The reduction of reactivity is a combinative effect of:

- the net reduction of fissile nuclides,

- the production of neutron-absorbing nuclides (non-fissile actinides and fission products)

Spent nuclear fuel is characterized by fuel burnup, a measure of how much energy is extracted from nuclear fuel, and a measure of fuel depletion. Due to fuel depletion and fission fragments buildup, spent nuclear fuel is no longer useful in sustaining a nuclear reaction in an ordinary thermal reactor and must be replaced by fresh fuel. It may have considerably different isotopic constituents depending on its point along the nuclear fuel cycle.

It must be noted that irradiated fuel is due to the presence of a high amount of radioactive fission fragments and transuranic elements that are very hot and very radioactive. Reactor operators must manage the heat and radioactivity that remains in the “spent fuel” after it’s taken out of the reactor. In nuclear power plants, spent nuclear fuel is stored underwater in the spent fuel pool, and plant personnel moves the spent fuel underwater from the reactor to the pool. Over time, as the spent fuel is stored in the pool, it becomes cooler as the radioactivity decays away. After several years (> 5 years), decay heat decreases under specified limits so that spent fuel may be reprocessed or interim storage.

At first glance, it isn’t easy to recognize fresh fuel from used fuel. From a mechanical point of view, the used fuel (irradiated) is identical to the fresh fuel. In most PWRs, used fuel assemblies stand between four and five meters high, are about 20 cm across, and weigh about half a tonne. A PWR fuel assembly comprises a bottom nozzle into which rods are fixed through the lattice, and it is ended by a top nozzle to finish the whole assembly. There are spacing grids between these nozzles. These grids ensure an exact guiding of the fuel rods. The bottom and top nozzles are heavily constructed as they provide much mechanical support for the fuel assembly structure. Western PWRs use a square lattice arrangement, and assemblies are characterized by the number of rods they contain, typically 17×17 in current designs. In contrast to the fresh fuel, which is simply shiny, the oxide layer forming on the surface of used fuel assemblies during the four-year fuel cycle makes them dark. Moreover, Cherenkov radiation is typical only for spent nuclear fuel. The glow is also visible after the chain reaction stops (in the reactor). The Cherenkov radiation can characterize the remaining radioactivity of spent nuclear fuel. Therefore it can be used for measuring fuel burnup.

Spent Nuclear Fuel – Burnup

As was written, spent nuclear fuel is characterized by fuel burnup, which defines energy release and the isotopic composition of irradiated fuel. Reactor engineers distinguish between:

- Core Burnup. Averaged burnup over the entire core (i.e., overall fuel assemblies). For example – BUcore = 25 000 MWd/tHM. This value does not characterize spent fuel.

- Fuel Assembly Burnup. Averaged burnup over single assembly (i.e., overall fuel pins of a single fuel assembly). For example – BUFA = 50 000 MWd/tHM. This value is typical for spent fuel.

- Pin Burnup. Averaged burnup over a single fuel pin or fuel rod (overall fuel pellets of a single fuel pin). For example – BUpin = 55 000 MWd/tHM. Fuel rods never have identical burnup. They differ slightly, and limitations are usually set for fuel rod burnup due to design considerations (e.g., internal pressure).

- Local or Fine Mesh Burnup. Burnup significantly varies also within a single fuel pellet. For example, the local burnup at the rim of the UO2 pellet can be 2–3 times higher than the average pellet burnup. This local anomaly causes the formation of a structure known as a High Burnup Structure.

Spent Nuclear Fuel – Composition

As a reactor is operated at significant power, fuel atoms are constantly consumed, resulting in the slow depletion of the fuel. It must be noted there are also research reactors, which have very low power, and the fuel in these reactors does not change its isotopic composition.

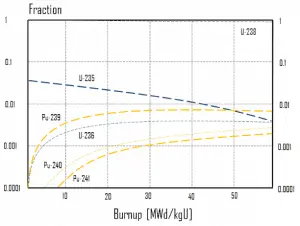

Research reactors with significant thermal power and all power reactors are subjected to significant isotopic changes. The study of these isotopic changes is known as long-term kinetics, which describes phenomena that occur over months or even years. Most common reactor fuels are composed of either natural or partially enriched uranium. Typically, PWRs use an enriched uranium fuel (~4% of U-235) as a fresh fuel. Exposure to neutron flux gradually depletes the uranium-235, decreasing core reactivity (compensated by control rods, chemical shim, or burnable absorbers). The initial fuel load of a new reactor core (so-called first core) is entirely fresh fuel, fuel with no plutonium or fission products. The contribution of uranium-238 directly to fission is quite small in most thermal reactors. On the other hand, uranium-238 plays a very important role since plutonium-239 is formed in a nuclear reactor from fertile isotope 238U.

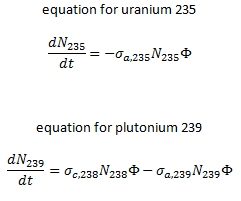

Evolution Equations

The exact evolution of isotopic changes is usually modeled mathematically by a set of differential equations known as evolution equations. These equations describe the rate of burnup of U-235, the rate of buildup of Pu-239, the production of Pu-240 and Pu-241, the buildup of neutron-absorbing fission products, and the overall rate of reactivity change in the reactor due to the changing composition of the fuel. The evolution equation can be constructed for each isotope. For example:

Special reference: W. M. Stacey, Nuclear Reactor Physics, John Wiley & Sons, 2001, ISBN: 0- 471-39127-1.

Special reference: Paul Reuss, Neutron Physics, EDP Sciences, 2008, ISBN: 2759800415.

In summary, the following points are the main isotopic changes for fuel at fuel burnup of 40 GWd/tU:

- Approximately 3 – 4% of the heavy nuclei are fissioned.

- About two-thirds of these fissions come directly from uranium 235, and the other third from plutonium, which is produced from uranium 238. The contribution significantly increases as the fuel burnup increases.

- The removed fuel (spent nuclear fuel) still contains about 96% of reusable material. It must be removed due to decreasing kinf of an assembly, or in other words, it must be removed due to accumulation of fission products with significant absorption cross-section.

- Discharged fuel contains about 0.8% plutonium and about 1% uranium 235. It must be noted that there is a significant content (about 0.5%) of uranium 236, which is neither a fissile isotope nor a fertile isotope.

Fission Products in SNF

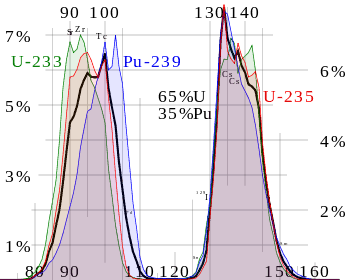

Nuclear fission products are the fragments left after a nucleus fissions. Typically, when the uranium 235 nucleus undergoes fission, the nucleus splits into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, and releases energy in the form of heat (kinetic energy of these fission fragments) and gamma rays. The average fragment mass is about 118, but very few fragments near that average are found. It is much more probable to break up into unequal fragments, and the most probable fragment masses are around mass 95 (Krypton) and 137 (Barium). The fission products include every element from zinc through to the lanthanides; much of the fission yield is concentrated in two peaks, one in the second transition row (Zr, Mo, Tc, Ru, Rh, Pd, Ag) and the other later in the periodic table (I, Xe, Cs, Ba, La, Ce, Nd). Most of these fission fragments are highly unstable (radioactive) and undergo further radioactive decays to stabilize themselves. Many of the fission products are only short-lived radioisotopes. But many are medium to long-lived radioisotopes such as 90Sr, 137Cs, 99Tc, and 129I.

Nuclear fission products are the fragments left after a nucleus fissions. Typically, when the uranium 235 nucleus undergoes fission, the nucleus splits into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, and releases energy in the form of heat (kinetic energy of these fission fragments) and gamma rays. The average fragment mass is about 118, but very few fragments near that average are found. It is much more probable to break up into unequal fragments, and the most probable fragment masses are around mass 95 (Krypton) and 137 (Barium). The fission products include every element from zinc through to the lanthanides; much of the fission yield is concentrated in two peaks, one in the second transition row (Zr, Mo, Tc, Ru, Rh, Pd, Ag) and the other later in the periodic table (I, Xe, Cs, Ba, La, Ce, Nd). Most of these fission fragments are highly unstable (radioactive) and undergo further radioactive decays to stabilize themselves. Many of the fission products are only short-lived radioisotopes. But many are medium to long-lived radioisotopes such as 90Sr, 137Cs, 99Tc, and 129I.

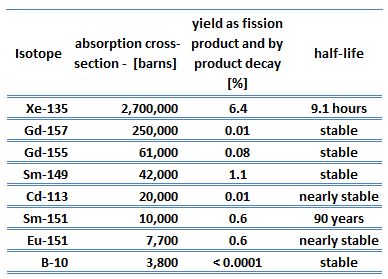

An isotope that is long-lived or even stable is known as reactor slag. The accumulation of these parasitic absorbers is known as reactor slagging and determines the lifetime of nuclear fuel in a reactor since their buildup causes (together with a decrease in fissile material) a continuous decrease in core reactivity.

An isotope that is long-lived or even stable is known as reactor slag. The accumulation of these parasitic absorbers is known as reactor slagging and determines the lifetime of nuclear fuel in a reactor since their buildup causes (together with a decrease in fissile material) a continuous decrease in core reactivity.

Samarium 149 belongs to this group of isotopes, but its importance is so high that it is usually discussed separately. As can be seen from the table, there are numerous other fission products that, as a result of their concentration and thermal neutron absorption cross-section, have a poisoning effect on reactor operation. Other fission products with relatively high absorption cross sections include 83Kr, 95Mo, 143Nd, and 147Pm. Individually, they are of little consequence but taken together, they have a significant effect. These are often characterized as lumped fission product poisons.

Spent Fuel Decay Heat

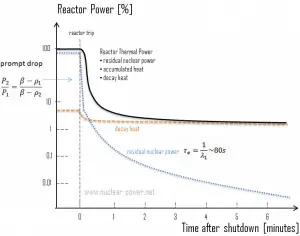

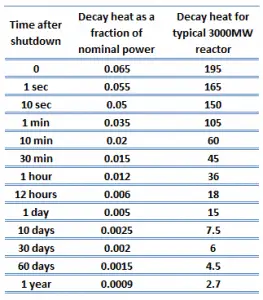

Fission essentially ceases when a reactor is shut down, but decay energy is still produced. The energy produced after shutdown is referred to as decay heat. The amount of decay heat production after shutdown is directly influenced by the reactor’s power history (fission products accumulation) before shutdown and by the level of fuel burnup (actinides accumulation – especially in the case of spent fuel handling). A reactor operated at full power for 10 days before shutdown has much higher decay heat generation than a reactor operated at low power for the same period. On the other hand, when the reactor changes its power from 50% to 100% of full power, the decay heat to neutron power ratio drops to roughly half its previous level. It builds up slowly as the fission product inventory adjusts to the new power.

Fission essentially ceases when a reactor is shut down, but decay energy is still produced. The energy produced after shutdown is referred to as decay heat. The amount of decay heat production after shutdown is directly influenced by the reactor’s power history (fission products accumulation) before shutdown and by the level of fuel burnup (actinides accumulation – especially in the case of spent fuel handling). A reactor operated at full power for 10 days before shutdown has much higher decay heat generation than a reactor operated at low power for the same period. On the other hand, when the reactor changes its power from 50% to 100% of full power, the decay heat to neutron power ratio drops to roughly half its previous level. It builds up slowly as the fission product inventory adjusts to the new power.

The decay heat produced after a reactor shutdown from full power is initially equivalent to about 6 to 7% of the rated thermal power. Since radioactive decay is a random process at the level of single atoms, it is governed by the radioactive decay law. Note that irradiated nuclear fuel contains many different isotopes that contribute to decay heat, all subject to the radioactive decay law. Therefore a model describing decay heat must consider decay heat to be a sum of exponential functions with different decay constants and initial contribution to the heat rate. Fission fragments with a short half-life are much more radioactive (at the time of production) and contribute significantly to decay heat but will lose their share rapidly. On the other hand, fission fragments and transuranic elements with a long half-life are less radioactive (at the time of production) and produce less decay heat but will lose their share more slowly. This decay heat generation rate diminishes to about 1% approximately one hour after shutdown. As was written, the decay comes from the beta and gamma decay of fission products and transuranic elements (+ alpha decay).

The decay heat produced after a reactor shutdown from full power is initially equivalent to about 6 to 7% of the rated thermal power. Since radioactive decay is a random process at the level of single atoms, it is governed by the radioactive decay law. Note that irradiated nuclear fuel contains many different isotopes that contribute to decay heat, all subject to the radioactive decay law. Therefore a model describing decay heat must consider decay heat to be a sum of exponential functions with different decay constants and initial contribution to the heat rate. Fission fragments with a short half-life are much more radioactive (at the time of production) and contribute significantly to decay heat but will lose their share rapidly. On the other hand, fission fragments and transuranic elements with a long half-life are less radioactive (at the time of production) and produce less decay heat but will lose their share more slowly. This decay heat generation rate diminishes to about 1% approximately one hour after shutdown. As was written, the decay comes from the beta and gamma decay of fission products and transuranic elements (+ alpha decay).

See also: Decay Heat

Typical Long-lived Radionuclides – Spent Fuel

Actinides

- 239Pu. 239Pu belongs to the group of fissile isotopes. 239Pu decays via alpha decay to 235U with a half-life of 24100 years. This isotope is the principal fissile isotope in use.

- 240Pu. 240Pu belongs to the group of fertile isotopes. 240Pu decays via alpha decay to 236U with a half-life of 6560 years. 240Pu has a very high rate of spontaneous fission and a high radiative capture cross-section for thermal and resonance neutrons.

- 236U. 236U is neither a fissile isotope nor a fertile isotope. 236U is fissionable only by fast neutrons. Isotope 236U is formed in a nuclear reactor from fissile isotope 235U. 236U decays via alpha decay to 232Th with a half-life of ~2.3×107 years. 236U occasionally decays by spontaneous fission with a very low probability of 0.00000009%. Its specific activity is ~6.5×10-5 Ci/g.

Fission Products

- 135Cs. 135Cs is a fission product (yield: 6.911%) with a half-life of ~2.3×106 years.

- 99Tc. 99Tc is a fission product (yield: 6.139%) with a half-life of ~0.211×106 years.

- 93Zr. 93Zr is a fission product (yield: 5.458%) with a half-life of ~1.53×106 years.

- 129I. 129I is a fission product (yield: 0.841%) with a half-life of ~15.7×106 years.

Typical Medium-lived Radionuclides – Spent Fuel

Actinides

- 241Pu. 241Pu belongs to the group of fissile isotopes. 241Pu decays via negative beta decay to 241Am with a half-life of 14.3 years. This fissile isotope decays to a non-fissile isotope with a high radiative capture cross-section for thermal neutrons. An impact on the reactivity of nuclear fuel is obvious.

- 232U. 232U belongs to the group of fertile isotopes. 232U is a side product in the thorium fuel cycle, and this isotope is a decay product of 236Pu in the uranium fuel. 232U decays via alpha decay to 228Th with a half-life of 68.9 years. 232U very rarely decays by spontaneous fission. Its specific activity is very high, ~22 Ci/g, and its decay chain produces very penetrating gamma rays.

Fission Products

- 137Cs. 137Cs is a fission product (yield: 6.337%) with a half-life of ~ 30.23 years.

- 90Sr. 90Sr is a fission product (yield: 4.505%) with a half-life of ~ 28.9 years.

- 151Sm. 151Sm is a fission product (yield: 0.531%) with a half-life of ~ 88.8 years.

- 85Kr. 85Kr is a fission product (yield: 0.218%) with a half-life of ~ 10.76 years.

Reactor Refueling

The key feature of LWRs fuel cycles is that many fuel assemblies in the core have different multiplying properties because they may have different enrichment and burn up. Generally, a common fuel assembly contains energy for approximately 4 years of operation at full power. Once loaded, the fuel stays in the core for 4 years, depending on the design of the operating cycle. During these 4 years, the reactor core has to be refueled. During refueling, every 12 to 18 months, some of the fuel – usually one-third or one-quarter of the core – is removed from the spent fuel pool. At the same time, the remainder is rearranged to a location in the core better suited to its remaining level of enrichment. The refueling machine usually does this. The removed fuel (one-third or one-quarter of the core, i.e., 40 assemblies) has to be replaced by fresh fuel assemblies. Over time, as the spent fuel is stored in the pool, it becomes cooler as the radioactivity decays away. After several years (> 5 years), decay heat decreases under specified limits so that spent fuel may be reprocessed or interim storage.

The refueling operation is divided into six major phases:

- preparation,

- reactor disassembly,

- fuel handling,

- reactor reassembly,

- preoperational checks, tests,

- reactor startup.

Refueling and Samarium Removal

An important difference between Xe-135 and Sm-149 is that samarium 149 is a stable isotope and remains in the core after shutdown. There are only two ways of samarium removal, and one of these processes is the samarium burning up when the reactor is in power operation. The samarium burnup rate depends upon the neutron flux and the samarium 149 concentration (i.e., the reaction rate).

The second process is associated with refueling. During refueling, one-third or one-quarter of the core is usually removed from the spent fuel pool and replaced by fresh fuel assemblies. At the same time, the remainder is rearranged to a location in the core better suited to its remaining level of enrichment. Therefore, refueling naturally decreases the overall samarium content in the core.

Annual Production of SNF

Consumption of a 3000MWth (~1000MWe) reactor (12-month fuel cycle)

It is an illustrative example, and the following data do not correspond to any reactor design.

- A typical reactor may contain about 165 tonnes of fuel (including structural material)

- A typical reactor may contain about 100 tonnes of enriched uranium (i.e., about 113 tonnes of uranium dioxide).

- This fuel is loaded within, for example, 157 fuel assemblies composed of over 45,000 fuel rods.

- A common fuel assembly contains energy for approximately 4 years of operation at full power.

- Therefore about one-quarter of the core is yearly removed from the spent fuel pool (i.e., about 40 fuel assemblies). At the same time, the remainder is rearranged to a location in the core better suited to its remaining level of enrichment (see Power Distribution).

- The removed fuel (spent nuclear fuel) still contains about 96% of reusable material (must be removed due to decreasing kinf of an assembly).

- The annual spent nuclear fuel production of this reactor is about 25 tonnes. If the fuel were reprocessed and vitrified, the waste volume would be only about three cubic meters per year, but the decay heat would be almost the same.