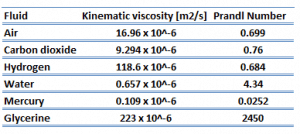

Small values of the Prandtl number, Pr << 1, mean the thermal diffusivity dominates. Whereas with large values, Pr >> 1, the momentum diffusivity dominates the behavior. For example, the typical value for liquid mercury, about 0.025, indicates that heat conduction is more significant than convection, so thermal diffusivity is dominant.

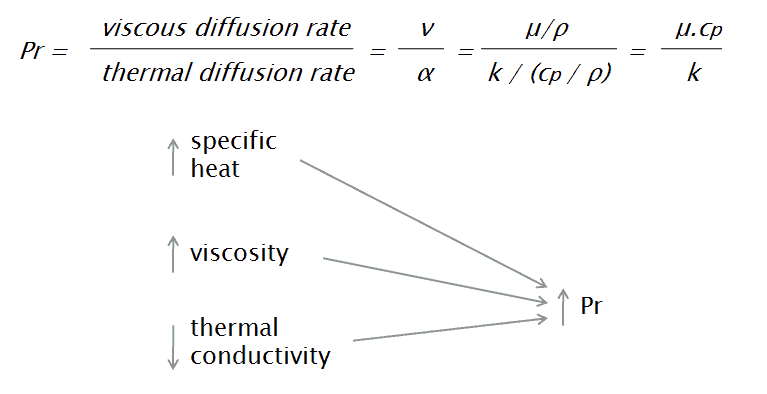

The Prandtl number is a dimensionless number, named after its inventor, a German engineer Ludwig Prandtl, who also identified the boundary layer. The Prandtl number is defined as the ratio of momentum diffusivity to thermal diffusivity. The momentum diffusivity, or as it is normally called, kinematic viscosity, tells us the material’s resistance to shear-flows (different layers of the flow travel with different velocities due to, e.g., different speeds of adjacent walls) in relation to density. That is, the Prandtl number is given as:

where:

ν is momentum diffusivity (kinematic viscosity) [m2/s]

α is thermal diffusivity [m2/s]

μ is dynamic viscosity [N.s/m2]

k is thermal conductivity [W/m.K]

cp is specific heat [J/kg.K]

ρ is density [kg/m3]

Small values of the Prandtl number, Pr << 1, mean the thermal diffusivity dominates. Whereas with large values, Pr >> 1, the momentum diffusivity dominates the behavior. For example, the typical value for liquid mercury, about 0.025, indicates that heat conduction is more significant than convection, so thermal diffusivity is dominant. When Pr is small, it means that the heat diffuses quickly compared to the velocity.

Small values of the Prandtl number, Pr << 1, mean the thermal diffusivity dominates. Whereas with large values, Pr >> 1, the momentum diffusivity dominates the behavior. For example, the typical value for liquid mercury, about 0.025, indicates that heat conduction is more significant than convection, so thermal diffusivity is dominant. When Pr is small, it means that the heat diffuses quickly compared to the velocity.

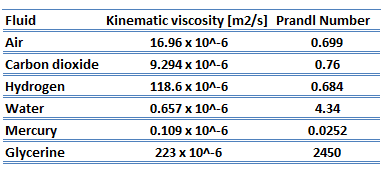

In comparison to the Reynolds number, the Prandtl number is not dependent on the geometry of an object involved in the problem but is dependent solely on the fluid and the fluid state. The Prandtl number is often found in property tables alongside other properties such as viscosity and thermal conductivity.

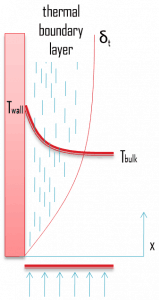

Thermal Boundary Layer

Similarly, as a velocity boundary layer develops when there is fluid flow over a surface, a thermal boundary layer must develop if the bulk temperature and surface temperature differ. Consider flow over an isothermal flat plate at a constant temperature of Twall. At the leading edge, the temperature profile is uniform with Tbulk. Fluid particles that come into contact with the plate achieve thermal equilibrium at the plate’s surface temperature. At this point, energy flow occurs at the surface purely by conduction. These particles exchange energy with those in the adjoining fluid layer (by conduction and diffusion), and temperature gradients develop in the fluid. The region of the fluid in which these temperature gradients exist is the thermal boundary layer. Its thickness, δt, is typically defined as the distance from the body at which the temperature is 99% of the temperature found from an inviscid solution. With increasing distance from the leading edge, heat transfer effects penetrate farther into the stream, and the thermal boundary layer grows.

Similarly, as a velocity boundary layer develops when there is fluid flow over a surface, a thermal boundary layer must develop if the bulk temperature and surface temperature differ. Consider flow over an isothermal flat plate at a constant temperature of Twall. At the leading edge, the temperature profile is uniform with Tbulk. Fluid particles that come into contact with the plate achieve thermal equilibrium at the plate’s surface temperature. At this point, energy flow occurs at the surface purely by conduction. These particles exchange energy with those in the adjoining fluid layer (by conduction and diffusion), and temperature gradients develop in the fluid. The region of the fluid in which these temperature gradients exist is the thermal boundary layer. Its thickness, δt, is typically defined as the distance from the body at which the temperature is 99% of the temperature found from an inviscid solution. With increasing distance from the leading edge, heat transfer effects penetrate farther into the stream, and the thermal boundary layer grows.

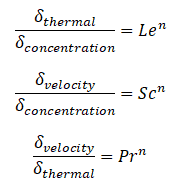

The ratio of these two thicknesses (velocity and thermal boundary layers) is governed by the Prandtl number, defined as the ratio of momentum diffusivity to thermal diffusivity. A Prandtl number of unity indicates that momentum and thermal diffusivity are comparable, and velocity and thermal boundary layers almost coincide with each other. If the Prandtl number is less than 1, which is the case for air at standard conditions, the thermal boundary layer is thicker than the velocity boundary layer. If the Prandtl number is greater than 1, the thermal boundary layer is thinner than the velocity boundary layer. Air at room temperature has a Prandtl number of 0.71, and for water, at 18°C, it is around 7.56, which means that the thermal diffusivity is more dominant for air than for water.

The ratio of these two thicknesses (velocity and thermal boundary layers) is governed by the Prandtl number, defined as the ratio of momentum diffusivity to thermal diffusivity. A Prandtl number of unity indicates that momentum and thermal diffusivity are comparable, and velocity and thermal boundary layers almost coincide with each other. If the Prandtl number is less than 1, which is the case for air at standard conditions, the thermal boundary layer is thicker than the velocity boundary layer. If the Prandtl number is greater than 1, the thermal boundary layer is thinner than the velocity boundary layer. Air at room temperature has a Prandtl number of 0.71, and for water, at 18°C, it is around 7.56, which means that the thermal diffusivity is more dominant for air than for water.

Similarly, as for Prandtl Number, the Lewis number physically relates the relative thickness of the thermal layer and mass-transfer (concentration) boundary layer. The Schmidt number physically relates the relative thickness of the velocity boundary layer and mass-transfer (concentration) boundary layer.

where n = 1/3 for most applications in all three relations. These relations, in general, are applicable only for laminar flow and are not applicable to turbulent boundary layers since turbulent mixing, in this case, may dominate the diffusion processes.

Prandtl Number of Water and Air

Air at room temperature has a Prandtl number of 0.71, and for water, at 18°C, it is around 7.56, which means that the thermal diffusivity is more dominant for air than for water. For a Prandtl number of unity, the momentum diffusivity equals the thermal diffusivity, and the mechanism and rate of heat transfer are similar to those for momentum transfer. For many fluids, Pr lies in the range from 1 to 10, and for gases, Pr is generally about 0.7.

Prandtl Number of Liquid Metals

For liquid metals, the Prandtl number is very small, generally in the range from 0.01 to 0.001. This means that the thermal diffusivity, which is related to the rate of heat transfer by conduction, unambiguously dominates. This very high thermal diffusivity results from metals’ very high thermal conductivity, which is about 100 times higher than water. The Prandtl number for sodium at a typical operating temperature in the Sodium-cooled fast reactors is about 0.004.

The Prandtl number enters many calculations of heat transfer in liquid metal reactors. Two promising designs of Generation IV reactors use liquid metal as the reactor coolant. The development of Generation IV reactors represents a challenge from an engineering point of view.

- Sodium-cooled fast reactor

- Lead-cooled fast reactor

One of the main challenges in numerical simulation is the reliable modeling of heat transfer in liquid metal-cooled reactors by Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). Heat transfer applications with low-Prandtl number fluids are often in the transition range between conduction and convection-dominated regimes.

Laminar Prandtl Number – Turbulent Prandtl Number

When dealing with Prandtl numbers, we have to define a laminar part of the Prandtl number and a turbulent part of the Prandtl number. The equation Pr = ν/α shows us only the laminar part that is only valid for laminar flows. The following equation shows us the effective Prandtl number:

Preff = ν/α + νt/αt

where νt is kinematic turbulent viscosity, and αt is turbulent thermal diffusivity. The turbulent Prandtl number (Prt = νt/αt) is a non-dimensional term defined as the ratio between the momentum eddy diffusivity and the heat transfer eddy diffusivity. It simply describes mixing because of the swirling/rotation of fluids. The simplest model for Prt is the Reynolds analogy, which yields a turbulent Prandtl number of 1.

The velocity and temperature profiles are identical in the special case where the Prandtl number and turbulent Prandtl number both equal unity (as in the Reynolds analogy). This greatly simplifies the solution of the heat transfer problem. The turbulent Prandtl number is around 0.7 for different free shear layers from experimental data. For near-wall flows, it is larger (Prt = 0.9) and occasionally beyond 1 since it tends to grow larger when nearing the walls.