High-purity germanium detectors (HPGe detectors) are the best solution for precise gamma and x-ray spectroscopy. Compared to silicon detectors, germanium is much more efficient than silicon for radiation detection due to its atomic number being much higher than silicon and lower average energy necessary to create an electron-hole pair, which is 3.6 eV for silicon and 2.9 eV for germanium. Due to its higher atomic number, Ge has a much larger linear attenuation coefficient, which leads to a shorter mean free path. Moreover, silicon detectors cannot be thicker than a few millimeters. At the same time, germanium can have a depleted, sensitive thickness of centimeters. It, therefore, can be used as a total absorption detector for gamma rays up to a few MeV.

Before current purification techniques were refined, germanium crystals could not be produced with purity sufficient to enable their use as spectroscopy detectors. The purity of a detector material is of the highest importance. The electron-hole pair collection within the detector must be done reasonably quickly. Moreover, there must be no traps preventing them from reaching the collecting contacts. Trapping centers can be due to:

- Impurities within the semiconductor lattice

- Interstitial atoms and vacancies within the lattice due to structural defects

- Interstitial atoms caused by radiation damage

Impurities in the crystals trap electrons and holes, ruining the performance of the detectors. Consequently, germanium crystals were doped with lithium ions (Ge(Li)) to produce an intrinsic region in which the electrons and holes could reach the contacts and produce a signal.

To achieve maximum efficiency, the HPGe detectors must operate at very low temperatures of liquid nitrogen (-196°C) because the noise caused by thermal excitation is very high at room temperatures.

Since HPGe detectors produce the highest resolution commonly available today, they are used to measure radiation in a variety of applications, including personnel and environmental monitoring for radioactive contamination, medical applications, radiometric assay, nuclear security, and nuclear plant safety.

Parts of HPGe Detectors

The major drawback of germanium detectors is that they must be cooled to liquid nitrogen temperatures. Because germanium has a relatively low band gap, these detectors must be cooled to reduce the thermal generation of charge carriers to an acceptable level. Otherwise, leakage current-induced noise destroys the energy resolution of the detector. Recall that the band gap (a distance between valence and conduction band) is very low for germanium (Egap= 0.67 eV). Cooling to liquid nitrogen temperature (-195.8°C; -320°F) reduces thermal excitations of valence electrons so that only a gamma-ray interaction can give an electron the energy necessary to cross the band gap and reach the conduction band.

Therefore, HPGe detectors are usually equipped with a cryostat. Germanium crystals are maintained within an evacuated metal container called the detector holder. The detector holder and the “end-cap” are thin to avoid attenuation of low-energy photons. The holder is generally made of aluminum and is typically 1 mm thick. The end-cap is also generally made of aluminum. The HPGe crystal inside the holder is in thermal contact with a metal rod called a cold finger. The cold finger transfers heat from the detector assembly to the liquid nitrogen (LN2) reservoir. The combination of the vacuum metal container, the cold finger, and the Dewar flask for the liquid nitrogen cryogen is called the cryostat. The germanium detector preamplifier is normally included as part of the cryostat package. Since the preamp should be located as close as possible so that the overall capacitance can be minimized, the preamp is installed together. The input stages of the preamp are also cooled. The cold finger extends past the vacuum boundary of the cryostat into a Dewar flask filled with liquid nitrogen. The immersion of the cold finger into the liquid nitrogen maintains the HPGe crystal at a constant low temperature. The temperature of the liquid nitrogen is held constant at 77 K (-195.8°C; -320°F) by slow boiling of the liquid, resulting in the evolution of nitrogen gas. Depending on the size and design, the holding time of vacuum flasks ranges from a few hours to a few weeks.

Cooling with liquid nitrogen is inconvenient, as the detector requires hours to cool down to operating temperature before it can be used and cannot be allowed to warm up during use. HPGe detectors can be allowed to warm up to room temperature when not in use. It must be noted that Ge(Li) crystals could never be allowed to warm up, as the lithium would drift out of the crystal, ruining the detector.

Commercial systems became available that use advanced refrigeration techniques (for example, a pulse tube cooler) to eliminate the need for liquid nitrogen cooling. This cooling system is an electrically powered cryostat, completely LN2-free.

See also: Germanium Detectors, MIRION Technologies. <available from: https://www.mirion.com/products/germanium-detectors>.

HPGe Detector – Principle of Operation

The operation of semiconductor detectors is summarized in the following points:

- Ionizing radiation enters the sensitive volume (germanium crystal) of the detector and interacts with the semiconductor material.

- A high-energy photon passing through the detector ionizes the atoms of the semiconductor, producing electron-hole pairs. The number of electron-hole pairs is proportional to the energy of the radiation to the semiconductor. As a result, many electrons are transferred from the valence band to the conduction band, and an equal number of holes are created in the valence band.

- Since germanium can have a depleted, sensitive thickness of centimeters, it can absorb high-energy photons totally (up to a few MeV).

- Under the influence of an electric field, electrons and holes travel to the electrodes, resulting in a pulse that can be measured in an outer circuit.

- This pulse carries information about the energy of the original incident radiation. The number of such pulses per unit time also gives information about the intensity of the radiation.

In all cases, a photon deposits a portion of its energy along its path and can be absorbed totally. Total absorption of a 1 MeV photon produces around 3 x 105 electron-hole pairs. This value is minor compared to the total number of free carriers in a 1 cm3 intrinsic semiconductor. Particle passing through the detector ionizes the atoms of the semiconductor, producing the electron-hole pairs. But in germanium-based detectors at room temperature, thermal excitation is dominant. It is caused by impurities, irregularity in structure lattice, or by dopant. It strongly depends on the Egap (a distance between valence and conduction band), which is very low for germanium (Egap= 0.67 eV). Since thermal excitation results in the detector noise, active cooling is required for some types of semiconductors (e.g., germanium).

![]() Note that a 1 cm3 sample of pure germanium at 20 °C contains about 4.2×1022 atoms but also contains about 2.5 x 1013 free electrons and 2.5 x 1013 holes constantly generated from thermal energy. As can be seen, the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) would be minimal (compare it with 3 x 105 electron-hole pairs). Adding 0.001% of arsenic (an impurity) donates an extra 1017 free electrons in the same volume, and the electrical conductivity is increased by a factor of 10,000. The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) in doped material would be even smaller. Because germanium has a relatively low band gap, these detectors must be cooled to reduce the thermal generation of charge carriers (thus reverse leakage current) to an acceptable level. Otherwise, leakage current-induced noise destroys the energy resolution of the detector.

Note that a 1 cm3 sample of pure germanium at 20 °C contains about 4.2×1022 atoms but also contains about 2.5 x 1013 free electrons and 2.5 x 1013 holes constantly generated from thermal energy. As can be seen, the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) would be minimal (compare it with 3 x 105 electron-hole pairs). Adding 0.001% of arsenic (an impurity) donates an extra 1017 free electrons in the same volume, and the electrical conductivity is increased by a factor of 10,000. The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) in doped material would be even smaller. Because germanium has a relatively low band gap, these detectors must be cooled to reduce the thermal generation of charge carriers (thus reverse leakage current) to an acceptable level. Otherwise, leakage current-induced noise destroys the energy resolution of the detector.

Reverse Biased Junction

The semiconductor detector operates much better as a radiation detector if an external voltage is applied across the junction in the reverse-biased direction. The depletion region will function as a radiation detector. Improvement can be achieved by using a reverse-bias voltage to the P-N junction to deplete the detector of free carriers, which is the principle of most semiconductor detectors. Reverse biasing a junction increases the thickness of the depletion region because the potential difference across the junction is enhanced. Germanium detectors have a p-i-n structure in which the intrinsic (i) region is sensitive to ionizing radiation, particularly X and gamma rays. Under reverse bias, an electric field extends across the intrinsic or depleted region. In this case, a negative voltage is applied to the p-side and positive to the second one. Holes in the p-region are attracted from the junction towards the p contact and similarly for electrons and the n contact. In proportion to the energy deposited in the detector by the incoming photon, this charge is converted into a voltage pulse by an integral charge-sensitive preamplifier.

See also: Germanium Detectors, MIRION Technologies. <available from: https://www.mirion.com/products/germanium-detectors>.

Application of Germanium Detectors – Gamma Spectroscopy

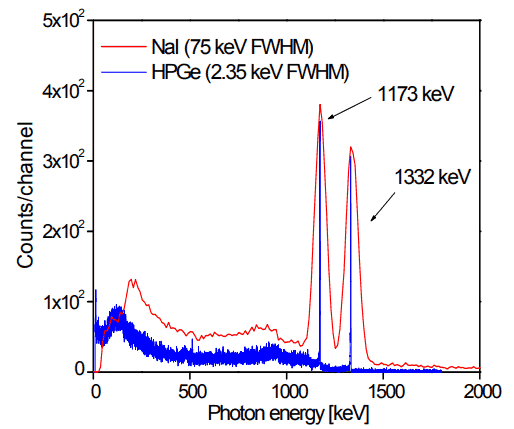

As was written, the study and analysis of gamma-ray spectra for scientific and technical use are called gamma spectroscopy. Gamma-ray spectrometers are the instruments that observe and collect such data. A gamma-ray spectrometer (GRS) is a sophisticated device for measuring the energy distribution of gamma radiation. For the measurement of gamma rays above several hundred keV, there are two detector categories of major importance, inorganic scintillators such as NaI(Tl) and semiconductor detectors. In the previous articles, we described gamma spectroscopy using a scintillation detector, which consists of a suitable scintillator crystal, a photomultiplier tube, and a circuit for measuring the height of the pulses produced by the photomultiplier. The advantages of a scintillation counter are its efficiency (large size and high density) and the possible high precision and counting rates. Due to the high atomic number of iodine, a large number of all interactions will result in complete absorption of gamma-ray energy so that the photo fraction will be high.

But if a perfect energy resolution is required, we must use a germanium-based detector, such as the HPGe detector. Germanium-based semiconductor detectors are most commonly used where a very good energy resolution is required, especially for gamma spectroscopy as well as x-ray spectroscopy. In gamma spectroscopy, germanium is preferred due to its atomic number being much higher than silicon, increasing the probability of gamma-ray interaction. Moreover, germanium has lower average energy necessary to create an electron-hole pair, which is 3.6 eV for silicon and 2.9 eV for germanium. This also provides the latter with a better resolution in energy. The FWHM (full width at half maximum) for germanium detectors is an energy function. For a 1.3 MeV photon, the FWHM is 2.1 keV, which is very low.