Nuclear Fuel Breeding

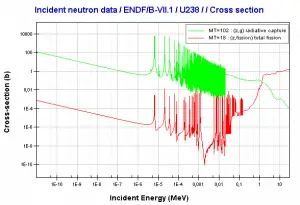

Fuel breeding or fuel conversion plays a significant role in the fuel cycle of all commercial power reactors. During fuel burnup, the fertile materials (conversion of 238U to fissile 239Pu known as fuel breeding) partially replace fissile 235U, thus permitting the power reactor to operate longer before the amount of fissile material decreases to the point where reactor criticality is no longer manageable.

It must be added natural uranium primarily consists of isotope 238U (99.28%). All commercial light water reactors contain both fissile and fertile materials. For example, most PWRs use low enriched uranium fuel with enrichment of 235U up to 5%. Therefore more than 95% of the content of fresh fuel is fertile isotope 238U.

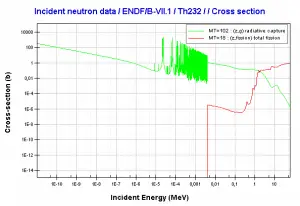

There is potential to increase the recoverable energy content from the world’s uranium and thorium resources by almost two orders of magnitude by converting the fertile isotopes uranium-238 and thorium-232 into fissile isotopes.

Conversion Factor – Breeding Ratio

A quantity that characterizes this conversion of fertile into fissile material is known as the conversion factor. The conversion factor is defined as the ratio of fissile material created to fissile material consumed either by fission or absorption. If the ratio is greater than one, it is often referred to as the breeding ratio, for then the reactor is creating more fissile material than it is consuming.

Comparison of cross-sections

Source: JANIS (Java-based nuclear information software) http://www.oecd-nea.org/janis/

Source: JANIS (Java-based nuclear information software)

http://www.oecd-nea.org/janis/

http://www.oecd-nea.org/janis/

When C is unity, one new atom is produced per one atom consumed. It seems fertile material can be converted in the reactor indefinitely without adding new fuel. Still, the content of fertile uranium 238 decreases in real reactors, and fission products with significant absorption cross-section accumulate in the fuel as fuel burnup increases.

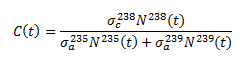

If we use a simplified model, which includes only uranium and plutonium-239, the conversion factor is:

This equation indicates that increased fuel enrichment results in a decreased value of C(0), the initial conversion factor. As the content of fissile material decreases with fuel burnup, the conversion factor increases. As this happens an increasing fraction of the fission comes from plutonium.

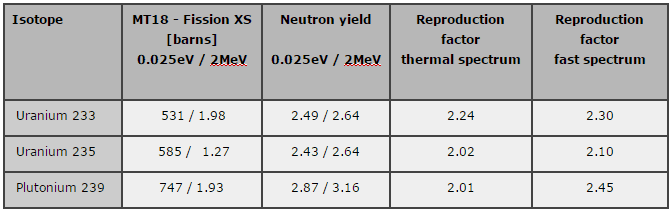

Conversion Factor and Excess of Neutrons

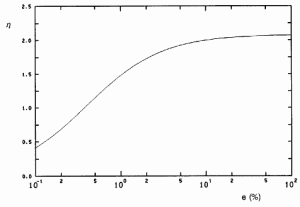

The role of the reproduction factor, η, is evident. The rate of transmutation of fertile-to-fissile isotopes depends on the number of neutrons more than those needed to maintain the chain fission reaction that is available. For conversion to occur, it is necessary that η must be greater than unity. Almost all reactors operate, at least to some extent, as converters. For fuel breeding to occur, it is necessary that η must be greater than 2. One neutron to sustain a chain reaction and one or more neutrons on average must be absorbed in fuel and must produce another fissile atom for natural uranium in the thermal reactor, η = 1.34. As a result of the ratios of the microscopic cross-sections, η increases strongly in the region of low enrichment fuels. This dependency is shown in the picture. It can be seen there is a limit value about η = 2.08.

The fertile-to-fissile conversion characteristics depend on the fuel cycle and the neutron energy spectrum. For a thermal neutron spectrum (E < 1 eV) and the uranium fuel cycle, fuel breeding (C>1) is not feasible, although η for both isotopes is greater than 2. This is due to the fact η is not large enough to compensate for the neutron leakage and its parasitic capture.

The situation is considerably better for a thermal neutron spectrum (E < 1 eV) and the thorium fuel cycle. Due to the very low capture-to-fission ratio, the reproduction factor for uranium 233 is about η = 2.25. From this point of view, is thorium fuel cycle is promising, and a thermal reactor of this type could successfully be made to breed.

For a fast neutron spectrum, there are differences in both the number of neutrons produced per one fission and, of course, in the capture-to-fission ratio, which is lower for fast reactors. The number of neutrons produced per one fission is also higher in fast reactors than in thermal reactors. These two features are important in the neutron economy and contribute to the fact that fast reactors have a large excess of neutrons in the core. The superior neutron economy of a fast neutron reactor makes it possible to build a reactor that, after its initial fuel charge of plutonium, requires only natural (or even depleted) uranium feedstock as input to its fuel cycle. Russian BN-350 liquid-metal-cooled reactor was operated with a breeding ratio of over 1.2.

Conversion Factor for LWRs

All commercial light water reactors breed fuel, but they have low breeding ratios. In recent years, the commercial power industry has emphasized high-burnup fuels (up to 60 – 70 GWd/tU), typically enriched to higher percentages of U-235 (up to 5%). As burnup increases, a higher percentage of the total power produced in a reactor is due to the fuel bred inside the reactor.

At a burnup of 30 GWd/tU (gigawatt-days per metric ton of uranium), about 30% of the total energy released comes from bred plutonium. At 40 GWd/tU, that percentage increases to about forty percent. This corresponds to a breeding ratio for these reactors of about 0.4 to 0.5. Light water reactors with higher fuel burnup (up to 60 GWd/tU) have a conversion ratio of approximately 0.6. That means about half of the fissile fuel in these reactors is bred there. This effect extends the cycle length for such fuels to nearly twice what it would otherwise be. MOX fuel has a smaller breeding effect than 235U fuel and is thus more challenging and slightly less economical to use due to a quick drop-off in reactivity through cycle life.

See also: High Burnup Fuel

Conversion Factor for Heavy-water Reactors

PHWRs (Pressurized Heavy Water Reactor) generally use natural uranium (0.7% U-235) or slightly enriched uranium oxide as fuel. Hence they need a more efficient moderator, in this case, heavy water (D2O) as was written, for natural uranium in the thermal reactor η = 1.34. Due to the favorable neutron management (very low parasitic capture) caused by online refueling and consequently reduced requirements for control poisons to compensate for excess reactivity, an application of natural uranium is possible, and these reactors attain a relatively high conversion factor of about 0.9.

Conversion Factor for Fast Reactors

As was written, the conversion factor in a light water reactor is about 0.5, i.e., the production of new nuclear fuel is much less than its consumption. This is caused, among other things, by the relatively low value of the neutron yield factor. For a fast neutron spectrum, there are differences in both the number of neutrons produced per one fission and, of course, in the capture-to-fission ratio, which is lower for fast reactors. The number of neutrons produced per one fission is also higher in fast reactors than in thermal reactors. These two features are important in the neutron economy and contribute to the fact that fast reactors have a large excess of neutrons in the core. The breeding ratio in these reactors can vary over a rather wide range, depending on the neutron energy spectrum. A large breeding ratio favors a hard neutron spectrum. The superior neutron economy of a fast neutron reactor makes it possible to build a reactor that, after its initial fuel charge of plutonium, requires only natural (or even depleted) uranium feedstock as input to its fuel cycle. Russian BN-350 liquid-metal-cooled reactor was operated with a breeding ratio of over 1.2.