The internal energy of n moles of an ideal monatomic (one atom per molecule) gas is equal to the average kinetic energy per molecule times the total number of molecules, N:

Eint = 3/2 NkT = 3/2 nRT

For diatomic ideal gas:

Eint = 5/2 NkT = 5/2 nRT

Internal energy is the total of all the energy associated with the motion of the atoms or molecules in the system. Microscopic forms of energy include those due to the rotation, vibration, translation, and interactions among the molecules of a substance.

Monatomic Gas – Internal Energy

For a monatomic ideal gas (such as helium, neon, or argon), the only contribution to the energy comes from translational kinetic energy. The average translational kinetic energy of a single atom depends only on the gas temperature and is given by the equation:

Kavg = 3/2 kT.

The internal energy of n moles of an ideal monatomic (one atom per molecule) gas is equal to the average kinetic energy per molecule times the total number of molecules, N:

Eint = 3/2 NkT = 3/2 nRT

where n is the number of moles, each direction (x, y, and z) contributes (1/2)nRT to the internal energy. This is where the equipartition of energy idea comes in – any other contribution to the energy must also contribute (1/2)nRT. As can be seen, the internal energy of an ideal gas depends only on temperature and the number of moles of gas.

Diatomic Molecule – Internal Energy

If the gas molecules contain more than one atom, there are three translation directions, and rotational kinetic energy contributes, but only for rotations about two of the three perpendicular axes. The five contributions to the energy (five degrees of freedom) give:

Diatomic ideal gas:

Eint = 5/2 NkT = 5/2 nRT

This is only an approximation and applies at intermediate temperatures. Only the translational kinetic energy contributes at low temperatures, and at higher temperatures, two additional contributions (kinetic and potential energy) come from vibration. The internal energy will be greater at a given temperature than for a monatomic gas, but it will still function only as temperature for an ideal gas.

The internal energy of real gases also depends mainly on temperature, but similarly, as the Ideal Gas Law, the internal energy of real gases depends also somewhat on pressure and volume. All real gases approach the ideal state at low pressures (densities). At low pressures, molecules are far enough apart that they do not interact with one another. The internal energy of liquids and solids is quite complicated, for it includes electrical potential energy associated with the forces (or chemical bonds) between atoms and molecules.

Specific Heat at Constant Volume and Constant Pressure

Specific heat is a property related to internal energy that is very important in thermodynamics. The intensive properties cv and cp are defined for pure, simple compressible substances as partial derivatives of the internal energy u(T, v) and enthalpy h(T, p), respectively:

where the subscripts v and p denote the variables held fixed during differentiation. The properties cv and cp are referred to as specific heats (or heat capacities). Under certain special conditions, they relate the temperature change of a system to the amount of energy added by heat transfer. Their SI units are J/kg K, or J/mol K. Two specific heats are defined for gases, constant volume (cv), and constant pressure (cp).

According to the first law of thermodynamics, for a constant volume process with a monatomic ideal gas, the molar specific heat will be:

According to the first law of thermodynamics, for a constant volume process with a monatomic ideal gas, the molar specific heat will be:

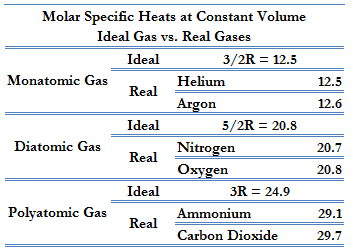

Cv = 3/2R = 12.5 J/mol K

because

U = 3/2nRT

It can be derived that the molar specific heat at constant pressure is:

Cp = Cv + R = 5/2R = 20.8 J/mol K

This Cp is greater than the molar specific heat at constant volume Cv because energy must now be supplied not only to raise the temperature of the gas but also for the gas to do work because, in this case, volume changes.