In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, abrasion, indentation, or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

There are three main types of hardness measurements:

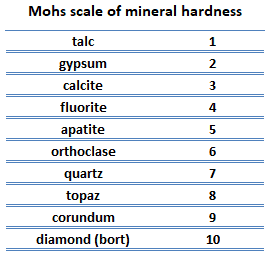

Scratch hardness. Scratch hardness measures how resistant a sample is to permanent plastic deformation due to friction from a sharp object. The most common scale for this qualitative test is the Mohs scale, which is used in mineralogy. The Mohs scale of mineral hardness is based on the ability of one natural sample of mineral to scratch another mineral visibly. The hardness of a material is measured against the scale by finding the hardest material that the given material can scratch or the softest material that can scratch the given material. For example, if some material is scratched by topaz but not by quartz, its hardness on the Mohs scale would fall between 7 and 8.

Scratch hardness. Scratch hardness measures how resistant a sample is to permanent plastic deformation due to friction from a sharp object. The most common scale for this qualitative test is the Mohs scale, which is used in mineralogy. The Mohs scale of mineral hardness is based on the ability of one natural sample of mineral to scratch another mineral visibly. The hardness of a material is measured against the scale by finding the hardest material that the given material can scratch or the softest material that can scratch the given material. For example, if some material is scratched by topaz but not by quartz, its hardness on the Mohs scale would fall between 7 and 8.- Indentation hardness. Indentation hardness measures the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and the resistance of a sample to material deformation due to a constant compression load from a sharp object. Tests for indentation hardness are primarily used in engineering and metallurgy fields. The traditional methods are based on well-defined physical indentation hardness tests. Very hard indenters of defined geometries and sizes are continuously pressed into the material under a particular force. Deformation parameters, such as the indentation depth in the Rockwell method, are recorded to give measures of hardness. Common indentation hardness scales are Brinell, Rockwell and Vickers.

- Rebound hardness. Rebound hardness, also known as dynamic hardness, measures the height of the “bounce” of a diamond-tipped hammer dropped from a fixed height onto a material. One of the devices used to take this measurement is known as a scleroscope, consisting of a steel ball dropped from a fixed height. This type of hardness is related to elasticity.

Within each of these classes of measurement, there are individual measurement scales. For practical reasons, conversion tables convert between one scale and another.

Measuring Hardness

Many techniques have been developed for obtaining a qualitative and quantitative measure of hardness. Among the most popular are indentation tests, which are based on the ability of a material to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation). Brinell, Rockwell, Vickers, Tukon, Sclerscope, and the Leeb rebound hardness test are most often used. The first four are based on indentation tests, and the fifth on the rebound height of a diamond-tipped metallic hammer. According to the dynamic Leeb principle, the hardness value is derived from the energy loss of a defined impact body after impacting a metal sample, similar to the Shore scleroscope. As a result of many tests, comparisons have been prepared using formulas, tables, and graphs that show the relationships between the results of various hardness tests of specific alloys. However, there is no exact mathematical relation between any two methods.

Brinell Hardness Test

Brinell hardness test is one of the indentation hardness tests developed for hardness testing. In Brinell tests, a hard, spherical indenter is forced under a specific load into the surface of the metal to be tested. The typical test uses a 10 mm (0.39 in) diameter hardened steel ball as an indenter with a 3,000 kgf (29.42 kN; 6,614 lbf) force. The load is maintained constant for a specified time (between 10 and 30 s). A smaller force is used; a tungsten carbide ball is substituted for the steel ball for harder materials.

The test provides numerical results to quantify the hardness of a material, which is expressed by the Brinell hardness number – HB. The Brinell hardness number is designated by the most commonly used test standards (ASTM E10-14[2] and ISO 6506–1:2005) as HBW (H from hardness, B from Brinell, and W from the material of the indenter, tungsten (wolfram) carbide). In former standards, HB or HBS were used to refer to measurements made with steel indenters.

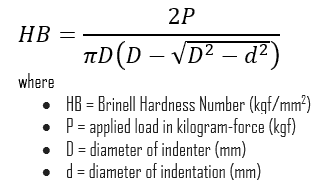

The Brinell hardness number (HB) is the load divided by the surface area of the indentation. The diameter of the impression is measured with a microscope with a superimposed scale. The Brinell hardness number is computed from the equation:

There are various test methods in common use (e.g., Brinell, Knoop, Vickers, and Rockwell). Some tables correlate the hardness numbers from the different test methods where correlation is applicable. In all scales, a high hardness number represents a hard metal.

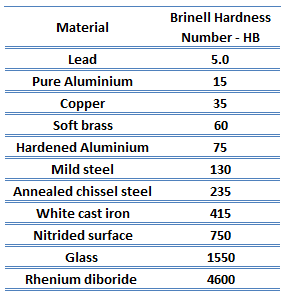

Besides the correlation between different hardness numbers, some correlations are possible with other material properties. For example, another convenient conversion is Brinell hardness to ultimate tensile strength for heat-treated plain carbon steels and medium alloy steels. In this case, the ultimate tensile strength (in psi) approximately equals the Brinell Hardness Number multiplied by 500. Generally, a high hardness will indicate a relatively high strength and low ductility in the material.

Besides the correlation between different hardness numbers, some correlations are possible with other material properties. For example, another convenient conversion is Brinell hardness to ultimate tensile strength for heat-treated plain carbon steels and medium alloy steels. In this case, the ultimate tensile strength (in psi) approximately equals the Brinell Hardness Number multiplied by 500. Generally, a high hardness will indicate a relatively high strength and low ductility in the material.

In industry, hardness tests on metals are used mainly as a check on the quality and uniformity of metals, especially during heat treatment operations. The tests can generally be applied to the finished product without significant damage.

Rockwell Hardness Test

Rockwell hardness test is one of the most common indentation hardness tests developed for hardness testing. In contrast to the Brinell test, the Rockwell tester measures the depth of penetration of an indenter under a large load (major load) compared to the penetration made by a preload (minor load). The minor load establishes the zero position, and the major load is applied, then removed while maintaining the minor load. The difference between the depth of penetration before and after application of the major load is used to calculate the Rockwell hardness number. That is, the penetration depth and hardness are inversely proportional. The chief advantage of Rockwell hardness is its ability to display hardness values directly. The result is a dimensionless number noted as HRA, HRB, HRC, etc., where the last letter is the respective Rockwell scale.

Several different scales may be used from possible combinations of various indenters and different loads, a process that permits virtually testing all metal alloys. The test provides results to quantify the hardness of a material, which is expressed by the Rockwell hardness number – HR, which is directly displayed on the dial. The various indenter types combined with a range of test loads form a matrix of Rockwell hardness scales that apply to various materials. Rockwell B and Rockwell C are the typical tests in this facility. The Rockwell B penetrator is a 1.59mm (1/16 inch) diameter tungsten-carbide ball, and the major load is 100kg. The Rockwell C test is performed with a Brale penetrator (120°diamond cone) and a major load of 150kg.

Each Rockwell hardness scale is identified by a letter designation indicative of the indenter type and the major and minor loads used for the test. The Rockwell hardness number is expressed as a combination of the measured numerical hardness value and the scaling letter preceded by the letters HR.

Various hardness test methods are in common use (e.g., Brinell, Knoop, Vickers, and Rockwell). Some tables correlate the hardness numbers from the different test methods where correlation is applicable. In all scales, a high hardness number represents a hard metal.

In industry, hardness tests on metals are used mainly as a check on the quality and uniformity of metals, especially during heat treatment operations. The tests can generally be applied to the finished product without significant damage. The commercial popularity of the Rockwell hardness test arises from its speed, reliability, robustness, resolution, and a small area of indentation.

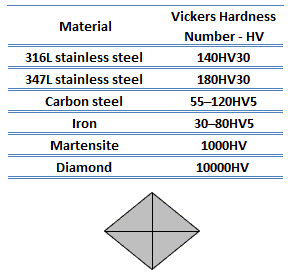

Vickers Hardness Test

The Vickers hardness test method was developed by Robert L. Smith and George E. Sandland at Vickers Ltd as an alternative to the Brinell method to measure the hardness of materials. The Vickers hardness test method can also be used as a microhardness test method, mostly for small parts, thin sections, or case depth work. Since the test indentation is very small in a Vickers microhardness test, it is useful for a variety of applications such as: testing very thin materials like foils or measuring the surface of a part, small parts, or small areas.

The Vickers hardness test method was developed by Robert L. Smith and George E. Sandland at Vickers Ltd as an alternative to the Brinell method to measure the hardness of materials. The Vickers hardness test method can also be used as a microhardness test method, mostly for small parts, thin sections, or case depth work. Since the test indentation is very small in a Vickers microhardness test, it is useful for a variety of applications such as: testing very thin materials like foils or measuring the surface of a part, small parts, or small areas.

The Vickers method is based on an optical measurement system. The Microhardness test procedure, ASTM E-384, specifies a range of light loads using a diamond indenter to make an indentation which is measured and converted to a hardness value. The Vickers test is often easier to use than other hardness tests since the required calculations are independent of the size of the indenter, and the indenter can be used for all materials irrespective of hardness. A square base pyramid-shaped diamond is used for testing in the Vickers scale. For micro-indentation, typical loads are very light, ranging from 10gf to 1kgf, although macro-indentation Vickers loads can range up to 30 kg or more.

Knoop Hardness Test

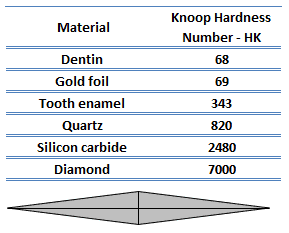

The Knoop hardness test method is one of the micro-hardness tests – tests for mechanical hardness used particularly for very brittle materials or thin sheets, where only a small indentation may be made for testing purposes. The Knoop and Vickers techniques are called micro-indentation-testing methods based on indenter size. Both are well suited for measuring the hardness of small, selected specimen regions; furthermore, the Knoop technique is used for testing brittle materials such as ceramics. The geometry of this indenter is an extended pyramid with the length to width ratio being 7:1, and respective face angles are 172 degrees for the long edge and 130 degrees for the short edge.

The Knoop hardness test method is one of the micro-hardness tests – tests for mechanical hardness used particularly for very brittle materials or thin sheets, where only a small indentation may be made for testing purposes. The Knoop and Vickers techniques are called micro-indentation-testing methods based on indenter size. Both are well suited for measuring the hardness of small, selected specimen regions; furthermore, the Knoop technique is used for testing brittle materials such as ceramics. The geometry of this indenter is an extended pyramid with the length to width ratio being 7:1, and respective face angles are 172 degrees for the long edge and 130 degrees for the short edge.

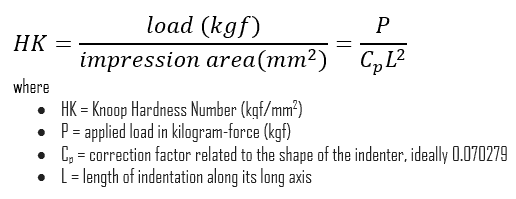

The Knoop and Vickers hardness numbers are designated by HK and HV, respectively, and hardness scales for both techniques are approximately equivalent. The Knoop hardness number HK is given by the formula:

Hardness Numbers and Conversion

Various hardness test methods are in common use (e.g., Brinell, Knoop, Vickers, and Rockwell). Some tables correlate the hardness numbers from the different test methods where correlation is applicable. In all scales, a high hardness number represents a hard metal.

In industry, hardness tests on metals are used mainly as a check on the quality and uniformity of metals, especially during heat treatment operations. The tests can generally be applied to the finished product without significant damage. The commercial popularity of the Rockwell hardness test arises from its speed, reliability, robustness, resolution, and a small area of indentation.

Hardness and Tensile Strength

Besides the correlation between different hardness numbers, some correlations are possible with other material properties. For example, another convenient conversion is Brinell hardness to ultimate tensile strength for heat-treated plain carbon steels and medium alloy steels. In this case, the ultimate tensile strength (in psi) approximately equals the Brinell Hardness Number multiplied by 500. Generally, a high hardness will indicate a relatively high strength and low ductility in the material.

In industry, hardness tests on metals are used mainly as a check on the quality and uniformity of metals, especially during heat treatment operations. The tests can generally be applied to the finished product without significant damage.