Source: wikipedia.org

Cloud chambers, also known as Wilson cloud chambers, are particle detectors essential devices in early nuclear and particle physics research. Cloud chambers, one of the most simple instruments to study elementary particles, have been substituted by more modern detectors in actual research, but they remain a very interesting pedagogical apparatus.

Cloud Chamber – Principle of Operation

The fundamental principle behind them is the supersaturation of a vapor substance, a state in which the air, or any other gas, contains more vapor of that substance than it can hold in a stable equilibrium. An energetic charged particle (for example, an alpha or beta particle) interacts with the vapor mixture. It creates a track of ions, which under supersaturation conditions act as condensation nuclei around which a mist-like trail of small droplets forms if the gas mixture is at the point of condensation.

These droplets are visible as a “cloud” track that persist for several seconds while the droplets fall through the vapor. The condensation of the vapor on these nuclei allows visual identification of the trajectories of the particles, leading to a straightforward study of their properties. The air inside the sealed device was saturated with water vapor in Wilson’s original chamber. Then a diaphragm was used to expand the air inside the chamber (adiabatic expansion), cooling the air and condensing water vapor. Hence the name expansion cloud chamber is used. The first antiparticle, the positron, the muon, and the first strange particle, the kaon, were identified using a cloud chamber.

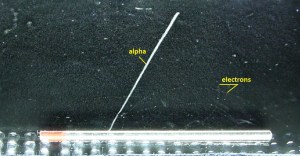

Diffusion Cloud Chamber

Although diffusion cloud chambers were never broadly used in nuclear and particle physics research, being easy to build and carry, they remain interesting educational instruments. A diffusion cloud chamber differs from the expansion cloud chamber in that it is continuously sensitized to radiation. The bottom must be cooled to a rather low temperature, generally colder than −26 °C (−15 °F). Instead of water vapor, alcohol is used because of its lower freezing point. Nowadays, they are an easy way of learning about and visualizing elementary particles and radiation.

Ionization and Track Information

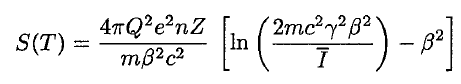

It must be emphasized that drops in these devices form tracks that grow on ions created by the passage of ionizing particles. Thus, this ionization process must be analyzed. Each type of particle interacts differently. Therefore knowledge of this interaction, how different particles deposit energy in the matter, and how much energy particles deposit is fundamental for our understanding of the problem. For example, charged particles with high energies can directly ionize atoms. Alpha particles are fairly massive and carry a double positive charge, so they tend to travel only a short distance and do not penetrate very far into a tissue, if at all. However, alpha particles will deposit their energy over a smaller volume (possibly only a few cells if they enter a body) and cause more damage to those few cells. As a result, alpha particles leave short but significant traces in the chamber.

Beta particles (electrons) are much smaller than alpha particles and carry a single negative charge. They are more penetrating than alpha particles and can travel several meters but deposit less energy at any point along their paths than alpha particles. Therefore, beta particles leave a longer but less visible trace in the chamber.

If a magnetic field is applied across the cloud chamber, positively and negatively charged particles will curve in opposite directions, according to the Lorentz force law.

According to experimental data, the specific ionization dN/dx in cloud chambers, defined as the mean number of ions produced per unit of length by a passing particle, is well described as a first approximation both for electrons and for more massive particles by the Bethe equation.

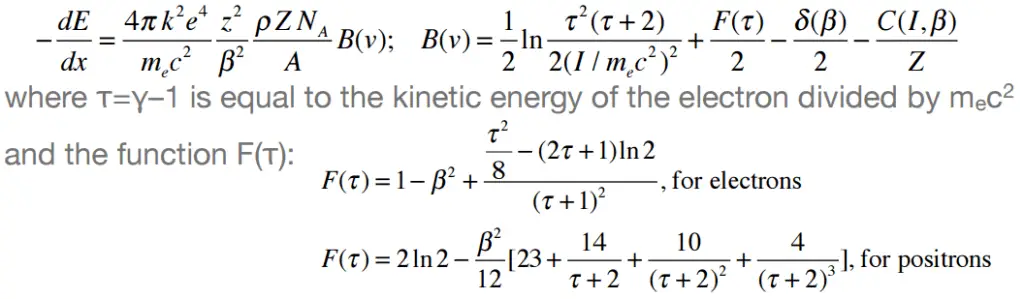

Stopping Power – Bethe Formula

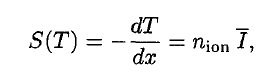

A convenient variable that describes the ionization properties of the surrounding medium is the stopping power. The linear stopping power of the material is defined as the ratio of the differential energy loss for the particle within the material to the corresponding differential path length:

where T is the kinetic energy of the charged particle, nion is the number of electron-ion pairs formed per unit path length, and I denotes the average energy needed to ionize an atom in the medium. For charged particles, S increases as the particle velocity decreases. The classical expression describing the specific energy loss is the Bethe formula. The non-relativistic formula was found by Hans Bethe in 1930. The relativistic version (see below) was also found by Hans Bethe in 1932.

In this expression, m is the rest mass of the electron, β equals v/c, which expresses the particle’s velocity relative to the speed of light, γ is the Lorentz factor of the particle, Q equals its charge, Z is the atomic number of the medium and n is the density of the atoms in the volume. For non-relativistic particles (heavy charged particles are mostly non-relativistic), dT/dx depends on 1/v2. This can be explained by the greater time the charged particle spends in the negative field of the electron when the velocity is low.

The nature of the interaction of beta radiation with matter is different from alpha radiation, although beta particles are also charged particles. Beta particles have a much lower mass and reach mostly relativistic energies than alpha particles. Their mass is equal to the mass of the orbital electrons with which they are interacting. Unlike the alpha particle, a much larger fraction of its kinetic energy can be lost in a single interaction. Since the beta particles mostly reach relativistic energies, the non-relativistic Bethe formula cannot be used. For high-energy electrons, a similar expression has also been derived by Bethe to describe the specific energy loss due to excitation and ionization (the “collisional losses”).

Moreover, beta particles can interact via electron-nuclear interaction (elastic scattering off nuclei), which can significantly change the direction of a beta particle. Therefore their path is not so straightforward. The beta particles follow a very zig-zag path through absorbing material, and this resulting path of a particle is longer than the linear penetration (range) into the material.

Beta particles also differ from other heavy charged particles in the fraction of energy lost by the radiative process known as the bremsstrahlung. From classical theory, when a charged particle is accelerated or decelerated, it must radiate energy, and the deceleration radiation is known as the bremsstrahlung (“braking radiation”).

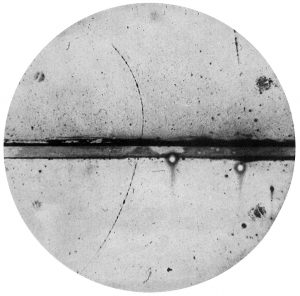

Cloud Chamber and Discovery of Positron

Positrons are positively charged (+1e), almost massless particles. Their rest mass equals 9.109 × 10−31 kg (510.998 keV/c2) (approximately 1/1836 that of the proton).

Like all elementary particles, electrons exhibit properties of both particles and waves: they can collide with other particles and diffract like light. The original idea for antiparticles came from a relativistic wave equation developed in 1928 by the English scientist P. A. M. Dirac (1902-1984). He realized that his relativistic version of the Schrödinger wave equation for electrons predicted the possibility of antielectrons. These were discovered by Paul Dirac and Carl D. Anderson in 1932 and named positrons. They studied cosmic-ray collisions via a cloud chamber – a particle detector in which moving electrons (or positrons) leave behind trails as they move through the gas. Positron paths in a cloud chamber trace the same helical path as an electron but rotate in the opposite direction for the magnetic field direction due to their having the same magnitude of charge-to-mass ratio but with opposite charge and, therefore, opposite signed charge-to-mass ratios. Although Dirac did not himself use the term antimatter, its use follows naturally enough from antielectrons, antiprotons, etc.

Bubble Chamber

Bubble chambers are particle detectors that are based on a similar principle as cloud chambers. In the bubble chamber, the tracks of subatomic particles are revealed as trails of bubbles in a liquid heated to just below its boiling point, usually liquid hydrogen. Bubble chambers can be made physically larger than cloud chambers, and since they are filled with much-denser liquid material, they reveal the tracks of much more energetic particles. An energetic charged particle (for example, an alpha or beta particle) interacts with the liquid, and the liquid enters into a superheated, metastable phase. Around the ionization track, the liquid vaporizes, forming microscopic bubbles. Bubble density around a track is proportional to a particle’s energy loss.

It must be emphasized that bubbles in these devices form tracks that grow on ions created by the passage of ionizing particles. Thus, this ionization process must be analyzed. Each type of particle interacts differently. Therefore knowledge of this interaction, how different particles deposit energy in the matter, and how much energy particles deposit is fundamental for our understanding of the problem. For example, charged particles with high energies can directly ionize atoms. Alpha particles are fairly massive and carry a double positive charge, so they tend to travel only a short distance and do not penetrate very far into a tissue, if at all. However, alpha particles will deposit their energy over a smaller volume (possibly only a few cells if they enter a body) and cause more damage to those few cells. As a result, alpha particles leave short but significant traces in the chamber.

Beta particles (electrons) are much smaller than alpha particles and carry a single negative charge. They are more penetrating than alpha particles and can travel several meters but deposit less energy at any point along their paths than alpha particles. Therefore, beta particles leave a longer but less visible trace in the chamber.

If a magnetic field is applied across the cloud chamber, positively and negatively charged particles will curve in opposite directions, according to the Lorentz force law.