Lead, lead-bismuth eutectic, and other metals have been proposed and occasionally used. The lead-cooled fast reactor is a nuclear reactor design that features a fast neutron spectrum and molten lead or lead-bismuth eutectic coolant. Lead-Bismuth Eutectic or LBE is a eutectic alloy of lead (44.5%) and bismuth (55.5%). Molten lead or lead-bismuth eutectic can be used as the primary coolant because lead and bismuth have low neutron absorption and relatively low melting points.

Melting and boiling points of lead and lead-bismuth eutectic mixture are:

- lead

- melting point – 327.5°C

- boiling point – 1749°C

- lead-bismuth – a eutectic mixture

- melting point – 123.5°C

- boiling point – 1670°C

Source: wikipedia.org

Compared to sodium-based liquid metal coolants such as liquid sodium or NaK, lead-based coolants have significantly higher boiling points, meaning a reactor can be operated without the risk of coolant boiling at much higher temperatures. Lead and LBE also do not react readily with water or air, unlike sodium and NaK, which ignite spontaneously in air and react explosively with water. Due to its denseness and high atomic number, lead and bismuth are also excellent gamma radiation shields while simultaneously virtually transparent to neutrons.

On the other hand, lead, and LBE coolants are more corrosive to steel than sodium or NaK eutectic alloy. This and the very high density of lead puts an upper limit on the coolant flow velocity through the reactor due to safety considerations. Furthermore, the higher melting points of lead and LBE (327 °C and 123.5 °C, respectively) may mean that the solidification of the coolant may be a greater problem when the reactor is operated at lower temperatures.

Properties of Liquid Metals

Properties of Liquid Metals

In physics, liquid metal consists of alloy with very low melting points, which form a eutectic that is liquid at room temperature. In reactor engineering, liquid metals are alloys with low melting points allowing for reactor coolant to be liquid in operating range of temperatures (usually above the room temperature).

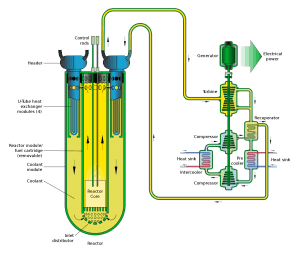

Liquid metals can be used as a reactor coolant because they have excellent heat transfer properties and can be employed in low-pressure systems, as is the case of sodium-cooled fast reactors (SFRs). The unique feature of metals as far as their structure is concerned is the presence of charge carriers, specifically free electrons, giving them high electrical conductivity high thermal conductivity. The use of liquid metal coolants made it possible to provide a high rate of heat transfer in power plants as well as the temperatures of working surfaces of their constructions close to coolant temperature.

Moreover, liquid metals used in reactor engineering are very weak absorbers of neutrons, allowing liquid metal reactors to operate with a fast neutron spectrum. A liquid metal fast reactor is a high power density reactor, which does not need a neutron moderator.

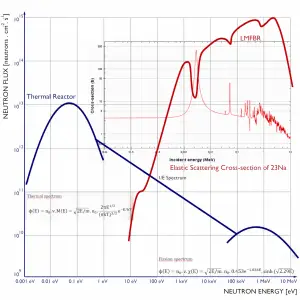

The main differences between thermal and fast reactors are, of course, in neutron cross-sections that exhibit significant energy dependency. It can be characterized by the capture-to-fission ratio, which is lower in fast reactors. There is also a difference in the number of neutrons produced per one fission, which is higher in fast reactors than in thermal reactors. These very important differences are caused primarily by differences in neutron fluxes. Therefore, it is important to know detailed neutron energy distribution in a reactor core.

The disadvantage of many liquid metals is their high chemical activity at interaction with oxygen, water, and structural materials, which may cause heat transfer deterioration in the plant under certain conditions.