Stone wool, also known as rock wool, is based on natural minerals present in large quantities throughout the earth, e.g., volcanic rock, typically basalt or dolomite. Next to raw materials, recycled rock wool can be added to the process, and slag residues from the metal industry. It combines mechanical resistance with good thermal performance, fire safety, and high-temperature suitability. Glass‐ and stone wool are produced from mineral fibers and are often referred to as ‘mineral wools’. Mineral wool is a general name for fiber materials formed by spinning or drawing molten minerals. Stone wool is a furnace product of molten rock at a temperature of about 1600 °C, through which a stream of air or steam is blown. More advanced production techniques are based on spinning molten rock in high-speed spinning heads, somewhat like the process used to produce cotton candy.

Stone wool, also known as rock wool, is based on natural minerals present in large quantities throughout the earth, e.g., volcanic rock, typically basalt or dolomite. Next to raw materials, recycled rock wool can be added to the process, and slag residues from the metal industry. It combines mechanical resistance with good thermal performance, fire safety, and high-temperature suitability. Glass‐ and stone wool are produced from mineral fibers and are often referred to as ‘mineral wools’. Mineral wool is a general name for fiber materials formed by spinning or drawing molten minerals. Stone wool is a furnace product of molten rock at a temperature of about 1600 °C, through which a stream of air or steam is blown. More advanced production techniques are based on spinning molten rock in high-speed spinning heads, somewhat like the process used to produce cotton candy.

Applications of stone wool include structural insulation, pipe insulation, filtration, soundproofing, and hydroponic growth medium. Stone wool is a versatile material that can be used to insulate walls, roofs, and floors. During the installation of the stone wool, it should be kept dry at all times since an increase in the moisture content causes a significant increase in thermal conductivity.

Thermal Conductivity of Stone Wool

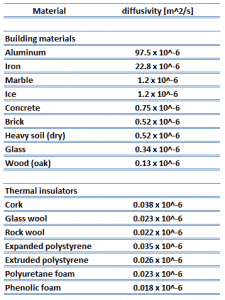

Thermal conductivity is defined as the amount of heat (in watts) transferred through a square area of material of a given thickness (in meters) due to a difference in temperature. The lower the thermal conductivity of the material, the greater the material’s ability to resist heat transfer, and hence the greater the insulation’s effectiveness. Typical thermal conductivity values for mineral wools are between 0.020 and 0.040W/m∙K.

Thermal conductivity is defined as the amount of heat (in watts) transferred through a square area of material of a given thickness (in meters) due to a difference in temperature. The lower the thermal conductivity of the material, the greater the material’s ability to resist heat transfer, and hence the greater the insulation’s effectiveness. Typical thermal conductivity values for mineral wools are between 0.020 and 0.040W/m∙K.

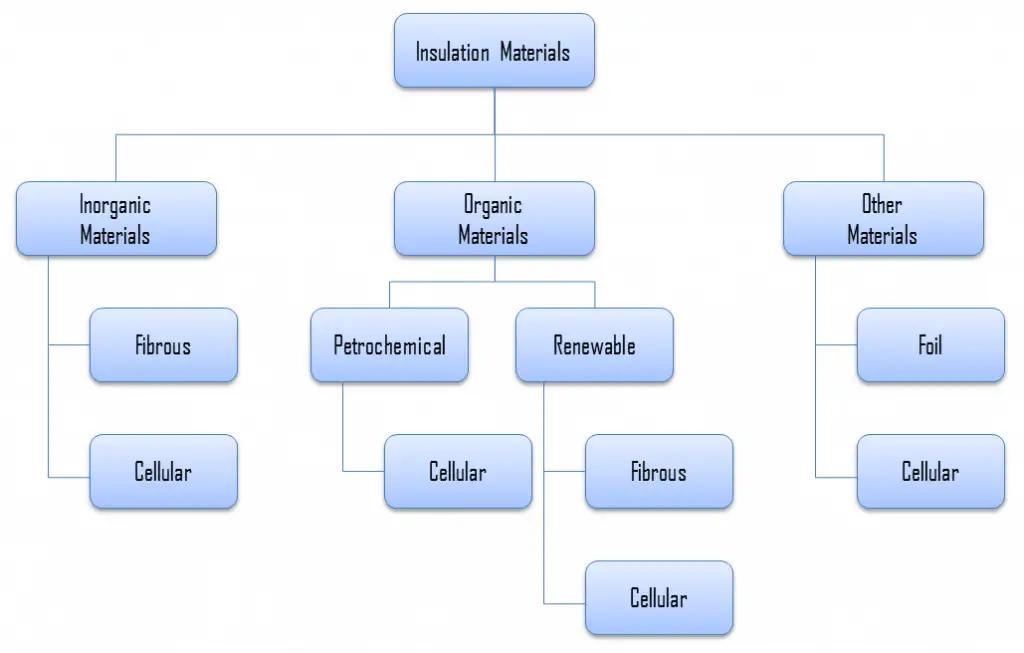

In general, thermal insulation is primarily based on the very low thermal conductivity of gases. Gases possess poor thermal conduction properties compared to liquids and solids and thus make a good insulation material if they can be trapped (e.g., in a foam-like structure). Air and other gases are generally good insulators. But the main benefit is in the absence of convection. Therefore, many insulating materials (e.g., stone wool) function simply by having a large number of gas-filled pockets which prevent large-scale convection.

Alternation of gas pocket and solid material causes that the heat must be transferred through many interfaces causing rapid decrease in heat transfer coefficient.

Example – Stone Wool Insulation

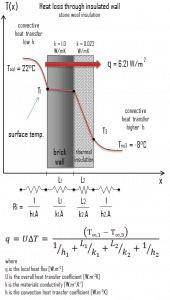

A major source of heat loss from a house is through walls. Calculate the rate of heat flux through a wall 3 m x 10 m in the area (A = 30 m2). The wall is 15 cm thick (L1), and it is made of bricks with thermal conductivity of k1 = 1.0 W/m.K (poor thermal insulator). Assume that the indoor and the outdoor temperatures are 22°C and -8°C, and the convection heat transfer coefficients on the inner and the outer sides are h1 = 10 W/m2K and h2 = 30 W/m2K, respectively. These convection coefficients strongly depend on ambient and interior conditions (wind, humidity, etc.).

A major source of heat loss from a house is through walls. Calculate the rate of heat flux through a wall 3 m x 10 m in the area (A = 30 m2). The wall is 15 cm thick (L1), and it is made of bricks with thermal conductivity of k1 = 1.0 W/m.K (poor thermal insulator). Assume that the indoor and the outdoor temperatures are 22°C and -8°C, and the convection heat transfer coefficients on the inner and the outer sides are h1 = 10 W/m2K and h2 = 30 W/m2K, respectively. These convection coefficients strongly depend on ambient and interior conditions (wind, humidity, etc.).

- Calculate the heat flux (heat loss) through this non-insulated wall.

- Now assume thermal insulation on the outer side of this wall. Use stone wool insulation 10 cm thick (L2) with the thermal conductivity of k2 = 0.022 W/m.K and calculate the heat flux (heat loss) through this composite wall.

Solution:

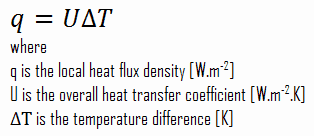

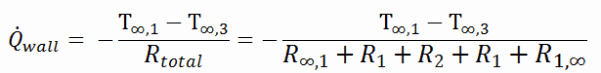

As was written, many heat transfer processes involve composite systems and even involve a combination of conduction and convection. It is often convenient to work with an overall heat transfer coefficient, known as a U-factor with these composite systems. The U-factor is defined by an expression analogous to Newton’s law of cooling:

The overall heat transfer coefficient is related to the total thermal resistance and depends on the geometry of the problem.

- bare wall

Assuming one-dimensional heat transfer through the plane wall and disregarding radiation, the overall heat transfer coefficient can be calculated as:

The overall heat transfer coefficient is then:

U = 1 / (1/10 + 0.15/1 + 1/30) = 3.53 W/m2K

The heat flux can be then calculated simply as:

q = 3.53 [W/m2K] x 30 [K] = 105.9 W/m2

The total heat loss through this wall will be:

qloss = q . A = 105.9 [W/m2] x 30 [m2] = 3177W

- composite wall with thermal insulation

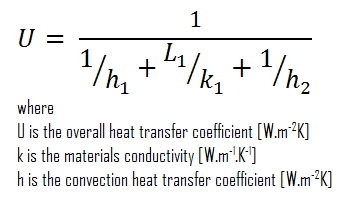

Assuming one-dimensional heat transfer through the plane composite wall, no thermal contact resistance, and disregarding radiation, the overall heat transfer coefficient can be calculated as:

The overall heat transfer coefficient is then:

The overall heat transfer coefficient is then:

U = 1 / (1/10 + 0.15/1 + 0.1/0.022 + 1/30) = 0.207 W/m2K

The heat flux can be then calculated simply as:

q = 0.207 [W/m2K] x 30 [K] = 6.21 W/m2

The total heat loss through this wall will be:

qloss = q . A = 6.21 [W/m2] x 30 [m2] = 186 W

As can be seen, adding a thermal insulator causes a significant decrease in heat losses. It must be added that adding the next layer of the thermal insulator does not cause such high savings. This can be better seen from the thermal resistance method, which can be used to calculate the heat transfer through composite walls. The rate of steady heat transfer between two surfaces is equal to the temperature difference divided by the total thermal resistance between those two surfaces.