In general, a nuclear reactor is a key device of nuclear power plants, nuclear research facilities, or nuclear-propelled ships. The main purpose of the nuclear reactor is to initiate and control a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The most common nuclear reactors are light water reactors (LWR) that are based on the uranium fuel cycle and use an enriched uranium fuel (~4% of U-235) as a fresh fuel. During the fuel burning, the content of the U-235 decreases, and the content of the plutonium increases (up to ~1% of Pu ). Currently, these reactors provide almost 90% of the world’s nuclear electricity generating capacity.

Thorium reactors are based on the thorium fuel cycle and use thorium 232 as a fertile material. During the fuel burning, thorium 232 transforms into a fissile uranium 233. Unlike natural uranium, natural thorium contains only trace amounts of fissile material (such as thorium 231), which are insufficient to initiate and sustain the nuclear chain reaction. Therefore, additional fissile material is necessary to initiate the fuel cycle.

According to proponents, the thorium fuel cycle offers several potential advantages over a uranium fuel cycle, including thorium’s greater abundance, better physical and nuclear properties (e.g., the lower capture-to-fission ratio for thermal neutrons), reduced plutonium and actinide production, and better resistance to nuclear weapons proliferation when used in traditional light water reactors.

See also: Thorium vs. Uranium

On the other hand, thorium is “only” a fertile material, and the main problem can be directly in the breeding of fissile uranium 233. If 232Th is loaded in the nuclear reactor, the nuclei of 232Th absorb a neutron and become nuclei of 233Th. The half-life of 233Th is approximately 21.8 minutes. 233Th decays (negative beta decay) to 233Pa (protactinium), whose half-life is 26.97 days. 233Pa decays (negative beta decay) to 233U. Therefore, proposed reactor designs must attempt to physically isolate the protactinium from further neutron capture before beta decay can occur.

Types of Thorium Reactors

As for uranium-based reactors, the basic classification of thorium nuclear reactors is based upon the average energy of the neutrons, which cause the bulk of the fissions in the reactor core. From this point of view, nuclear reactors are divided into two categories:

- Thermal Reactors. Almost all of the current reactors which have been built to date use thermal neutrons to sustain the chain reaction. These reactors contain neutron moderator that slows neutrons from fission until their kinetic energy is more or less in thermal equilibrium with the atoms (E < 1 eV) in the system.

- Fast Neutron Reactors. Fast reactors contain no neutron moderator and use less-moderating primary coolants because they use fast neutrons (E > 1 keV) to cause fission in their fuel.

In principle, all reactor types may be fuelled with thorium, but some are more suited to thorium fuel than others. As will be shown in further section, uranium 233 has very good parameters in the thermal spectrum. For fast spectrum, thorium is not ideal because its parameters are between uranium 235 and plutonium 239. It should be pointed out that uranium 233 has a high reproduction factor in the epithermal spectrum, compared with U-235 and Pu-239, making thorium an advantageous fuel for the reduced moderation epithermal LWRs.

According to the World Nuclear Association, there are seven types of reactors that can be designed to use thorium as a nuclear fuel. Six of these have all entered into operational service at some point (usually with uranium fuel). The most promising are, for example:

- Heavy water reactors (PHWRs). PHWRs (Pressurized Heavy Water Reactors) generally use natural uranium (0.7% U-235) or slightly enriched uranium oxide as fuel; hence they need a more efficient moderator, in this case, heavy water (D2O). Due to the favorable neutron management (very low parasitic capture) caused by online refueling and consequently reduced requirements for control poisons to compensate for excess reactivity, an application of thorium is possible, and these reactors attain a relatively high conversion factor.

- High-temperature gas-cooled reactors (HTRs). These reactors are well suited for thorium-based fuels in the form of robust ‘TRISO’ coated particles of thorium mixed with plutonium or enriched uranium.

- Molten salt reactors (MSRs, LFTRs). A molten salt reactor (MSR) is a class of generation IV nuclear fission reactor in which the primary nuclear reactor coolant, or even the fuel itself, is a molten salt mixture. Reactors containing molten thorium salt are called liquid fluoride thorium reactors (LFTR).

In general, using thorium-based fuel in light water reactors is possible but not so promising. BWR fuel assemblies can be flexibly designed in terms of rods with varying compositions (fissile content) and structural features enabling the fuel to experience more or less moderation (e.g., half-length fuel rods). Viable thorium fuels can be designed for also a PWR, though with less flexibility than for BWRs. Fuel needs to be in heterogeneous arrangements to achieve satisfactory fuel burnup.

Thorium Reactors – Advantages and Disadvantages

It is very difficult to explain the possible advantages and disadvantages. Some of the following points can be valid for one reactor design, and another point can be invalid for another thorium-based reactor. Therefore, be careful when you argue for or against thorium reactors.

Possible Advantages

- The abundance of Natural Thorium. Although the uranium resources may be very large, it is recognized that the thorium content of the earth’s crust (0.0006% vs. 0.00018%) is about three times larger, reflecting its longer half-life. On the other hand, due to the low demand for thorium, the known reserves for uranium and thorium are both nearly identical.

- Neutronic and Thermal Parameters. For a thermal neutron spectrum (E < 1 eV) and the thorium-based fuel, the reproduction factor is considerably larger than for uranium-based fuel. Due to the very low capture-to-fission ratio, the reproduction factor for uranium 233 is about η = 2.25. From this point of view, is thorium fuel cycle is very promising. Another advantage can be the favorable physical and chemical properties of thorium dioxide. Compared to the predominant reactor fuel, uranium dioxide (UO2), thorium dioxide (ThO2) has a higher melting point, higher thermal conductivity, and lower coefficient of thermal expansion. In particular, the thermal conductivity is important since it leads to a lower fuel pellets temperature.

- Lower Production of Transuranic Elements. The transuranic elements (plutonium and other minor actinides) are the major health concern of long-term (on the order of roughly 103 to 106 years) nuclear waste. In uranium-based fuels, only a single neutron capture in uranium 238 is sufficient to produce these transuranic elements, whereas five captures are generally necessary to do so from thorium 232. Therefore, thorium is a potentially attractive alternative to uranium-based fuels because the production of transuranic elements is significantly lower.

- Proliferation Resistance. Concerning proliferation significance, thorium-based fuels are generally accepted as proliferation-resistant compared to uranium-based fuels. This comes mostly from the fact that almost no plutonium is produced. In fact, if plutonium is used as the fissile component of thorium fuel, the plutonium is efficiently consumed. Moreover, the uranium 233 produced in thorium fuels is significantly contaminated with uranium 232 in proposed power reactor designs. 232U has a relatively short half-life of 68.9 years, and therefore the specific activity of 232U is much higher than the specific activity of the isotope 238U. In addition, the decay chain of 232U produces very penetrating gamma rays. The most important gamma emitter, accounting for about 85 percent of the total dose from 232U after 2 years, is thallium 208, which emits gamma rays of 2.6 MeV, which are very energetic and highly penetrating. These intense radiations make the handling of fissile 233U or reprocessed uranium contaminated with 232U far more dangerous than conventional fuels.

Possible Disadvantages

- Material Buckling. As was written, naturally occurring thorium is effectively mononuclidic of thorium 232, which is a fertile isotope. Therefore, another fissile material must be added to the initial fuel load to achieve criticality. This fact must be taken into account during considerations about possible advantages.

- The half-life of 233Pa. Thorium 232 is “only” a fertile material, and the main problem can be directly in the breeding of fissile uranium 233. If 232Th is loaded in the nuclear reactor, the nuclei of 232Th absorb a neutron and become nuclei of 233Th. The half-life of 233Th is approximately 21.8 minutes. 233Th decays (negative beta decay) to 233Pa (protactinium), whose half-life is 26.97 days. 233Pa decays (negative beta decay) to 233U. Therefore, proposed reactor designs must attempt to physically isolate the protactinium from further neutron capture before beta decay can occur. 233Pa is a significant neutron absorber and, although it eventually breeds into fissile 235U, this requires two more neutron absorptions, which degrades neutron economy and increases the likelihood of transuranic production.

- Radiation Protection. 232U is produced from 232Th via specific (n,2n) reactions in which an incoming neutron knocks two neutrons out of a target nucleus. 232U has a relatively short half-life of 68.9 years, and therefore the specific activity of 232U is much higher than the specific activity of the isotope 238U. In addition, the decay chain of 232U produces very penetrating gamma rays. These gamma rays are hard to shield, requiring more expensive spent fuel handling and/or reprocessing.

- Delayed Neutrons. Another important aspect of reactor safety is the delayed neutron fraction. Despite the fact, the number of delayed neutrons per fission neutron is quite small (typically below 1%) and thus does not contribute significantly to the power generation, they play a crucial role in reactor control. They are essential from the point of view of reactor kinetics and reactor safety. The delayed neutron fraction is significantly lower for uranium 233 than for uranium 235. As a result, a reactor in which uranium 233 is the predominant isotope responds more rapidly and puts increased demands on the design of the control system.

What is Thorium

Thorium is a naturally-occurring chemical element with atomic number 90, which means there are 90 protons and 90 electrons in the atomic structure. The chemical symbol for thorium is Th. Thorium was discovered in 1828 by Norwegian mineralogist Morten Thrane Esmark. Joens Jakob Berzelius, the Swedish chemist, named it after Thor, the Norse god of thunder.

Thorium is a naturally-occurring element, and it is estimated to be about three times more abundant than uranium. Thorium is commonly found in monazite sands (rare earth metals containing phosphate minerals).

Thorium has 6 naturally occurring isotopes. All of these isotopes are unstable (radioactive), but only 232Th is relatively stable with a half-life of 14 billion years, which is comparable to the age of the Earth (~4.5×109 years). Isotope 232Th belongs to primordial nuclides, and natural thorium consists primarily of isotope 232Th. Other isotopes (230Th, 229Th, 228Th, 234Th, and 227Th) occur in nature as trace radioisotopes, which originate from the decay of 232Th, 235U, and 238U.

Thorium 232

Thorium 232, which alone makes up nearly all natural thorium, is the most common isotope of thorium in nature. This isotope has the longest half-life (1.4 x 1010 years) of all isotopes with more than 83 protons, and its half-life is considerably longer than the age of Earth. Therefore 232Th belongs to primordial nuclides.

232Th decays via alpha decay into 228Ra. 232Th occasionally decays by spontaneous fission with a very low probability of 1.1 x 10-9 %.

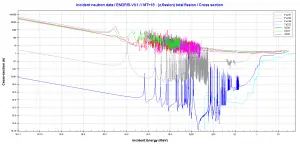

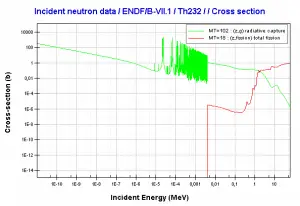

232Th is a fertile isotope. 232Th is not capable of undergoing a fission reaction after absorbing a thermal neutron. On the other hand, 232Th can be fissioned by fast neutron with energy higher than >1MeV. 232Th does not also meet alternative requirements to fissile materials. 232Th is not capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction because too many neutrons produced by fission of 232Th have lower energies than the original neutron.

Isotope 232Th is the key material in the thorium fuel cycle. Radiative capture of a neutron leads to the formation of fissile 233U. This process is called nuclear fuel breeding.

Conversion Factor for Thorium Reactor

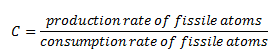

A quantity that characterizes this conversion of fertile into fissile material is known as the conversion factor. The conversion factor is defined as the ratio of fissile material created to fissile material consumed either by fission or absorption. If the ratio is greater than one, it is often referred to as the breeding ratio, for then the reactor is creating more fissile material than it is consuming.

When C is unity, one new atom is produced per one atom consumed. It seems fertile material can be converted in the reactor indefinitely without adding new fuel. Still, in real reactors, the content of fertile thorium 232 also decreases, and fission products with significant absorption cross-section accumulate in the fuel as fuel burnup increases.

The fertile-to-fissile conversion characteristics depend on the fuel cycle and the neutron energy spectrum. For a thermal neutron spectrum (E < 1 eV) and the uranium fuel cycle, fuel breeding (C>1) is not feasible, although η for both isotopes is greater than 2. This is due to the fact η is not large enough to compensate for the neutron leakage and its parasitic capture.

The situation is considerably better for a thermal neutron spectrum (E < 1 eV) and the thorium fuel cycle. Due to the very low capture-to-fission ratio, the reproduction factor for uranium 233 is about η = 2.25. From this point of view, is thorium fuel cycle is promising, and a thermal reactor of this type could successfully be made to breed.