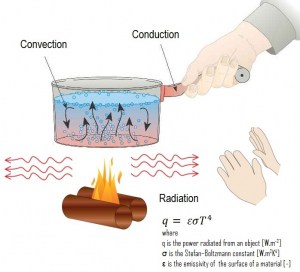

The term thermal radiation is frequently used to distinguish this form of electromagnetic radiation from other forms, such as radio waves, x-rays, or gamma rays.

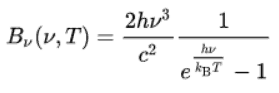

Radiation heat transfer rate, q [W/m2], from a body (e.g., a black body) to its surroundings is proportional to the fourth power of the absolute temperature. It can be expressed by the following equation:

q = εσT4

Thermal radiation is electromagnetic radiation in the infra-red region of the electromagnetic spectrum, although some of it is in the visible region. The term thermal radiation is frequently used to distinguish this form of electromagnetic radiation from other forms, such as radio waves, x-rays, or gamma rays. It is generated by the thermal motion of charged particles in matter, and therefore any material with a temperature above absolute zero gives off some radiant energy. Thermal radiation does not require any medium for energy transfer. Energy transfer by radiation is fastest (at the speed of light), and it suffers no attenuation in a vacuum.

In contrast to heat transfer by conduction or convection, which occurs in the direction of decreasing temperature, thermal radiation heat transfer can occur between two bodies separated by a medium colder than both bodies. For example, solar radiation reaches the surface of the earth after passing through cold layers of the atmosphere at high altitudes.

Stefan–Boltzmann Law

Radiation heat transfer rate, q [W/m2], from a body (e.g., a black body) to its surroundings is proportional to the fourth power of the absolute temperature. It can be expressed by the following equation:

q = εσT4

where σ is a fundamental physical constant called the Stefan–Boltzmann constant, equal to 5.6697×10-8 W/m2K4. The Stefan–Boltzmann constant is named after Josef Stefan (who discovered the Stefan-Boltzman law experimentally in 1879) and Ludwig Boltzmann (who derived it theoretically soon after). As can be seen, radiation heat transfer is important at very high temperatures and in a vacuum.

As was written, the Stefan–Boltzmann law gives the radiant intensity of a single object. But using the Stefan–Boltzmann law, we can also determine the radiation heat transfer between two objects. Two bodies that radiate toward each other have a net heat flux between them. The net flow rate of heat between them is given by:

Q = εσA1-2(T41 −T42) [J/s]

q = εσ(T41 −T42) [J/m2s]

The area factor A1-2 is the area viewed by body 2 of body 1 and can become fairly difficult to calculate.

Blackbody Radiation

It is known that the amount of radiation energy emitted from a surface at a given wavelength depends on the material of the body and the condition of its surface, as well as the surface temperature. Therefore, various materials emit different amounts of radiant energy even when they are at the same temperature. A body that emits the maximum amount of heat for its absolute temperature is called a blackbody.

A blackbody is an idealized physical body that has specific properties. By definition, a black body in thermal equilibrium has an emissivity of ε = 1.0. Real objects do not radiate as much heat as a perfect black body, and they radiate less heat than a black body and therefore are called gray bodies.

A blackbody is an idealized physical body that has specific properties. By definition, a black body in thermal equilibrium has an emissivity of ε = 1.0. Real objects do not radiate as much heat as a perfect black body, and they radiate less heat than a black body and therefore are called gray bodies.

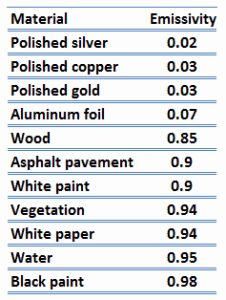

The surface of a blackbody emits thermal radiation at the rate of approximately 448 watts per square meter at room temperature (25 °C, 298.15 K). Real objects with emissivities less than 1.0 (e.g., copper wire) emit radiation at correspondingly lower rates (e.g., 448 x 0.03 = 13.4 W/m2). Emissivity plays an important role in heat transfer problems. For example, solar heat collectors incorporate selective surfaces with very low emissivities. These collectors waste very little of the solar energy through the emission of thermal radiation.

Since the absorptivity and the emissivity are interconnected by Kirchhoff’s Law of thermal radiation, a blackbody is also a perfect absorber of electromagnetic radiation.

Kirchhoff’s Law of thermal radiation:

For an arbitrary body emitting and absorbing thermal radiation in thermodynamic equilibrium, the emissivity is equal to the absorptivity.

A blackbody absorbs all incident electromagnetic radiation, regardless of frequency or angle of incidence, and its absorptivity is equal to unity, which is also the highest possible value. A blackbody is a perfect absorber (and a perfect emitter).

Note that visible radiation occupies a very narrow band of the spectrum from 400 to 760 nm. We cannot make any judgments about the blackness of a surface based on visual observations. For example, consider a white paper that reflects visible light and thus appears white. On the other hand, it is essentially black for infrared radiation (absorptivity α = 0.94) since they strongly absorb long-wavelength radiation.

See also: Ultraviolet Catastrophe

Spectrum – Thermal Radiation

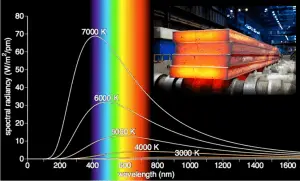

The Stefan–Boltzmann law determines the total blackbody emissive power, Eb, the sum of the radiation emitted over all wavelengths. Planck’s law describes the spectrum of blackbody radiation, which depends only on the object’s temperature and relates the spectral blackbody emissive power, Ebλ. This law is named after a German theoretical physicist Max Planck, who proposed it in 1900. Planck’s law is a pioneering result of modern physics and quantum theory. Planck’s hypothesis that energy is radiated and absorbed in discrete “quanta” (or energy packets) precisely matched the observed patterns of blackbody radiation and resolved the ultraviolet catastrophe.

Using this hypothesis, Planck showed that the spectral radiance of a body for frequency ν at absolute temperature T is given by:

- Bν(v, T) is the spectral radiance (the power per unit solid angle and per unit of area normal to the propagation) density of frequency ν radiation per unit frequency at thermal equilibrium at temperature T

- h is the Planck constant

- c is the speed of light in a vacuum

- kB is the Boltzmann constant

- ν is the frequency of the electromagnetic radiation

- T is the absolute temperature of the body

Planck’s law has the following important features:

- The emitted radiation varies continuously with wavelength.

- At any wavelength, the magnitude of the emitted radiation increases with increasing temperature.

- The spectral region where the radiation is concentrated depends on temperature, with comparatively more radiation appearing at shorter wavelengths as the temperature increases (Wien’s Displacement Law).