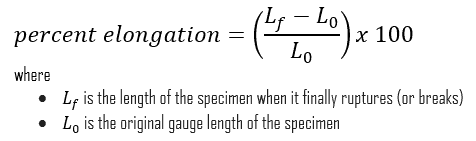

Some materials break very sharply, without plastic deformation, in a brittle failure. Others, which are more ductile, including most metals, experience some plastic deformation and possibly necking before fracture. In materials science, ductility is the ability of a material to undergo large plastic deformations before failure. It is one of the very important characteristics that engineers consider during design. Ductility may be expressed as percent elongation or percent area reduction from a tensile test. Ductility is important in allowing a structure to survive extreme loads, such as those due to large pressure changes, earthquakes, and hurricanes, without experiencing a sudden failure or collapse. It is defined as:

Some materials break very sharply, without plastic deformation, in a brittle failure. Others, which are more ductile, including most metals, experience some plastic deformation and possibly necking before fracture. In materials science, ductility is the ability of a material to undergo large plastic deformations before failure. It is one of the very important characteristics that engineers consider during design. Ductility may be expressed as percent elongation or percent area reduction from a tensile test. Ductility is important in allowing a structure to survive extreme loads, such as those due to large pressure changes, earthquakes, and hurricanes, without experiencing a sudden failure or collapse. It is defined as:

In the case of the tension test, ductility is measured by a percent reduction in area. It measures the amount of necking (or change in cross-sectional area) that occurs before the ultimate failure as follows:

It is possible to distinguish some common characteristics among the stress-strain curves of various groups of materials. On this basis, it is possible to divide materials into two broad categories; namely:

- Ductile Materials. Ductility is the ability of a material to be elongated in tension. Ductile material will deform (elongate) more than brittle material. Ductile materials show large deformation before fracture. In ductile fracture, extensive plastic deformation (necking) takes place before fracture. Ductile fracture (shear fracture) is better than brittle fracture because there is slow propagation and an absorption of a large amount of energy before fracture. Ductility is desirable in the high temperature and high-pressure applications in reactor plants because of the added stresses on the metals. High ductility in these applications helps prevent brittle fracture.

- Brittle Materials. When stress subjects, brittle materials break with little elastic deformation and without significant plastic deformation. Brittle materials absorb relatively little energy before fracture, even high-strength materials. In brittle fracture (transgranular cleavage), no apparent plastic deformation occurs before fracture, and cracks propagate rapidly.

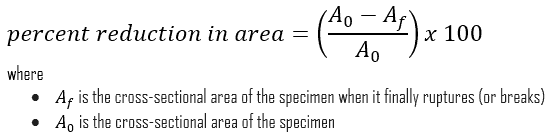

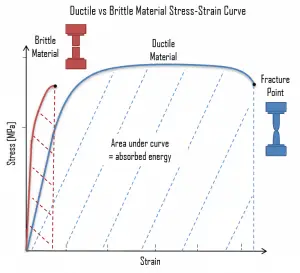

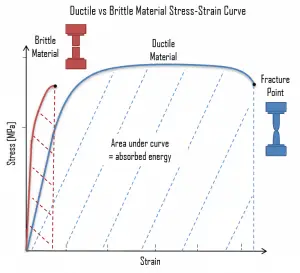

The distinction between brittleness and ductility isn’t readily apparent, especially because both ductility and brittle behavior depend not only on the material in question but also on the nature and type of stress, the rate of loading (fatigue wear), and the temperature (ductile-brittle transition). The following figure shows a typical stress-strain curve of ductile and brittle materials. Ductile material is a material with a small strength, and the plastic region is great, and the material will bear more strain (deformation) before fracture. A brittle material is a material where the plastic region is small, and the strength of the material is high. The tensile test supplies three descriptive facts about a material. These are the stress at which observable plastic deformation or “yielding” begins; the ultimate tensile strength or maximum intensity of load that can be carried in tension; and the percent elongation or strain (the amount the material will stretch) and the accompanying percent reduction of the cross-sectional area caused by stretching. The rupture or fracture point can also be determined.

Ductility and Toughness

Ductility is more commonly defined as the ability of a material to deform easily upon the application of a tensile force or as the ability of a material to withstand plastic deformation without rupture. Ductility may also be thought of in terms of bendability and crushability. Usually, if two materials have the same strength and hardness, the one with the higher ductility is more desirable. The ductility of many metals can change if conditions are altered. An increase in temperature will increase ductility. A decrease in temperature will cause a decrease in ductility and a change from ductile to brittle behavior. Ductile fracture (shear fracture) is better than brittle fracture because there is slow propagation and an absorption of a large amount of energy before fracture. Ductility is desirable in the high temperature and high-pressure applications in reactor plants because of the added stresses on the metals. High ductility in these applications helps prevent brittle fracture. Ductility also contributes to another material property called toughness. Toughness combines strength and ductility in a single measurable property and requires a balance of strength and ductility.

Toughness is the ability of a material to absorb energy and plastically deform without fracturing. One definition of toughness (or, more specifically, fracture toughness) is that it is a property that is indicative of a material’s resistance to fracture when a crack (or other stress-concentrating defects) is present. Toughness is typically measured by the Charpy test or the Izod test. The impact test measures toughness under conditions of sudden loading and the presence of flaws such as notches or cracks, which will concentrate stress at weak points. Toughness can also be defined for regions of a stress-strain diagram. Toughness is related to the area under the stress-strain curve. The stress-strain curve measures toughness under a gradually increasing load. The material must be both strong and ductile to be tough. The following figure shows a typical stress-strain curve of ductile and brittle materials. For example, brittle materials (like ceramics) that are strong but with limited ductility are not tough; conversely, very ductile materials with low strengths are also not tough. A material should withstand both high stresses and high strains to be tough.

Toughness is the ability of a material to absorb energy and plastically deform without fracturing. One definition of toughness (or, more specifically, fracture toughness) is that it is a property that is indicative of a material’s resistance to fracture when a crack (or other stress-concentrating defects) is present. Toughness is typically measured by the Charpy test or the Izod test. The impact test measures toughness under conditions of sudden loading and the presence of flaws such as notches or cracks, which will concentrate stress at weak points. Toughness can also be defined for regions of a stress-strain diagram. Toughness is related to the area under the stress-strain curve. The stress-strain curve measures toughness under a gradually increasing load. The material must be both strong and ductile to be tough. The following figure shows a typical stress-strain curve of ductile and brittle materials. For example, brittle materials (like ceramics) that are strong but with limited ductility are not tough; conversely, very ductile materials with low strengths are also not tough. A material should withstand both high stresses and high strains to be tough.

Ductile–brittle Transition Temperature

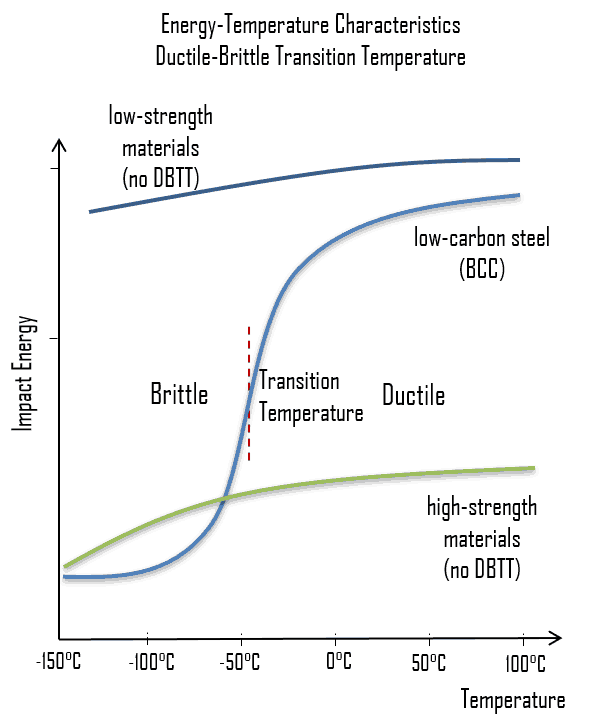

As was written, the distinction between brittleness and ductility isn’t readily apparent, especially because both ductility and brittle behavior are dependent not only on the material in question but also on the temperature (ductile-brittle transition) of the material. The effect of temperature on the nature of the fracture is of considerable importance, and many steels exhibit ductile fracture at elevated temperatures and brittle fracture at low temperatures. The temperature above which material is ductile and below which it is brittle is known as the ductile-brittle transition temperature (DBTT), nil ductility temperature (NDT), or nil ductility transition temperature. This temperature is not precise but varies according to prior mechanical and heat treatment and the nature and amounts of impurity elements. It can be determined by some form of drop-weight test (for example, the Charpy or Izod tests).

The ductile-brittle transition temperature (DBTT) is the temperature at which the fracture energy passes below a predetermined value (e.g., 40 J for a standard Charpy impact test). Ductility is an essential requirement for the steel construction of reactor components, such as the reactor vessel. Therefore, the DBTT is of significance in the operation of these vessels. In this case, the grain’s size determines the metal’s properties. For example, smaller grain size increases tensile strength, tends to increase ductility, and decreases DBTT. Grain size is controlled by heat treatment in the specifications and manufacturing of reactor vessels. The DBTT can also be lowered by small additions of selected alloying elements such as nickel and manganese to low-carbon steels.

The ductile-brittle transition temperature (DBTT) is the temperature at which the fracture energy passes below a predetermined value (e.g., 40 J for a standard Charpy impact test). Ductility is an essential requirement for the steel construction of reactor components, such as the reactor vessel. Therefore, the DBTT is of significance in the operation of these vessels. In this case, the grain’s size determines the metal’s properties. For example, smaller grain size increases tensile strength, tends to increase ductility, and decreases DBTT. Grain size is controlled by heat treatment in the specifications and manufacturing of reactor vessels. The DBTT can also be lowered by small additions of selected alloying elements such as nickel and manganese to low-carbon steels.

Typically, the low alloy reactor pressure vessel steels are ferritic steels that exhibit the classic ductile-to-brittle transition behavior with decreasing temperature. This transitional temperature is of the highest importance during plant heat-up.

Failure modes:

- Low toughness region: Main failure mode is the brittle fracture (transgranular cleavage). In brittle fracture, no apparent plastic deformation takes place before fracture. Cracks propagate rapidly.

- High toughness region: Main failure mode is the ductile fracture (shear fracture). In ductile fracture, extensive plastic deformation (necking) takes place before fracture. Ductile fracture is better than brittle fracture because there is slow propagation and an absorption of a large amount of energy before fracture.

In some materials, the transition is sharper than in others and typically requires a temperature-sensitive deformation mechanism. For example, in materials with a body-centered cubic (bcc) lattice, the DBTT is readily apparent, as the motion of screw dislocations is very temperature sensitive because the rearrangement of the dislocation core before slip requires thermal activation. This can be problematic for steels with a high ferrite content. This famously resulted in serious hull cracking in Liberty ships in colder waters during World War II, causing many sinkings. The vessels were constructed of a steel alloy with adequate toughness according to room-temperature tensile tests. The brittle fractures occurred at relatively low ambient temperatures, at about 4°C (40°F), in the vicinity of the transition temperature of the alloy. It must be noted that low-strength FCC metals (e.g., copper alloys) and most HCP metals do not experience a ductile-to-brittle transition and retain tough also for lower temperatures. On the other hand, many high-strength metals (e.g., very high-strength steels) also do not experience a ductile-to-brittle transition, but, in this case, they remain very brittle.

DBTT can also be influenced by external factors such as neutron radiation, which leads to an increase in internal lattice defects, a corresponding decrease in ductility, and an increase in DBTT.

Irradiation Embrittlement

During the operation of a nuclear power plant, the material of the reactor pressure vessel and the material of other reactor internals are exposed to neutron radiation (especially to fast neutrons >0.5MeV), which results in localized embrittlement of the steel and welds in the area of the reactor core. This phenomenon, known as irradiation embrittlement, results in a steady increase in DBTT. It is not likely that the DBTT will approach the normal operating temperature of the steel. However, there is a possibility that when the reactor is being shut down or during an abnormal cooldown, the temperature may fall below the DBTT value. At the same time, the internal pressure is still high. Therefore nuclear regulators require that a reactor vessel material surveillance program be conducted in water-cooled power reactors.

See also: Neutron Reflector

Irradiation embrittlement can lead to loss of fracture toughness. Typically, the low alloy reactor pressure vessel steels are ferritic steels that exhibit the classic ductile-to-brittle transition behavior with decreasing temperature. This transitional temperature is of the highest importance during plant heat-up.

Failure modes:

- Low toughness region: Main failure mode is the brittle fracture (transgranular cleavage). In brittle fracture, no apparent plastic deformation takes place before fracture. Cracks propagate rapidly.

- High toughness region: Main failure mode is the ductile fracture (shear fracture). In ductile fracture, extensive plastic deformation (necking) takes place before fracture. Ductile fracture is better than brittle fracture because there is slow propagation and an absorption of a large amount of energy before fracture.

Neutron irradiation tends to increase the temperature (ductile-to-brittle transition temperature) at which this transition occurs and decrease the ductile toughness.