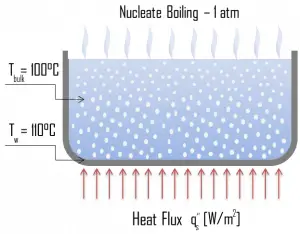

Nucleate boiling significantly improves the ability of a surface to transfer thermal energy to the bulk fluid.

The nucleate boiling heat flux cannot be increased indefinitely. At some value, we call it the “critical heat flux”, the steam produced can form an insulating layer over the surface, which in turn deteriorates the heat transfer coefficient.

The most common type of local boiling encountered in nuclear facilities is nucleate boiling. But in the case of nuclear reactors, nucleate boiling occurs at significant flow rates through the reactor. In nucleate boiling, steam bubbles form at the heat transfer surface and then break away and are carried into the mainstream of the fluid. Such movement enhances heat transfer because the heat generated at the surface is carried directly into the fluid stream. Once in the main fluid stream, the bubbles collapse because the bulk temperature of the fluid is not as high as the heat transfer surface temperature where the bubbles were created.

As was written, nucleate boiling at the surface effectively disrupts this stagnant layer. Therefore, nucleate boiling significantly improves the ability of a surface to transfer thermal energy to the bulk fluid. This heat transfer process is sometimes desirable because the energy created at the heat transfer surface is quickly and efficiently “carried” away.

As was written, nucleate boiling at the surface effectively disrupts this stagnant layer. Therefore, nucleate boiling significantly improves the ability of a surface to transfer thermal energy to the bulk fluid. This heat transfer process is sometimes desirable because the energy created at the heat transfer surface is quickly and efficiently “carried” away.

Close to the wall, the situation is complex for several mechanisms increase the heat flux above that for pure conduction through the liquid.

- Note that, even in turbulent flow, there is a stagnant fluid film layer (laminar sublayer) that isolates the surface of the heat exchanger. The upward flux (due to buoyant forces) of vapor away from the wall must be balanced by an equal mass flux of liquid, and this brings cooler liquid into closer proximity to the wall.

- The formation and movement of the bubbles turbulises the liquid near the wall and thus increases heat transfer from the wall to the liquid.

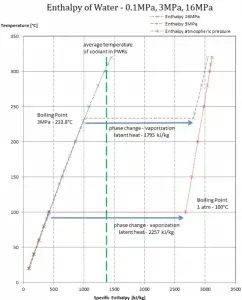

- Boiling differs from other forms of convection in that it depends on the latent heat of vaporization, which is very high for common pressures. Therefore large amounts of heat can be transferred during boiling essentially at a constant temperature.

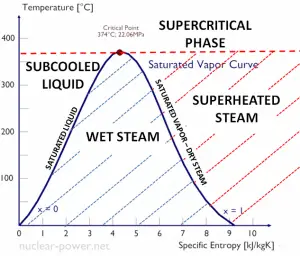

The nucleate boiling heat flux cannot be increased indefinitely. We call it the “critical heat flux” (CHF) at some value. The steam produced can form an insulating layer over the surface, which in turn deteriorates the heat transfer coefficient. This is because a large fraction of the surface is covered by a vapor film, which acts as thermal insulation due to the low thermal conductivity of the vapor relative to that of the liquid. Immediately after the critical heat flux has been reached, boiling becomes unstable, and transition boiling occurs. The transition from nucleate boiling to film boiling is known as the “boiling crisis”. Since the heat transfer coefficient decreases beyond the CHF point, the transition to film boiling is usually inevitable.

The nucleate boiling heat flux cannot be increased indefinitely. We call it the “critical heat flux” (CHF) at some value. The steam produced can form an insulating layer over the surface, which in turn deteriorates the heat transfer coefficient. This is because a large fraction of the surface is covered by a vapor film, which acts as thermal insulation due to the low thermal conductivity of the vapor relative to that of the liquid. Immediately after the critical heat flux has been reached, boiling becomes unstable, and transition boiling occurs. The transition from nucleate boiling to film boiling is known as the “boiling crisis”. Since the heat transfer coefficient decreases beyond the CHF point, the transition to film boiling is usually inevitable.

In the following section, we will distinguish between:

- nucleate pool boiling

- nucleate flow boiling

Nucleate Boiling Correlations – Pool Boiling

The boiling regimes discussed above differ considerably in their character, and different correlations describe heat transfer. This section reviews some of the more widely used correlations for nucleate boiling.

Nucleate Pool Boiling

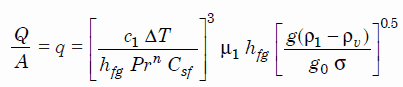

Rohsenow correlation

The most widely used correlation for the rate of heat transfer in the nucleate pool boiling was proposed in 1952 by Rohsenow:

Rohsenow correlation

where

- q – nucleate pool boiling heat flux [W/m2]

- c1 — specific heat of liquid J/kg K

- ΔT — excess temperature °C or K

- hfg – enthalpy of vaporization, J/kg

- Pr — Prandtl number of liquid

- n — experimental constant equal to 1 for water and 1.7 for other fluids

- Csf — surface fluid factor, for example, water and nickel have a Csf of 0.006

- μ1 — dynamic viscosity of the liquid kg/m.s

- g – gravitational acceleration m/s2

- g0 — force conversion factor kgm/Ns2

- ρ1 — density of the liquid kg/m3

- ρv — density of vapor kg/m3

- σ — surface tension-liquid-vapor interface N/m

As can be seen, ΔT ∝ (q)⅓. This very important proportionality shows the increasing ability of the interface to transfer heat.

Nucleate Boiling – Flow Boiling

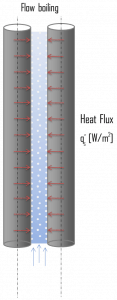

In flow boiling (or forced convection boiling), fluid flow is forced over a surface by external means such as a pump, as well as by buoyancy effects. Therefore, flow boiling is always accompanied by other convection effects. Conditions depend strongly on geometry, involving external flow over heated plates and cylinders or internal (duct) flow. In nuclear reactors, most boiling regimes are just forced convection boiling. The flow boiling is also classified as either external and internal flow boiling, depending on whether the fluid is forced to flow over a heated surface or inside a heated channel.

In flow boiling (or forced convection boiling), fluid flow is forced over a surface by external means such as a pump, as well as by buoyancy effects. Therefore, flow boiling is always accompanied by other convection effects. Conditions depend strongly on geometry, involving external flow over heated plates and cylinders or internal (duct) flow. In nuclear reactors, most boiling regimes are just forced convection boiling. The flow boiling is also classified as either external and internal flow boiling, depending on whether the fluid is forced to flow over a heated surface or inside a heated channel.

Internal flow boiling is much more complicated in nature than external flow boiling because there is no free surface for the vapor to escape, and thus both the liquid and the vapor are forced to flow together. The two-phase flow in a tube exhibits different flow boiling regimes, depending on the relative amounts of the liquid and the vapor phases. Therefore internal forced convection boiling is commonly referred to as two-phase flow.

Nucleate Boiling Correlations – Flow Boiling

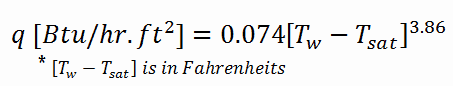

McAdams Correlation

In fully developed nucleate boiling with saturated coolant, the wall temperature is determined by local heat flux and pressure and is only slightly dependent on the Reynolds number. For subcooled water at absolute pressures between 0.1 – 0.6 MPa, McAdams correlation gives:

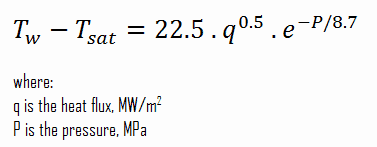

Thom Correlation

The Thom correlation is for the flow boiling (subcooled or saturated at pressures up to about 20 MPa) under conditions where the nucleate boiling contribution predominates over forced convection. This correlation is useful for a rough estimation of expected temperature difference given the heat flux:

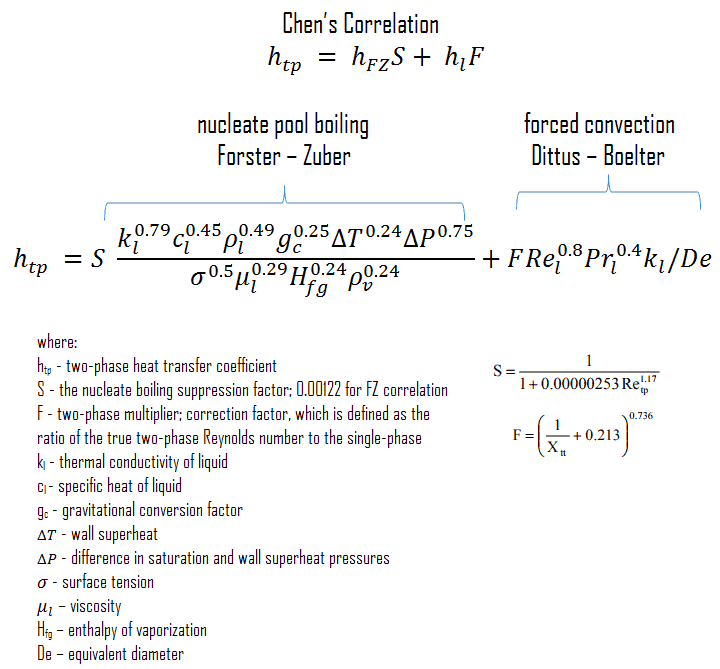

Chen’s Correlation

In 1963, Chen proposed the first flow boiling correlation for evaporation in vertical tubes to attain widespread use. Chen’s correlation includes both the heat transfer coefficients due to nucleate boiling as well as forced convective mechanisms. It must be noted at higher vapor fractions. The heat transfer coefficient varies strongly with the flow rate, and the flow velocity in a core can be very high, causing very high turbulences. This heat transfer mechanism has been referred to as “forced convection evaporation”. No adequate criteria have been established to determine the transition from nucleate boiling to forced convection vaporization. However, a single correlation that is valid for both nucleate boiling and forced convection vaporization has been developed by Chen for saturated boiling conditions and extended to include subcooled boiling by others. Chen proposed a correlation where the heat transfer coefficient is the sum of a forced convection component and a nucleate boiling component. It must be noted the nucleate pool boiling correlation of Forster and Zuber (1955) is used to calculate the nucleate boiling heat transfer coefficient, hFZ, and the turbulent flow correlation of Dittus-Boelter (1930) is used to calculate the liquid-phase convective heat transfer coefficient, hl.

The nucleate boiling suppression factor, S, is the ratio of the effective superheats to wall superheat. It accounts for decreased boiling heat transfer because the effective superheat across the boundary layer is less than the superheat based on wall temperature. The two-phase multiplier, F, is a function of the Martinelli parameter χtt.

Boiling Crisis – Critical Heat Flux

As was written, in nuclear reactors, limitations of the local heat flux are of the highest importance for reactor safety. For pressurized water reactors and boiling water reactors, there are thermal-hydraulic phenomena, which cause a sudden decrease in heat transfer efficiency (more precisely in the heat transfer coefficient). These phenomena occur at a certain value of heat flux, known as the “critical heat flux”. The phenomena that cause heat transfer deterioration are different for PWRs and BWRs.

As was written, in nuclear reactors, limitations of the local heat flux are of the highest importance for reactor safety. For pressurized water reactors and boiling water reactors, there are thermal-hydraulic phenomena, which cause a sudden decrease in heat transfer efficiency (more precisely in the heat transfer coefficient). These phenomena occur at a certain value of heat flux, known as the “critical heat flux”. The phenomena that cause heat transfer deterioration are different for PWRs and BWRs.

In both types of reactors, the problem is more or less associated with departure from nucleate boiling. The nucleate boiling heat flux cannot be increased indefinitely, and we call it the “critical heat flux” (CHF) at some value. The steam produced can form an insulating layer over the surface, which in turn deteriorates the heat transfer coefficient. Immediately after the critical heat flux has been reached, boiling becomes unstable, and film boiling occurs. The transition from nucleate boiling to film boiling is known as the “boiling crisis”. As was written, the phenomena that cause heat transfer deterioration are different for PWRs and BWRs.

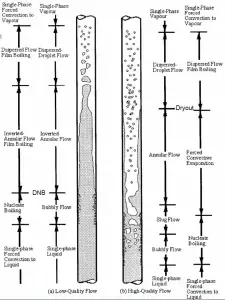

Departure From Nucleate Boiling – DNB

In the case of PWRs, the critical safety issue is named DNB (departure from nucleate boiling), which causes the formation of a local vapor layer, causing a dramatic reduction in heat transfer capability. This phenomenon occurs in the subcooled or low-quality region. The behavior of the boiling crisis depends on many flow conditions (pressure, temperature, flow rate). Still, the boiling crisis occurs at relatively high heat fluxes and appears to be associated with the cloud of bubbles adjacent to the surface. These bubbles or films of vapor reduce the amount of incoming water. Since this phenomenon deteriorates the heat transfer coefficient and the heat flux remains, heat accumulates in the fuel rod, causing a dramatic rise in cladding and fuel temperature. Simply, a very high-temperature difference is required to transfer the critical heat flux produced from the fuel rod’s surface to the reactor coolant (through the vapor layer).

In the case of PWRs, the critical safety issue is named DNB (departure from nucleate boiling), which causes the formation of a local vapor layer, causing a dramatic reduction in heat transfer capability. This phenomenon occurs in the subcooled or low-quality region. The behavior of the boiling crisis depends on many flow conditions (pressure, temperature, flow rate). Still, the boiling crisis occurs at relatively high heat fluxes and appears to be associated with the cloud of bubbles adjacent to the surface. These bubbles or films of vapor reduce the amount of incoming water. Since this phenomenon deteriorates the heat transfer coefficient and the heat flux remains, heat accumulates in the fuel rod, causing a dramatic rise in cladding and fuel temperature. Simply, a very high-temperature difference is required to transfer the critical heat flux produced from the fuel rod’s surface to the reactor coolant (through the vapor layer).

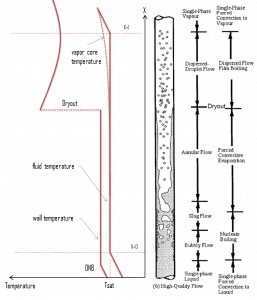

In the case of PWRs, the critical flow is inverted annular flow, while in BWRs, the critical flow is usually annular flow. The difference in flow regime between post-dry-out flow and post-DNB flow is depicted in the figure. In PWRs at normal operation, the flow is considered to be single-phase. But a great deal of study has been performed on the nature of two-phase flow in case of transients and accidents (such as the loss-of-coolant accident – LOCA or trip of RCPs), which are of importance in reactor safety and in must be proved and declared in the Safety Analysis Report (SAR).

One of the key safety requirements of pressurized water reactors is that a departure from nucleate boiling (DNB) will not occur during steady-state operation, normal operational transients, and anticipated operational occurrences (AOOs). Fuel cladding integrity will be maintained if the minimum DNBR remains above the 95/95 DNBR limit for PWRs ( a 95% probability at a 95% confidence level). DNB criterion is one of the acceptance criteria in safety analyses as well as it constitutes one of the safety limits in technical specifications.

Dryout – BWRs

In BWRs, a similar phenomenon is known as “dry out,” and it is directly associated with changes in flow pattern during evaporation in the high-quality region. At given combinations of flow rate through a channel, pressure, flow quality, and linear heat rate, the liquid wall film may exhaust, and the wall may be dried out. At normal, the fuel surface is effectively cooled by boiling coolant. However, when the heat flux exceeds a critical value (CHF – critical heat flux), the flow pattern may reach the dry-out conditions (a thin film of liquid disappears). The heat transfer from the fuel surface into the coolant is deteriorated due to a drastically increased fuel surface temperature. In the high-quality region, the crisis occurs at a lower heat flux. Since the flow velocity in the vapor core is high, post-CHF heat transfer is much better than low-quality critical flux (i.e., for PWRs, temperature rises are higher and more rapid).

In BWRs, a similar phenomenon is known as “dry out,” and it is directly associated with changes in flow pattern during evaporation in the high-quality region. At given combinations of flow rate through a channel, pressure, flow quality, and linear heat rate, the liquid wall film may exhaust, and the wall may be dried out. At normal, the fuel surface is effectively cooled by boiling coolant. However, when the heat flux exceeds a critical value (CHF – critical heat flux), the flow pattern may reach the dry-out conditions (a thin film of liquid disappears). The heat transfer from the fuel surface into the coolant is deteriorated due to a drastically increased fuel surface temperature. In the high-quality region, the crisis occurs at a lower heat flux. Since the flow velocity in the vapor core is high, post-CHF heat transfer is much better than low-quality critical flux (i.e., for PWRs, temperature rises are higher and more rapid).

The change from the liquid to the vapor state due to boiling is sustained by heat transfer from the solid surface; conversely, condensation of a vapor to the liquid state results in heat transfer to the solid surface. Boiling and condensation differ from other forms of convection in that they depend on the latent heat of vaporization, which is very high for common

The change from the liquid to the vapor state due to boiling is sustained by heat transfer from the solid surface; conversely, condensation of a vapor to the liquid state results in heat transfer to the solid surface. Boiling and condensation differ from other forms of convection in that they depend on the latent heat of vaporization, which is very high for common