In general,

nuclear fission results in the release of

enormous quantities of energy. The amount of energy

depends strongly on the nucleus to be fissioned and depends strongly on an incident neutron’s kinetic energy.

The total energy released in a reactor is

about 210 MeV per

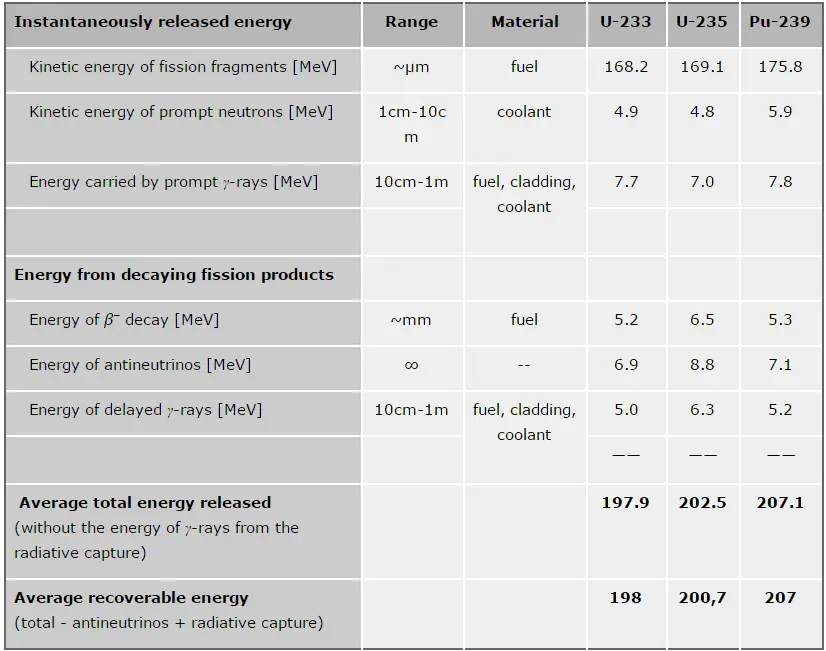

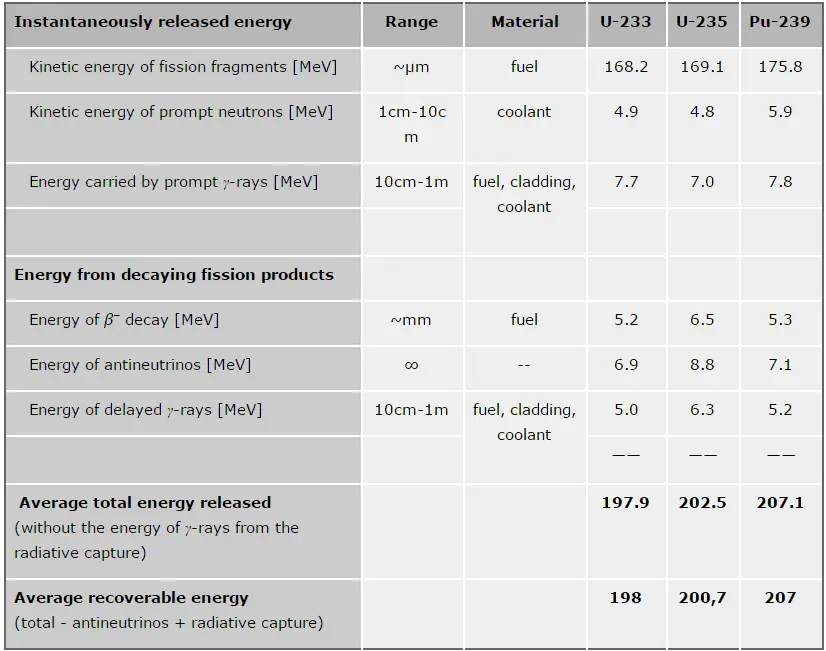

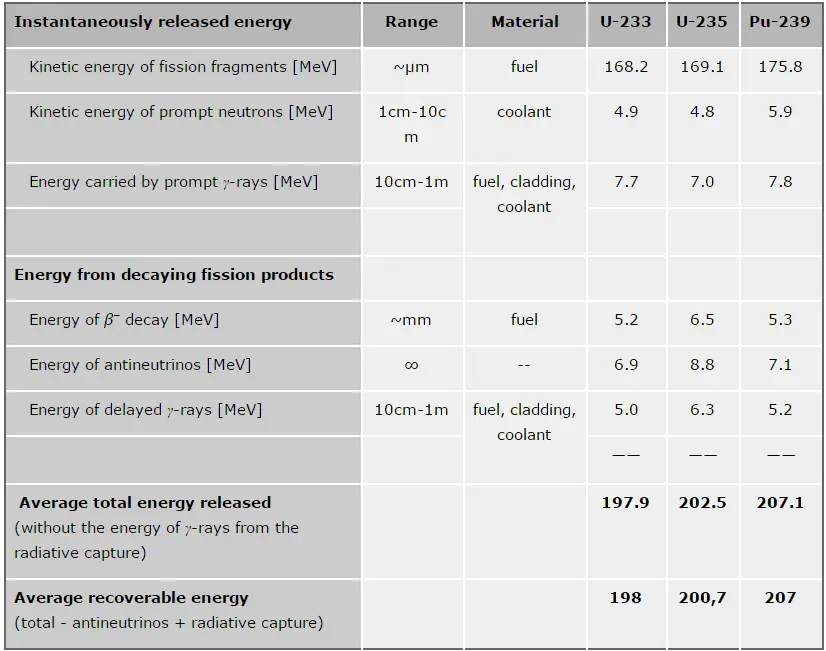

235U fission, distributed as shown in the table.

To calculate the power of a reactor, it is necessary to identify the individual components of this energy precisely. At first, it is important to distinguish between the total energy released and the energy that can be recovered in a reactor.

The total energy released in fission can be calculated from binding energies of the initial target nucleus to be fissioned and binding energies of fission products. But not all the total energy can be recovered in a reactor. For example, about 10 MeV is released in the form of neutrinos (in fact, antineutrinos). Since the neutrinos are weakly interacting (with an extremely low cross-section of any interaction), they do not contribute to the energy that can be recovered in a reactor.

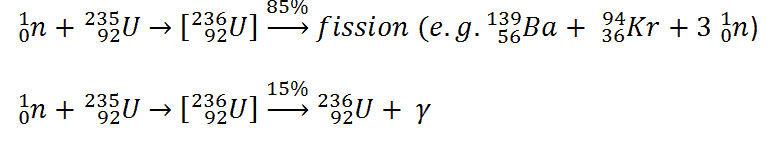

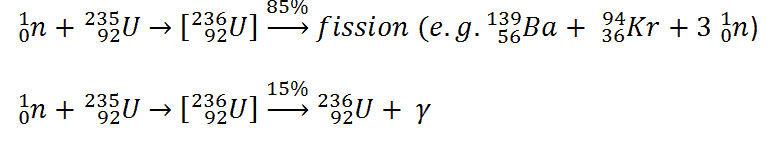

To understand this issue, we must first investigate a typical fission reaction such as the one listed below.

Energy Release per Component

Using the above reaction, we can identify and describe almost all the individual components of the total energy released during the fission reaction.

Kinetic energy of fission fragments

As can be seen when the

compound nucleus splits, it breaks into two

fission fragments. In most cases, the resultant fission fragments have masses that vary widely, but the most probable pair of fission fragments for the

thermal neutron-induced fission of the

235U have masses of about 94 and 139.

The largest part of the energy produced during fission (about 80 % or about 170 MeV or about 27 picojoules) appears as kinetic energy of the fission fragments. The initial velocity of these fission fragments is of the order of 10 000 km per second. The fission fragments interact strongly (intensely) with the surrounding atoms or molecules traveling at high speed, causing them to ionize. The creation of ion pairs requires energy, which is lost from the kinetic energy of the charged fission fragment, causing it to decelerate. The positive ions and free electrons created by the passage of the charged fission fragment will then reunite, releasing energy in the form of heat (e.g.,, vibrational energy or rotational energy of atoms).

The range of these massive, highly charged particles in the fuel is of the order of micrometers so that the recoil energy is effectively deposited as heat at the point of fission. This is the principle of how fission fragments heat fuel in the reactor core.

See also: Interaction of Heavy Charged Particles with Matter

Kinetic energy of prompt neutrons.

Prompt neutrons are emitted directly from fission, and they are emitted within a very short time of

about 10-14 second. Usually, more than

99 percent of the fission neutrons are

prompt neutrons. Still, the exact fraction is dependent on the nuclide to be fissioned and is also dependent on an incident neutron energy (usually increases with energy).

For example, fission of 235U by thermal neutron yields 2.43 neutrons, of which 2.42 neutrons are the prompt neutrons, and 0.01585 neutrons (0.01585/2.43=0.0065=ß) are the delayed neutrons. Almost all prompt fission neutrons have energies between 0.1 MeV and 10 MeV. The mean neutron energy is about 2 MeV. The most probable neutron energy is about 0.7 MeV.

Most of this energy is deposited in the coolant (moderator) because the water has the highest macroscopic slowing down power (MSDP) of the materials that are in a reactor core (PWR). The range of neutrons in a reactor depends strongly on certain reactor types. In the case of PWRs, it is usually of the order of centimeters.

Energy carried by prompt γ-rays.

With the

prompt neutrons prompt gamma rays are associated.

Most prompt gamma rays are emitted after prompt neutrons. The fission reaction releases approximately

~7 MeV in prompt gamma rays.

The gamma rays are well attenuated by high-density and high Z materials. In a reactor core, the largest share of the energy will be deposited in the fuel containing uranium dioxide. Still, a significant share of the energy will also be deposited in the fuel cladding and the coolant (moderator).

The range of gamma rays in a reactor varies according to the initial energy of the gamma-ray. It can be stated the most gammas in a reactor have ranged from 10cm-1m.

Energy of β− decay.

About 6 MeV of fission energy is in the form of

kinetic energy of electrons (

beta particles). The fission fragments are

neutron-rich nuclei, and therefore they usually undergo

beta decay to stabilize themselves. Beta particles deposit their energy essentially

in the fuel element, within about 1 mm of the fission fragment.

Energy of antineutrinos

Antineutrinos are produced in a

negative beta decay. A

nuclear reactor occurs especially the β− decay because the common feature of the

fission fragments is an

excess of neutrons. The existence of emission of antineutrinos and their

extremely low cross-section for any interaction leads to a very interesting phenomenon. Roughly

about 5% of released energy per one fission is

radiated away from the reactor in the form of antineutrinos.

For a typical nuclear reactor with thermal power of 3000 MWth (~1000MWe of electrical power), the total power produced is higher, approximately 3150 MW, of which 150 MW is radiated away into space antineutrino radiation. This amount of energy is forever lost because antineutrinos can penetrate all reactor materials without any interaction.

In fact, a common statement in physics texts is that the mean free path of a neutrino is approximately a light-year of lead. Moreover, a neutrino of moderate energy can easily penetrate a thousand light-years of lead (according to J. B. Griffiths).

Energy of delayed γ-rays.

The fission fragments are

neutron-rich and

very unstable nuclei. These nuclei undergo

many beta decays to stabilize themselves.

Gamma rays usually

accompany beta decay. Their energy is transferred as heat to the surrounding material, similarly to the energy carried by

prompt γ-rays.

Energy of γ-rays from radiative capture

A fraction of the

neutron absorption reactions result in

radiative capture followed by

gamma-ray emission, producing on average

about 7 MeV per fission in the form of energetic

gamma rays. Their energy is transferred as heat to the surrounding material, similarly to the energy carried by prompt γ-rays.

Energy Release in a Reactor

The total energy released in a reactor is about 210 MeV per 235U fission, distributed as shown in the table. In a reactor, the average recoverable energy per fission is about 200 MeV, the total energy minus the energy of antineutrinos radiated away. This means that about 3.1⋅1010 fissions per second are required to produce a power of 1 W. Since 1 gram of any fissile material contains about 2.5 x 1021 nuclei, the fissioning of 1 gram of fissile material yields about 1 megawatt-day (MWd) of heat energy.

As can be seen from the description of the individual components of the total energy released during the fission reaction, there is a significant amount of energy generated outside the nuclear fuel (outside fuel rods). Especially the kinetic energy of prompt neutrons is largely generated in the coolant (moderator). This phenomenon needs to be included in the nuclear calculations.

For LWR, it is generally accepted that about 2.5% of total energy is recovered in the moderator. This fraction of energy depends on the materials, their arrangement within the reactor, and thus on the reactor type.

See previous:

Critical Energy

See above:

Nuclear Fission

See next:

Fission Fragments