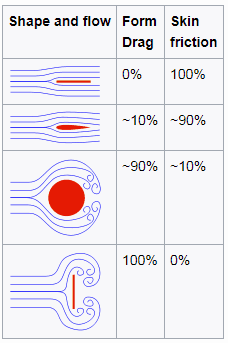

As was written, when a fluid flows over a stationary surface, e.g., the flat plate, the bed of a river, or the pipe wall, the fluid touching the surface is brought to rest by the shear stress at the wall. The boundary layer is the region in which flow adjusts from zero velocity at the wall to a maximum in the mainstream of the flow. Therefore, a moving fluid exerts tangential shear forces on the surface because of the no-slip condition caused by viscous effects. This type of drag force depends especially on the geometry, the roughness of the solid surface (only in turbulent flow), and the type of fluid flow.

The friction drag is proportional to the surface area. Therefore, bodies with a larger surface area will experience a larger friction drag. This is why commercial airplanes reduce their total surface area to save fuel. Friction drag is a strong function of viscosity, and an “idealized” fluid with zero viscosity would produce zero friction drag since the wall shear stress would be zero.

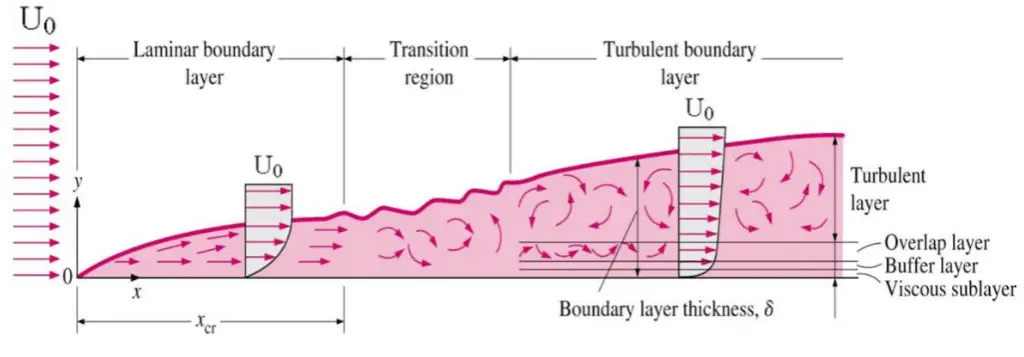

Skin friction is caused by viscous drag in the boundary layer around the object. Basic characteristics of all laminar and turbulent boundary layers are shown in the developing flow over a flat plate. The stages of the formation of the boundary layer are shown in the figure below:

Boundary layers may be either laminar or turbulent, depending on the value of the Reynolds number.

The boundary layer is laminar for lower Reynolds numbers, and the streamwise velocity changes uniformly as one moves away from the wall, as shown on the left side of the figure. As the Reynolds number increases (with x), the flow becomes unstable. Finally, the boundary layer is turbulent for higher Reynolds numbers, and the streamwise velocity is characterized by unsteady (changing with time) swirling flows inside the boundary layer.

The transition from laminar to turbulent boundary layer occurs when Reynolds number at x exceeds Rex ~ 500,000. The transition may occur earlier, but it is dependent especially on the surface roughness. The turbulent boundary layer thickens more rapidly than the laminar boundary layer due to increased shear stress at the body surface.

There are two ways to decrease friction drag:

- the first is to shape the moving body so that laminar flow is possible

- the second method is to increase the length and decrease the cross-section of the moving object as much as practicable.

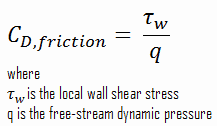

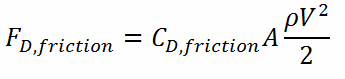

The skin friction coefficient, CD,friction, is defined by

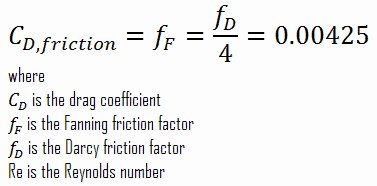

It must be noted the skin friction coefficient is equal to the Fanning friction factor. The Fanning friction factor, named after John Thomas Fanning, is a dimensionless number that is one-fourth of the Darcy friction factor. As can be seen, there is a connection between skin friction forces and frictional head losses.

See also: Darcy Friction Factor

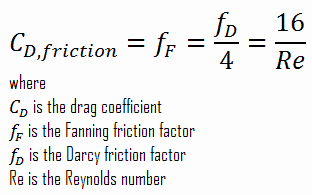

For laminar flow in a pipe, the Fanning friction factor (skin friction coefficient) is a consequence of Poiseuille’s law that and it is given by the following equations:

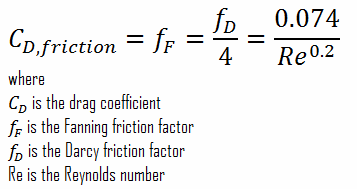

However, things are more difficult in turbulent flows, as the friction factor depends strongly on the pipe roughness. The friction factor for fluid flow can be determined using a Moody chart. For example:

The frictional component of the drag force is given by:

Calculation of the Skin Friction Coefficient

The friction factor for turbulent flow depends strongly on the relative roughness. It is determined by the Colebrook equation or can be determined using the Moody chart. The Moody chart for Re = 575 600 and ε/D = 5 x 10-4 returns following values:

- the Darcy friction factor is equal to fD = 0.017

- the Fanning friction factor is equal to fF = fD/4 = 0.00425

Therefore the skin friction coefficient is equal to: