A simple point dynamics model is based on point kinetics equations, but here we should take into account the influence of the fuel and the moderator temperature on the reactivity.

The reactivity feedbacks and their time constants are a very important area of reactor design because they determine the stability of the reactor.

Clearly, a reactor with negative αT is inherently stable to changes in its temperature and thermal power, while a reactor with positive αT is inherently unstable.

In the preceding chapter (Nuclear Chain Reaction), the classification of states of a reactor according to the effective multiplication factor – keff was introduced. The effective multiplication factor – keff is a measure of the change in the fission neutron population from one neutron generation to the subsequent generation. Also, reactivity as a measure of a reactor’s relative departure from criticality was defined.

In this section, amongst other things, we will briefly describe how the neutron flux (i.e., the reactor power) changes if the reactivity of a multiplying system is not equal to zero. We will study the time-dependent behavior of nuclear reactors. Understanding the time-dependent behavior of the neutron population in a nuclear reactor in response to either a planned change in the reactor’s reactivity or to unplanned and abnormal conditions is very important for nuclear reactor safety.

Reactor Kinetics vs. Reactor Dynamics

This chapter is named the Reactor Dynamics but also comprises the reactor kinetics. Nuclear reactor kinetics deals with transient neutron flux changes resulting from a departure from the critical state, from some reactivity insertion. Such situations arise during operational changes such as control rods motion, environmental changes such as a change in boron concentration, or accidental disturbances in the reactor steady-state operation.

In general:

- Reactor Kinetics. Reactor kinetics is the study of the time-dependence of the neutron flux for postulated changes in the macroscopic cross-sections. It is also referred to as reactor kinetics without feedbacks.

- Reactor Dynamics. Reactor dynamics is the study of the time-dependence of the neutron flux when the macroscopic cross-sections are allowed to depend in turn on the neutron flux level. It is also referred to as reactor kinetics with feedbacks and with spatial effects.

The time-dependent behavior of nuclear reactors can also be classified by the time scale as:

- Short-term kinetics describes phenomena that occur over times shorter than a few seconds. This comprises the response of a reactor to either a planned change in the reactivity or to unplanned and abnormal conditions. In this section, we will introduce especially point kinetics equations.

- Medium-term kinetics describes phenomena that occur for several hours to a few days. This comprises especially effects of neutron poisons on the reactivity (i.e., Xenon poisoning or spatial oscillations).

- Long-term kinetics describes phenomena that occur over months or even years. This comprises all long-term changes in fuel composition as a result of fuel burnup.

This chapter is concerned with short-, medium- and long-term kinetics, despite the fact the fuel burnup and other changes in fuel composition are usually not a dynamic problem. At first, we have to start with an introduction to prompt and delayed neutrons because they play an important role in short-term reactor kinetics. Despite the fact, the number of delayed neutrons per fission neutron is quite small (typically below 1%) and thus does not contribute significantly to the power generation, they play a crucial role in the reactor control and are essential from the point of view of reactor kinetics and reactor safety. Their presence completely changes the dynamic time response of a reactor to some reactivity change, making it controllable by control systems such as the control rods.

Prompt and Delayed Neutrons

It is known that fission neutrons are of importance in any chain-reacting system. Neutrons trigger the nuclear fission of some nuclei (235U, 238U, or even 232Th). What is crucial the fission of such nuclei produces 2, 3, or more free neutrons.

But not all neutrons are released at the same time following fission. Even the nature of the creation of these neutrons is different. From this point of view, we usually divide the fission neutrons into two following groups:

- Prompt Neutrons. Prompt neutrons are emitted directly from fission, and they are emitted within a very short time of about 10-14 seconds.

- Delayed Neutrons. Delayed neutrons are emitted by neutron-rich fission fragments that are called delayed neutron precursors. These precursors usually undergo beta decay, but a small fraction of them are excited enough to undergo neutron emission. The fact the neutron is produced via this type of decay, and this happens orders of magnitude later compared to the emission of the prompt neutrons, plays an extremely important role in the control of the reactor.

Key Characteristics of Prompt Neutrons

- Prompt neutrons are emitted directly from fission, and they are emitted within a very short time of about 10-14 seconds.

- Most of the neutrons produced in fission are prompt neutrons – about 99.9%.

- For example, fission of 235U by thermal neutron yields 2.43 neutrons, of which 2.42 neutrons are prompt neutrons, and 0.01585 neutrons are the delayed neutrons.

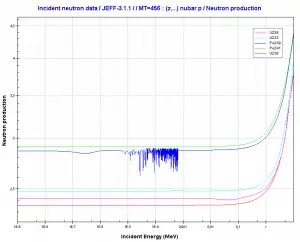

- The production of prompt neutrons slightly increases with incident neutron energy.

- Almost all prompt fission neutrons have energies between 0.1 MeV and 10 MeV.

- The mean neutron energy is about 2 MeV. The most probable neutron energy is about 0.7 MeV.

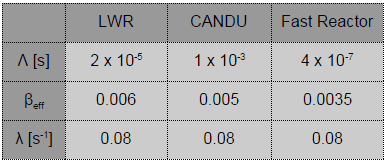

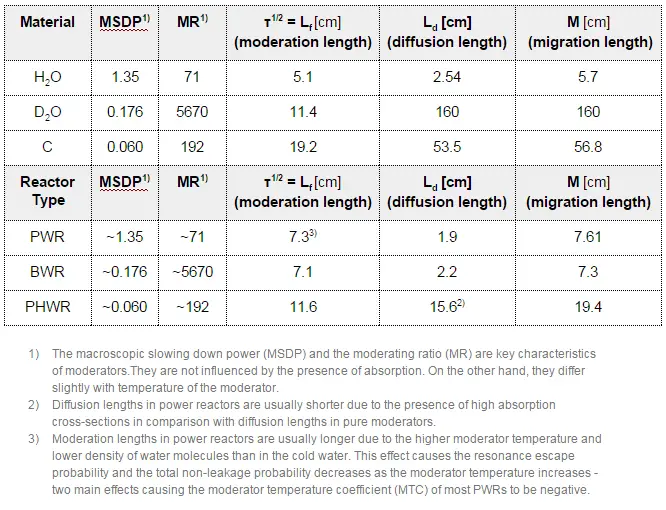

- In reactor design, the prompt neutron lifetime (PNL) belongs to key neutron-physical characteristics of the reactor core.

- Its value depends especially on the type of the moderator and on the energy of the neutrons causing fission.

- In an infinite reactor (without escape), prompt neutron lifetime is the sum of the slowing down time and the diffusion time.

- In LWRs, the PNL increases with the fuel burnup.

- The typical prompt neutron lifetime in thermal reactors is on the order of 10-4 seconds.

- The typical prompt neutron lifetime in fast reactors is on the order of 10-7 seconds.

Key Characteristics of Delayed Neutrons

- The presence of delayed neutrons is perhaps the most important aspect of the fission process from the viewpoint of reactor control.

- Delayed neutrons are emitted by neutron-rich fission fragments that are called delayed neutron precursors.

- These precursors usually undergo beta decay, but a small fraction of them are excited enough to undergo neutron emission.

- The emission of neutrons happens orders of magnitude later compared to the emission of the prompt neutrons.

- About 240 n-emitters are known between 8He and 210Tl, about 75 of them are in the non-fission region.

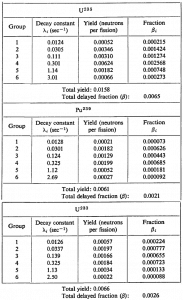

- To simplify reactor kinetic calculations, it is suggested to group together the precursors based on their half-lives.

- Therefore delayed neutrons are traditionally represented by six delayed neutron groups.

- Neutrons can also be produced in (γ, n) reactions (especially in reactors with heavy water moderators), and therefore they are usually referred to as photoneutrons. Photoneutrons are usually treated no differently than delayed neutrons in the kinetic calculations.

- The total yield of delayed neutrons per fission, vd, depends on:

- Isotope that is fissioned.

- Energy of a neutron that induces fission.

- Variation among individual group yields is much greater than variation among group periods.

- In reactor kinetic calculations, it is convenient to use relative units usually referred to as delayed neutron fraction (DNF).

- At the steady-state condition of criticality, with keff = 1, the delayed neutron fraction is equal to the precursor yield fraction β.

- In LWRs, the β decreases with fuel burnup. This is due to isotopic changes in the fuel.

- Delayed neutrons have initial energy between 0.3 and 0.9 MeV with an average energy of 0.4 MeV.

- Depending on the type of the reactor, and their spectrum, the delayed neutrons may be more (in thermal reactors) or less effective than prompt neutrons (in fast reactors). To include this effect into the reactor kinetic calculations, the effective delayed neutron fraction – βeff must be defined.

- The effective delayed neutron fraction is the product of the average delayed neutron fraction and the importance factor βeff = β . I.

- The weighted delayed generation time is given by τ = ∑iτi . βi / β = 13.05 s, therefore the weighted decay constant λ = 1 / τ ≈ 0.08 s-1.

- The mean generation time with delayed neutrons is about ~0.1 s, rather than ~10-5 as in section Prompt Neutron Lifetime, where the delayed neutrons were omitted.

- Their presence completely changes the dynamic time response of a reactor to some reactivity change, making it controllable by control systems such as the control rods.

Point Kinetics Equations

As we have seen in previous chapters, the number of neutrons is multiplied by a factor keff from one neutron generation to the next; therefore, the multiplication environment (nuclear reactor) behaves like the exponential system, which means the power increase is not linear, but it is exponential.

It is obvious the effective multiplication factor in a multiplying system is a measure of the change in the fission neutron population from one neutron generation to the subsequent generation.

It is obvious the effective multiplication factor in a multiplying system is a measure of the change in the fission neutron population from one neutron generation to the subsequent generation.

- keff < 1. Suppose the multiplication factor for a multiplying system is less than 1.0. In that case, the number of neutrons decreases in time (with the mean generation time), and the chain reaction will never be self-sustaining. This condition is known as the subcritical state.

- keff = 1. Suppose the multiplication factor for a multiplying system is equal to 1.0, then there is no change in neutron population in time, and the chain reaction will be self-sustaining. This condition is known as the critical state.

- keff > 1. Suppose the multiplication factor for a multiplying system is greater than 1.0, then the multiplying system produces more neutrons than are needed to be self-sustaining. The number of neutrons is exponentially increasing in time (with the mean generation time). This condition is known as the supercritical state.

But we have not yet discussed the duration of a neutron generation, which means how many times in one second we have to multiply the neutron population by a factor keff. This time determines the speed of the exponential growth. But as was written, there are different types of neutrons: prompt neutrons and delayed neutrons, which completely change the kinetic behavior of the system. Therefore such a discussion will be not trivial.

To study the kinetic behavior of the system, engineers usually use point kinetics equations. The name point kinetics is used because, in this simplified formalism, the neutron flux shape and the neutron density distribution are ignored. The reactor is therefore reduced to a point. In the following section, we will introduce the point kinetics, and we start with point kinetics in its simplest form.

See also: Point Kinetics Equation

Simple Point Kinetics Equation with Delayed Neutrons

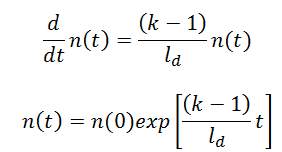

The simplest equation governing the neutron kinetics of the system with delayed neutrons is the simple point kinetics equation with delayed neutrons. This equation states that the time change of the neutron population is equal to the excess of neutron production (by fission) minus neutron loss by absorption in one mean generation time with delayed neutrons (ld).

ld = (1 – β).lp + ∑li . βi => ld = (1 – β).lp + ∑τi . βi

where

- (1 – β) is the fraction of all neutrons emitted as prompt neutrons

- lp is the prompt neutron lifetime

- τi is the mean precursor lifetime, the inverse value of the decay constant τi = 1/λi

- The weighted delayed generation time is given by τ = ∑τi . βi / β = 13.05 s

- Therefore the weighted decay constant λ = 1 / τ ≈ 0.08 s-1

The number, 0.08 s-1, is relatively high and has a dominating effect on reactor time response, although delayed neutrons are a small fraction of all neutrons in the core. This is best illustrated by calculating a weighted mean generation time with delayed neutrons:

ld = (1 – β).lp + ∑τi . βi = (1 – 0.0065). 2 x 10-5 + 0.085 = 0.00001987 + 0.085 ≈ 0.085

In short, the mean generation time with delayed neutrons is about ~0.1 s, rather than ~10-5 as in section Prompt Neutron Lifetime, where the delayed neutrons were omitted.

The role of ld is evident. Longer lifetimes give simply slower responses of multiplying systems. The role of reactivity (keff – 1) is also evident. Higher reactivity gives a larger response of the multiplying system.

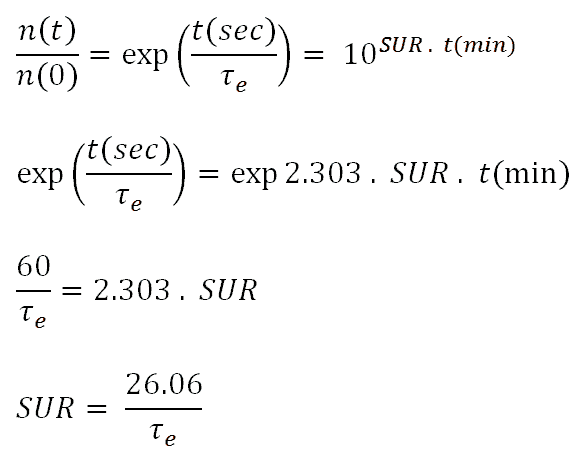

If there are neutrons in the system at t=0, that is, if n(0) > 0, the solution of this equation gives the simplest point kinetics equation with delayed neutrons (similarly to the case without delayed neutrons):

Example:

Let us consider that the mean generation time with delayed neutrons is ~0.085, and k (k∞ – neutron multiplication factor) will be step increased by only 0.01% (i.e., 10pcm or ~1.5 cents); that is, k∞=1.0000 will increase to k∞=1.0001.

It must be noted such reactivity insertion (10pcm) is very small in the case of LWRs (e.g., one step by control rods). The reactivity insertions of the order of one pcm are for LWRs practically unrealizable. In this case, the reactor period will be:

T = ld / (k∞-1) = 0.085 / (1.0001-1) = 850s

This is a very long period. In ~14 minutes, the neutron flux (and power) in the reactor would increase by a factor of e = 2.718. This is completely different dimension of the response on reactivity insertion in comparison with the case without the presence of delayed neutrons, where the reactor period was 1 second.

Inhour Equation

If the reactivity is constant, the model of point kinetics equations contains a set (1 + 6) of linear ordinary differential equations with constant coefficient and can be solved analytically. Solution of six-group point kinetics equations with Laplace transformation leads to the relation between the reactivity and the reactor period. This relation is known as the inhour equation (which comes from an inverse hour, when it was used as a unit of reactivity that corresponded to e-fold neutron density change during one hour) may be derived.

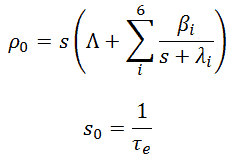

General Form:

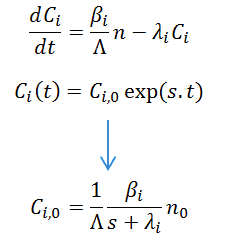

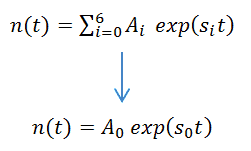

The point kinetics equations may be solved for the case of an initially critical reactor without an external source in which the properties are changed at t = 0 in such a way as to introduce a step reactivity ρ0 which is then constant over time. The system of coupled first-order differential equations can be solved with Laplace transformation or by trying the solution n(t) = A.exp(s.t) (equation for the neutron flux) and Ci(t) = Ci,0.exp(s.t) (equations for the density of precursors).

Substitution of these assumed exponential solutions in the equation for precursors gives the relation between the coefficients of the neutron density and the precursors.

The subsequent substitution in the equation for neutron density yields an equation for s, which after some manipulation can be written as:

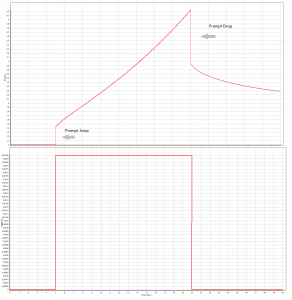

This equation is known as the inhour equation since the constants of s0 – 6 were originally determined in inverse hours. For a given value of the reactivity ρ, the associated values of s0 – 6 are determined with this equation. The following figure shows the relation between ρ and roots s graphically. This figure shows that for a given value of ρ, seven solutions exist for s. The figure indicates that for positive reactivity, only s0 is positive. The remaining terms rapidly die away, yielding an asymptotic solution in the form:

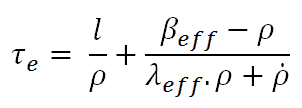

where s0 = 1/τe is the stable reactor period or asymptotic period of the reactor. This root, s0, is positive for ρ > 0 and negative for ρ < 0; therefore, this root describes the reactor response, which is lasting after the transition phenomena have died out. The figure also shows that a negative reactivity leads to a negative period: All of the si are negative, but the root s0 will die away more slowly than the others. Thus the solution n(t) = A0exp(s0t) is valid for positive as well as negative reactivity insertions.

To determine the reactivity required to produce a given period, a plot of ρ vs. τe must be constructed using the delayed neutron data for a particular fissionable isotope or a mix of isotopes, and for a given prompt generation time. To determine the stable reactor period, which results from a given reactivity insertion, it is convenient to use the following form of an inhour equation.

See also: Inhour Equation

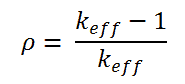

Reactivity

In the preceding chapters, the classification of states of a reactor according to the effective multiplication factor – keff was introduced. The effective multiplication factor – keff is a measure of the change in the fission neutron population from one neutron generation to the subsequent generation. But sometimes, it is convenient to define the change in the keff alone, the change in the state, from the criticality point of view.

For these purposes reactor physics use a term called reactivity rather than keff to describe the change in the state of the reactor core. The reactivity (ρ or ΔK/K) is defined in terms of keff by the following equation:

From this equation, it may be seen that ρ may be positive, zero, or negative. The reactivity describes the deviation of an effective multiplication factor from unity. For critical conditions, the reactivity is equal to zero. The larger the absolute value of reactivity in the reactor core, the further the reactor is from criticality. In fact, the reactivity may be used as a measure of a reactor’s relative departure from criticality.

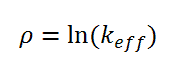

It must be noted the reactivity can also be calculated according to another formula.

This formula is widely used in neutron diffusion or neutron transport codes. The advantage of this reactivity is obvious, it is a measure of a reactor’s relative departure not only from criticality (keff = 1), but it can be related to any sub or supercritical state (ln(k2 / k1)). Another important feature arises from the mathematical properties of the logarithm. The logarithm of the division of k2 and k1 is the difference of the logarithm of k2 and the logarithm of k1. ln(k2 / k1) = ln(k2) – ln(k1). This feature is important in the case of addition and subtraction of various reactivity changes.

See more: D.E.Cullen, Ch.J.Clouse, R.Procassini, R.C.Little. Static and Dynamic Criticality: Are They Different?. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. UCRL-TR-201506. 11/2003.

See more about reactivity.

Reactivity Coefficients – Reactivity Feedbacks

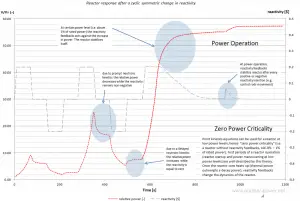

Up to this point, we have discussed the response of the neutron population in a nuclear reactor to an external reactivity input. There was applied an assumption that the level of the neutron population does not affect the properties of the system, especially that the neutron power (power generated by chain reaction) is sufficiently low that the reactor core does not change its temperature (i.e., reactivity feedbacks may be neglected). For this reason, such treatments are frequently referred to as zero-power kinetics.

However, in an operating power reactor, the neutron population is always large enough to generated heat. In fact, it is the main purpose of power reactors to generate a large amount of heat. This causes the system’s temperature to change, and material densities change as well (due to the thermal expansion).

Because macroscopic cross-sections are proportional to densities and temperatures, the neutron flux spectrum also depends on the density of the moderator; these changes, in turn, will produce some changes in reactivity. These changes in reactivity are usually called reactivity feedbacks and are characterized by reactivity coefficients. This is a very important area of reactor design because the reactivity feedbacks influence the stability of the reactor. For example, reactor design must assure that under all operating conditions, the temperature feedback will be negative.

Example: Change in the moderator temperature.

Negative feedback as the moderator temperature effect influences the neutron population in the following way. If the temperature of the moderator is increased, negative reactivity is added to the core. This negative reactivity causes reactor power to decrease. As the thermal power decreases, the power coefficient acts against this decrease, and the reactor returns to the critical condition. The reactor power stabilizes itself. In terms of multiplication factor, this effect is caused by significant changes in the resonance escape probability and in the total neutron leakage (or in the thermal utilization factor when the chemical shim is used).

Reactivity Coefficients

To describe the influence of all these processes on reactivity, one defines the reactivity coefficient α. A reactivity coefficient is defined as the change of reactivity per unit change in some operating parameter of the reactor. For example:

α = dρ⁄dT

The amount of reactivity, which is inserted to a reactor core by a specific change in an operating parameter, is usually known as the reactivity effect and is defined as:

dρ = α . dT

The reactivity coefficients that are important in power reactors (PWRs) are:

- Moderator Temperature Coefficient – MTC

- Fuel Temperature Coefficient or Doppler Coefficient

- Pressure Coefficient

- Void Coefficient

As can be seen, there are not only temperature coefficients that are defined in reactor dynamics. In addition to these coefficients, there are two other coefficients:

The total power coefficient is the combination of various effects and is commonly used when reactors are at power conditions. It is due to the fact, at power conditions it is difficult to separate the moderator effect from the fuel effect and the void effect as well. All these coefficients will be described in following separate sections. The reactivity coefficients are of importance in safety of each nuclear power plant which is declared in the Safety Analysis Report (SAR).

Feedback Delay – Time Constants

In physics and engineering, the time constant is the parameter characterizing the response to a step input of a first-order, linear time-invariant system. The time constant is usually denoted by the Greek letter τ (tau). It is obvious that thermal time constants, which characterize the time required to warm an object by another object, are of importance for reactor stability. In general, the heat transfer from the body to the ambient at a given time is proportional to the temperature difference between the body and the ambient. The time constants that determine the time delays for reactivity feedbacks depend on the specific reactor design. For LWRs, the following time constants are usual:

- The time constant for heating fuel is almost zero; therefore, the fuel temperature coefficient is effective almost instantaneously.

- The time constant for heat transfer out of a fuel pin varies from a few tenths to a few tens of seconds. The time for heat to be transferred to the moderator is usually measured in seconds (~5s). The presence of the surface film increases the time constant for the fuel element.

- The time constant for equalization of temperatures within the primary loop depends strongly on the length of primary piping and the flow velocity. It is usually measured in seconds (<10s)

Knowledge of delays of reactivity feedbacks is very important in the study of reactor transients. A large reactivity insertion will cause a reactor to go on such a short period that the power changes significantly over a short time span compared to the number of seconds needed to transfer heat from fuel to coolant. Especially in the case of all reactivity-initiated accidents (RIA), over short time spans, the amount of heat transferred to the coolant is not enough to increase its temperature appreciably. Therefore, the fuel temperature coefficient will be the first and the most important feedback that will compensate for the inserted positive reactivity. The time for heat to be transferred to the moderator is usually measured in seconds, while the fuel temperature coefficient is effective almost instantaneously. Therefore this coefficient is also called the prompt temperature coefficient because it causes an immediate response to changes in fuel temperature.

Point Dynamics Equations

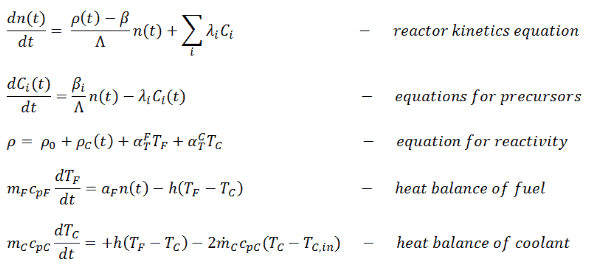

A simple point dynamics model is based on point kinetics equations, but here we should take into account the influence of the fuel and the moderator temperature on the reactivity. We assume there are no other feedbacks, and therefore this simple model can be applied only on PWRs. For example, the void coefficient is neglected here. In systems with boiling conditions, such as boiling water reactors (BWR), the void coefficient is of prime importance during reactor operation.

Thus, the simplest point dynamics model of PWR should take into consideration the time variations of the fuel and coolant temperature. The point dynamics model consist of the following equations:

- The first equation is the equation for neutrons. The first term on the right-hand side is the production of prompt neutrons in the present generation, minus the total number of neutrons in the preceding generation. The second term is the production of delayed neutrons in the present generation.

- The second equation is the equation for precursors. There is a balance between the production of the precursors of i-th group and their decay after the decay constant λi. As can be seen, the decay rate of precursors is the radioactivity rate (λiCi), and the rate of production is proportional to the number of neutrons times βi, which is defined as the fraction of the neutrons which appear as delayed neutrons in the ith group.

- The third equation expresses the dependence of the reactivity on various parameters. But in this case, there is a dependence on the coolant and the fuel temperature only. ρ0 is the initial reactivity, whereas ρC (t) is time-dependent reactivity inserted by a reactor control system (e.g., by control rods or by boron dilution). This is the feedback equation.

- The equations of the heat balance for fuel and coolant are interconnected via h(TF – TC), which represents the heat transfer from the fuel into the coolant. In these equations, mF and mC are the mass of fuel and coolant in the core, respectively, cpF and cpC are specific heat capacities of fuel and coolant, h is the heat transfer coefficient between fuel and coolant, mC dotted is the coolant mass flow rate [kg/s] and TC and TC,in are the average and inlet coolant temperature, respectively.

To solve the point dynamics equations, it is necessary to specify the initial conditions, like in the case of point kinetics.

See also: Reactor Stability

What means under and over-moderated reactor?

Test your Knowledge – Reactor Dynamics

With our simple quizzes, you can test your knowledge.

It is intuitive: start quiz and answer questions.