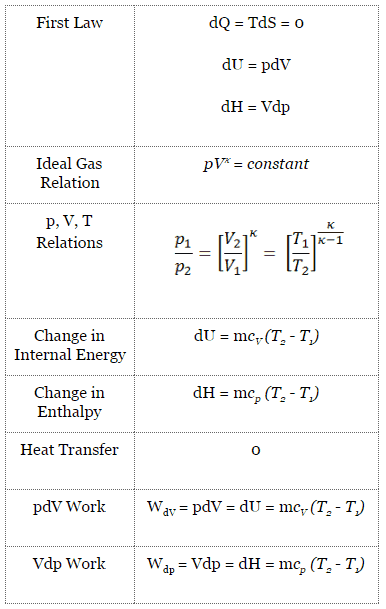

Isentropic Process

An isentropic process is a thermodynamic process in which the entropy of the fluid or gas remains constant. It means the isentropic process is a special case of an adiabatic process in which there is no transfer of heat or matter. It is a reversible adiabatic process. The assumption of no heat transfer is very important since we can use the adiabatic approximation only in very rapid processes.

Isentropic Process and the First Law

For a closed system, we can write the first law of thermodynamics in terms of enthalpy:

dH = dQ + Vdp

or

dH = TdS + Vdp

Isentropic process (dQ = 0):

dH = Vdp → W = H2 – H1 → H2 – H1 = Cp (T2 – T1) (for ideal gas)

Isentropic Process of the Ideal Gas

The isentropic process (a special case of the adiabatic process) can be expressed with the ideal gas law as:

pVκ = constant

or

p1V1κ = p2V2κ

in which κ = cp/cv is the ratio of the specific heats (or heat capacities) for the gas. One for constant pressure (cp) and one for constant volume (cv). Note that, this ratio κ = cp/cv is a factor in determining the speed of sound in a gas and other adiabatic processes.

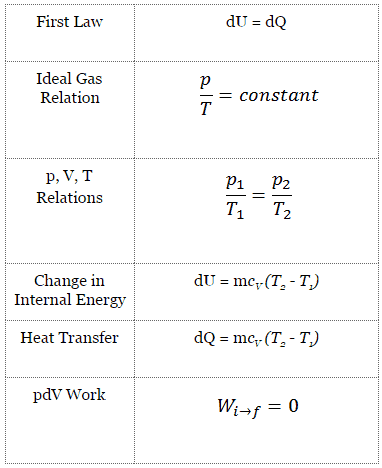

Isochoric Process

An isochoric process is a thermodynamic process in which the volume of the closed system remains constant (V = const). It describes the behavior of gas inside the container that cannot be deformed. Since the volume remains constant, the heat transfer into or out of the system does not the p∆V work but only changes the system’s internal energy (the temperature).

Isochoric Process and the First Law

The classical form of the first law of thermodynamics is the following equation:

dU = dQ – dW

In this equation, dW is equal to dW = pdV and is known as the boundary work. Then:

dU = dQ – pdV

An isochoric process and the ideal gas, all of the heat added to the system, will increase the internal energy.

Isochoric process (pdV = 0):

dU = dQ (for ideal gas)

dU = 0 = Q – W → W = Q (for ideal gas)

Isochoric Process of the Ideal Gas

The isochoric process can be expressed with the ideal gas law as:

or

On a p-V diagram, the process occurs along a horizontal line with the equation V = constant.

See also: Guy-Lussac’s Law.

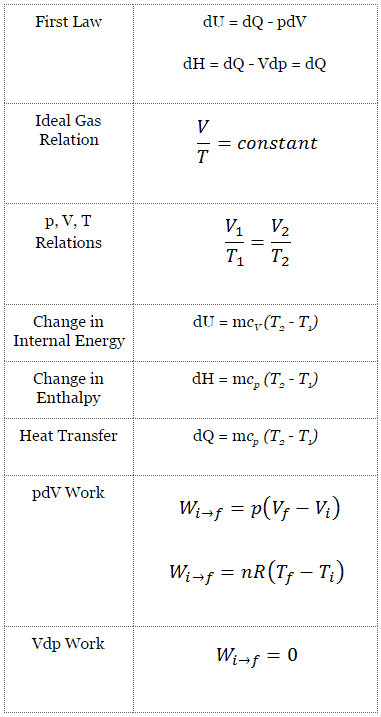

Isobaric Process

An isobaric process is a thermodynamic process in which the system’s pressure remains constant (p = const). The heat transfer into or out of the system does work and changes the system’s internal energy.

Since there are changes in internal energy (dU) and changes in system volume (∆V), engineers often use the enthalpy of the system, which is defined as:

H = U + pV

Isobaric Process and the First Law

The classical form of the first law of thermodynamics is the following equation:

dU = dQ – dW

In this equation dW is equal to dW = pdV and is known as the boundary work. In an isobaric process and the ideal gas, part of the heat added to the system will be used to do work, and part of the heat added will increase the internal energy (increase the temperature). Therefore it is convenient to use enthalpy instead of internal energy.

Isobaric process (Vdp = 0):

dH = dQ → Q = H2– H1

At constant entropy, i.e., in the isentropic process, the enthalpy change equals the flow process work done on or by the system.

Isobaric Process of the Ideal Gas

The isobaric process can be expressed with the ideal gas law as:

or

On a p-V diagram, the process occurs along a horizontal line (called an isobar) with the equation p = constant.

See also: Charles’s Law

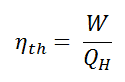

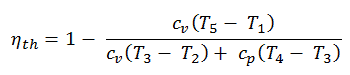

Thermal Efficiency for Dual Cycle

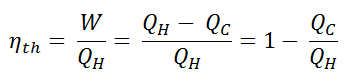

In general, the thermal efficiency, ηth, of any heat engine is defined as the ratio of the work it does, W, to the heat input at the high temperature, QH.

The thermal efficiency, ηth, represents the fraction of heat, QH, converted to work. Since energy is conserved according to the first law of thermodynamics and energy cannot be converted to work completely, the heat input, QH, must equal the work done, W, plus the heat that must be dissipated as waste heat QC into the environment. Therefore we can rewrite the formula for thermal efficiency as:

Therefore the heat added and rejected are given by:

Qadd-1 = mcv (T3 – T2)

Qadd-2 = mcp (T4 – T3)

Qout = mcv (T5 – T1)

Therefore the thermal efficiency for a dual cycle is: