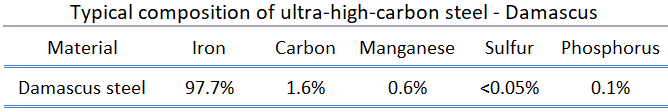

Ultra-high-carbon steel has approximately 1.25–2.0% carbon content. Steels that can be tempered to great hardness. This grade of steel could be used for hard steel products, such as truck springs, metal cutting tools, and other special purposes like (non-industrial-purpose) knives, axles, or punches. Most steels with more than 2.5% carbon content are made using powder metallurgy.

Ultra-high carbon steels (i.e., steels containing between 1 and 2.0% C and now known as UHCS) have extreme strength, sharpness, and resilience. The early use of steel compositions containing carbon contents above the eutectoid level is found in ancient weapons from around the world. For example, both Damascus and Japanese sword steels are hypereutectoid steels. The room temperature mechanical properties of the ultra-high-carbon steels exhibited a yield strength of 900 MPa and ultimate strength of 1100 MPa. This remarkable combination of strength and ductility confirms the general statements about ancient Damascus steels’ malleability.

Properties of Ultra-high-carbon Steel – Damascus Steel

Material properties are intensive properties, which means they are independent of the amount of mass and may vary from place to place within the system at any moment. Materials science involves studying materials’ structure and relating them to their properties (mechanical, electrical, etc.). Once materials scientist knows about this structure-property correlation, they can then go on to study the relative performance of a material in a given application. The major determinants of the structure of a material and thus of its properties are its constituent chemical elements and how it has been processed into its final form.

Mechanical Properties of Ultra-high-carbon Steel – Damascus Steel

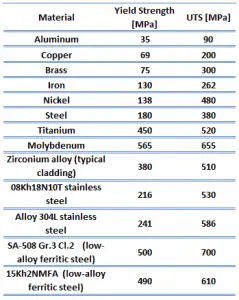

Materials are frequently chosen for various applications because they have desirable combinations of mechanical characteristics. For structural applications, material properties are crucial, and engineers must consider them.

Strength of Ultra-high-carbon Steel – Damascus Steel

In the mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. The strength of materials considers the relationship between the external loads applied to a material and the resulting deformation or change in material dimensions. The strength of a material is its ability to withstand this applied load without failure or plastic deformation.

Ultimate Tensile Strength

The ultimate tensile strength of ultra-high-carbon steel is 1100 MPa.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, a fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after achieving the ultimate strength. It is an intensive property; therefore, its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it depends on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steel.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, a fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after achieving the ultimate strength. It is an intensive property; therefore, its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it depends on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steel.

Yield Strength

The yield strength of ultra-high-carbon steel is 800 MPa.

The yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning plastic behavior. Yield strength or yield stress is the material property defined as the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically. In contrast, the yield point is the point where nonlinear (elastic + plastic) deformation begins. Before the yield point, the material will deform elastically and return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible. Some steels and other materials exhibit a behavior termed a yield point phenomenon. Yield strengths vary from 35 MPa for low-strength aluminum to greater than 1400 MPa for high-strength steel.

The hardness of Ultra-high-carbon Steel – Damascus Steel

Rockwell hardness of Damascus steel depends on the current type of the steel, but it may be approximately 62-64 HRC Rockwell.

Rockwell hardness test is one of the most common indentation hardness tests developed for hardness testing. In contrast to the Brinell test, the Rockwell tester measures the depth of penetration of an indenter under a large load (major load) compared to the penetration made by a preload (minor load). The minor load establishes the zero position, and the major load is applied, then removed while maintaining the minor load. The difference between the depth of penetration before and after application of the major load is used to calculate the Rockwell hardness number. That is, the penetration depth and hardness are inversely proportional. The chief advantage of Rockwell hardness is its ability to display hardness values directly. The result is a dimensionless number noted as HRA, HRB, HRC, etc., where the last letter is the respective Rockwell scale.