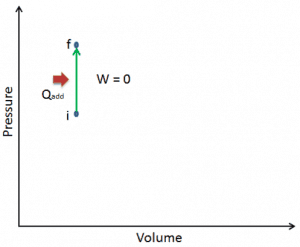

The case n ➝ ∞ corresponds to an isochoric (constant-volume) process for an ideal gas and a polytropic process. In contrast to the adiabatic process, in which n = and a system exchanges no heat with its surroundings (Q = 0; W≠0), in an isochoric process, there is a change in the internal energy (due to ∆T≠0) and therefore ΔU ≠ 0 (for ideal gases) and (Q ≠ 0; W=0).

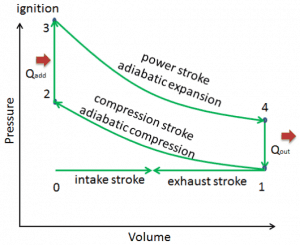

In engineering internal combustion engines, isochoric processes are very important for their thermodynamic cycles (Otto and Diesel cycle). Therefore the study of this process is crucial for automotive engineering.

Isochoric Process and the First Law

The classical form of the first law of thermodynamics is the following equation:

dU = dQ – dW

In this equation, dW is equal to dW = pdV and is known as the boundary work. Then:

dU = dQ – pdV

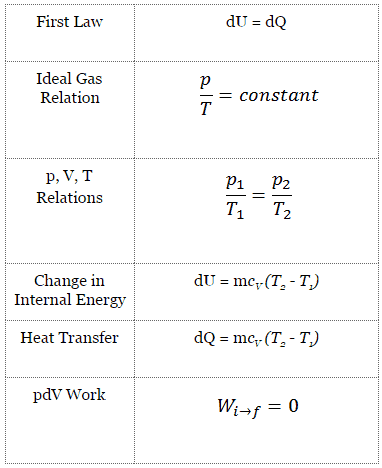

In the isochoric process and the ideal gas, all heat added to the system will increase the internal energy.

Isochoric process (pdV = 0):

dU = dQ (for ideal gas)

Isochoric Process – Ideal Gas Equation

See also: What is an Ideal Gas

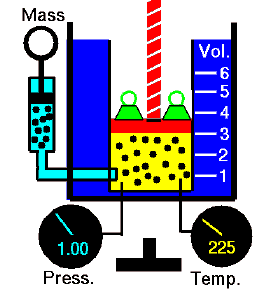

Let assume an isochoric heat addition in an ideal gas. In an ideal gas, molecules have no volume and do not interact. According to the ideal gas law, pressure varies linearly with temperature and quantity and inversely with volume.

Let assume an isochoric heat addition in an ideal gas. In an ideal gas, molecules have no volume and do not interact. According to the ideal gas law, pressure varies linearly with temperature and quantity and inversely with volume.

pV = nRT

where:

- p is the absolute pressure of the gas

- n is the amount of substance

- T is the absolute temperature

- V is the volume

- R is the ideal, or universal, gas constant, equal to the product of the Boltzmann constant and the Avogadro constant,

In this equation, the symbol R is the universal gas constant that has the same value for all gases—namely, R = 8.31 J/mol K.

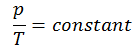

The isochoric process can be expressed with the ideal gas law as:

or

On a p-V diagram, the process occurs along a horizontal line with the equation V = constant.

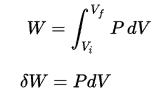

Pressure-volume work by the closed system is defined as:

Since the process is isochoric, dV = 0, the pressure-volume work is equal to zero. According to the ideal gas model, the internal energy can be calculated by:

∆U = m cv ∆T

where the property cv (J/mol K) is referred to as specific heat (or heat capacity) at a constant volume because under certain special conditions (constant volume), it relates the temperature change of a system to the amount of energy added by heat transfer.

Since there is no work done by or on the system, the first law of thermodynamics dictates ∆U = ∆Q. Therefore:

Q = m cv ∆T

See also: Specific Heat at Constant Volume and Constant Pressure

See also: Mayer’s formula

Guy-Lussac’s Law

Guy-Lussac’s Law or the Pressure Law, one of the gas laws, states that:

The pressure is directly proportional to the Kelvin temperature for a fixed mass of gas at constant volume.

That means that, for example, if you double the temperature, you will double the pressure. If you halve the temperature, you will halve the pressure.

You can express this mathematically as:

p = constant . T

Yes, it seems to be identical to the isochoric process of an ideal gas. These results are fully consistent with the ideal gas law, which determinates that the constant is equal to nR/V. If you rearrange the pV = nRT equation by dividing both sides by V, you will obtain:

p = nR/V . T

where nR/V is constant and:

- p is the absolute pressure of the gas

- n is the amount of substance

- T is the absolute temperature

- V is the volume

- R is the ideal, or universal, gas constant, equal to the product of the Boltzmann constant and the Avogadro constant

Example of Isochoric Process – Isochoric Heat Addition

Let assume the Otto Cycle, which is one of the most common thermodynamic cycles found in automobile engines. This cycle assumes that the heat addition occurs instantaneously (between 2 → 3) while the piston is at the top dead center. This process is considered to be isochoric.

Let assume the Otto Cycle, which is one of the most common thermodynamic cycles found in automobile engines. This cycle assumes that the heat addition occurs instantaneously (between 2 → 3) while the piston is at the top dead center. This process is considered to be isochoric.

Processes 2 → 3, and 4 → 1 are isochoric processes. The heat is transferred into the system between 2 → 3 and out of the system between 4 → 1. During these processes, no work is done on the system or extracted from the system. The isochoric process 2 → 3 is intended to represent the ignition of the fuel-air mixture and the subsequent rapid burning.