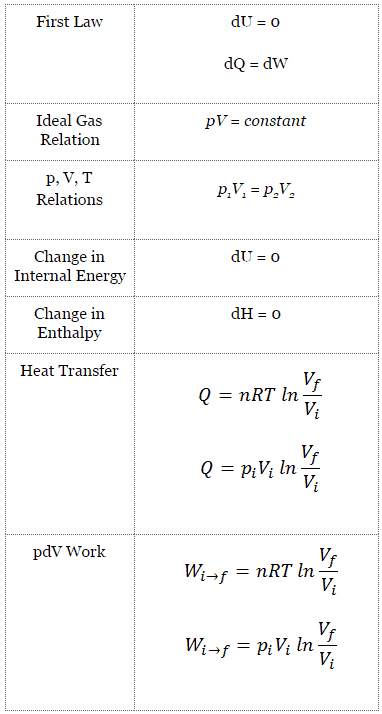

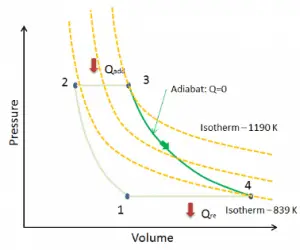

The case n = 1 corresponds to an isothermal (constant-temperature) process for an ideal gas and a polytropic process. In contrast to the adiabatic process, in which n = κ and a system exchanges no heat with its surroundings (Q = 0; ∆T≠0), in an isothermal process, there is no change in the internal energy (due to ∆T=0) and therefore ΔU = 0 (for ideal gases) and Q ≠ 0. An adiabatic process is not necessarily an isothermal process, nor is an isothermal process necessarily adiabatic.

In engineering, phase changes, such as evaporation or melting, are isothermal processes when, as is usually the case, they occur at constant pressure and temperature.

Isothermal Process and the First Law

The classical form of the first law of thermodynamics is the following equation:

dU = dQ – dW

In this equation, dW is equal to dW = pdV and is known as the boundary work.

In the isothermal process and the ideal gas, all heat added to the system will be used to do work:

Isothermal process (dU = 0):

dU = 0 = Q – W → W = Q (for ideal gas)

Isothermal Expansion – Isothermal Compression

See also: What is an Ideal Gas.

In an ideal gas, molecules have no volume and do not interact. According to the ideal gas law, pressure varies linearly with temperature and quantity and inversely with volume.

In an ideal gas, molecules have no volume and do not interact. According to the ideal gas law, pressure varies linearly with temperature and quantity and inversely with volume.

pV = nRT

where:

- p is the absolute pressure of the gas

- n is the amount of substance

- T is the absolute temperature

- V is the volume

- R is the ideal, or universal, gas constant, equal to the product of the Boltzmann constant and the Avogadro constant,

In this equation, the symbol R is a constant called the universal gas constant that has the same value for all gases—namely, R = 8.31 J/mol K.

The isothermal process can be expressed with the ideal gas law as:

pV = constant

or

p1V1 = p2V2

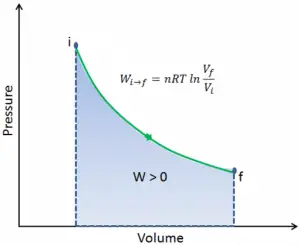

On a p-V diagram, the process occurs along a line (called an isotherm) that has the equation p = constant / V.

Boyle–Mariotte Law

Boyle-Mariotte Law is one of the gas laws. At the end of the 17th century, Robert William Boyle and Edme Mariotte independently studied the relationship between the volume and pressure of a gas at a constant temperature. Certain experiments with gases at relatively low pressure led Robert Boyle to formulate a well-known law. It states that:

For a fixed mass of gas at a constant temperature, the volume is inversely proportional to the pressure.

That means that, for example, if you increase the volume 10 times, the pressure will decrease 10 times. If you halve the volume, you will double the pressure.

You can express this mathematically as:

pV = constant

or

p1V1 = p2V2

Yes, it seems to be identical to the isothermal process of an ideal gas. In fact, during their experiments, the temperature remained constant, as was assumed by Mariotte. These results are fully consistent with the ideal gas law, which determinates that the constant is equal to nRT.

pV = nRT

where:

- p is the absolute pressure of the gas

- n is the amount of substance

- T is the absolute temperature

- V is the volume

- R is the ideal, or universal, gas constant, equal to the product of the Boltzmann constant and the Avogadro constant,

In this equation, the symbol R is a constant called the universal gas constant that has the same value for all gases—namely, R = 8.31 J/mol K.

Example of Isothermal Process

Assume an isothermal expansion of helium (i → f) in a frictionless piston (closed system). The absorption of heat energy Qadd propels the gas expansion. The gas expands from an initial volume of 0.001 m3, and simultaneously the external load of the piston slowly and continuously decreases from 1 MPa to 0.5 MPa. Since helium behaves almost as an ideal gas, use the ideal gas law to calculate the final volume of the chamber and then calculate the work done by the system when the temperature of the gas is equal to 400 K.

Solution:

The final volume of the gas, Vf, can be calculated using p, V, T Relation for isothermal process:

piVi = pfVf ⇒ Vf = piVi / pf = 2 x 0.001 m3 = 0.002 m3

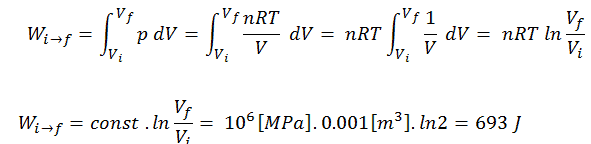

To calculate such processes, we would need to know how pressure varies with volume for the actual process by which the system changes from state i to state f. Since during this process the internal pressure was not constant, the p∆V work done by the piston must be calculated using the following integral:

By convention, a positive value for work indicates that the system in its surroundings does work. A negative value indicates that work is done on the system by its surroundings. The pΔV work is equal to the area under the process curve plotted on the pressure-volume diagram.

Free Expansion – Joule Expansion

These are adiabatic processes in which no heat transfer occurs between the system and its environment, and no work is done on or by the system. These types of adiabatic processes are called free expansion. It is an irreversible process in which a gas expands into an insulated evacuated chamber. It is also called Joule expansion. For an ideal gas, the temperature doesn’t change (the process is also isothermal). However, real gases experience a temperature change during free expansion. In free expansion, Q = W = 0, and the first law requires that:

dEint = 0

A free expansion can not be plotted on a P-V diagram because the process is rapid, not quasistatic. The intermediate states are not equilibrium states, and hence the pressure is not clearly defined.