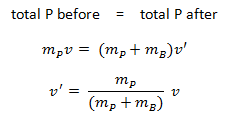

The vector sum of the momenta (momentum is equal to the mass of an object multiplied by its velocity) of all the objects of a system cannot be changed by interactions within the system. In classical mechanics, this law is implied by Newton’s laws. This principle is a direct consequence of Newton’s third law.

Let us assume the one-dimensional elastic collision of two billiard balls, ball A and ball B. We assume the net external force on this system of two balls is zero—that is, the only significant forces during the collision are the forces that each ball exerts on the other. According to Newton’s third law, the two forces are always equal in magnitude and opposite direction. Hence, the impulses that act on the two balls are equal and opposite, and the changes in momentum of the two balls are equal and opposite.

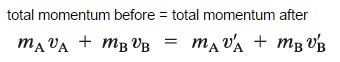

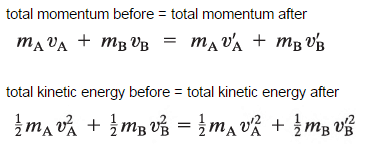

These two balls are moving with velocities vA and vB along the x-axis before the collision. After the collision, their velocities are v’A and v’B. The conservation of the total momentum demands that the total momentum before the collision is the same as the total momentum after the collision.

The law of conservation of linear momentum in words:

If no net external force acts on a system of particles, the total linear momentum of the system cannot change.

Conservation of Momentum and Energy in Collisions

The use of the conservation laws for momentum and energy is also very important in particle collisions. This is a very powerful rule because it can allow us to determine the results of a collision without knowing the details of the collision. The law of conservation of momentum states that the total momentum is conserved in the collision of two objects such as billiard balls. The assumption of momentum and kinetic energy conservation makes it possible to calculate the final velocities in two-body collisions. At this point, we have to distinguish between two types of collisions:

Elastic Collisions

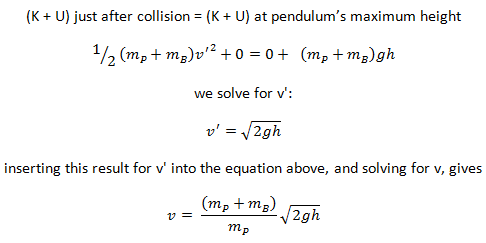

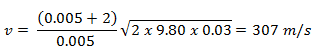

A perfectly elastic collision is defined as one in which there is no net conversion of kinetic energy into other forms (such as heat or noise). For the brief moment during which the two objects are in contact, some (or all) of the energy is stored momentarily in the form of elastic potential energy. But if we compare the total kinetic energy just before the collision with the total kinetic energy just after the collision, they are found to be the same. We say that the total kinetic energy is conserved.

- Large-scale interactions between satellites and planets are perfectly elastic, like the slingshot type gravitational interactions (also known as a planetary swing-by or a gravity-assist maneuver).

- Collisions between very hard spheres may be nearly elastic, so it is useful to calculate the limiting case of an elastic collision.

- Collisions in ideal gases approach perfectly elastic collisions, as scattering interactions of sub-atomic particles deflect by the electromagnetic force.

- Rutherford scattering is the elastic scattering of charged particles also by the electromagnetic force.

- A neutron-nucleus scattering reaction may also be elastic, but in this case, the neutron is deflected by a strong nuclear force.

Inelastic Collisions

An inelastic collision is when part of the kinetic energy is changed to some other form of energy in the collision. Any macroscopic collision between objects will convert some kinetic energy into internal energy and other forms of energy, so no large-scale impacts are perfectly elastic. For example, in collisions of common bodies, such as two cars, some energy is always transferred from kinetic energy to other forms of energy, such as thermal energy or energy of sound. The inelastic collision of two bodies always involves a loss in the kinetic energy of the system. The greatest loss occurs if the bodies stick together, in which case the collision is called a completely inelastic collision. Thus, the kinetic energy of the system is not conserved, while the total energy is conserved as required by the general principle of conservation of energy. Momentum is conserved in inelastic collisions, but one cannot track the kinetic energy through the collision since some of it is converted to other forms of energy.

In nuclear physics, an inelastic collision is when the incoming particle causes the nucleus to strike to become excited or break up. Deep inelastic scattering is a method of probing the structure of subatomic particles in much the same way as Rutherford probed the inside of the atom (see Rutherford scattering).

In nuclear reactors, inelastic collisions are of importance in the neutron moderation process. An inelastic scattering plays an important role in slowing down neutrons, especially at high energies and by heavy nuclei. Inelastic scattering occurs above threshold energy. This threshold energy is higher than the energy of the first excited state of the target nucleus (due to the laws of conservation), and it is given by the following formula:

Et = ((A+1)/A)* ε1

where Et is the inelastic threshold energy, and ε1 is the energy of the first excited state. Therefore, especially scattering data of 238U, a major component of nuclear fuel in commercial power reactors, is one of the most important data in the neutron transport calculations in the reactor core.

Conservation Laws in Nuclear Reactions

A nuclear reaction is considered to be the process in which two nuclear particles (two nuclei or a nucleus and a nucleon) interact to produce two or more nuclear particles or ˠ-rays (gamma rays). Thus, a nuclear reaction must cause a transformation of at least one nuclide to another. Sometimes if a nucleus interacts with another nucleus or particle without changing the nature of any nuclide, the process is referred to as a nuclear scattering rather than a nuclear reaction.

In analyzing nuclear reactions, we apply the many conservation laws. Nuclear reactions are subject to classical conservation laws for a charge, momentum, angular momentum, and energy (including rest energies). Not anticipated by classical physics, other conservation laws are electric charge, lepton number, and baryon number. Certain of these laws are obeyed under all circumstances, and others are not. We have accepted the conservation of energy and momentum. In all the examples given, we assume that the number of protons and the number of neutrons is separately conserved. We shall find circumstances and conditions in which this rule is not true. Where we are considering non-relativistic nuclear reactions, it is essentially true. However, we shall find that these principles must be extended when we consider relativistic nuclear energies or those involving weak interactions.

Some conservation principles have arisen from theoretical considerations, and others are just empirical relationships. Notwithstanding, any reaction not expressly forbidden by the conservation laws will generally occur, if perhaps at a slow rate. This expectation is based on quantum mechanics. Unless the barrier between the initial and final states is infinitely high, there is always a non-zero probability that a system will make the transition between them.

For the purposes of this article, it is sufficient to note four of the fundamental laws governing these reactions.

- Conservation of nucleons. The total number of nucleons before and after a reaction are the same.

- Conservation of charge. The sum of the charges on all the particles before and after a reaction are the same.

- Conservation of momentum. The total momentum of the interacting particles before and after a reaction is the same.

- Conservation of energy. Energy, including rest mass energy, is conserved in nuclear reactions.

Conservation of Momentum in Nuclear Reactions – Neutron Moderation

See also: Neutron Elastic Scattering

See also: Neutron Inelastic Scattering

See also: Neutron Moderators

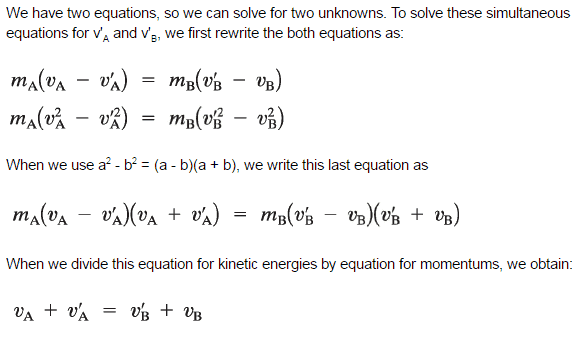

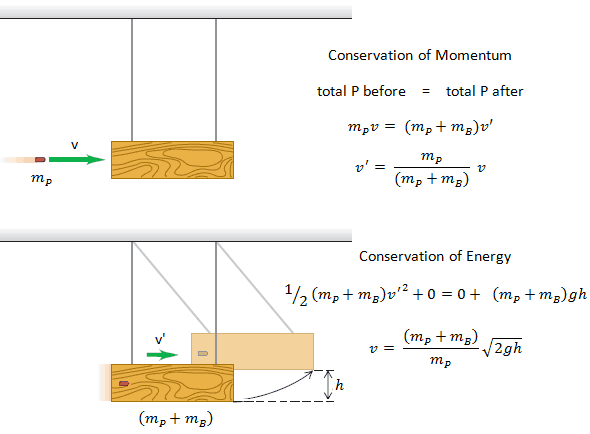

It is known the fission neutrons are of importance in any chain-reacting system. All neutrons produced by fission are born as fast neutrons with high kinetic energy. Before such neutrons can efficiently cause additional fissions, they must be slowed down by collisions with nuclei in the reactor’s moderator. The probability of the fission U-235 becomes very large at the thermal energies of slow neutrons. This fact implies the increase of the multiplication factor of the reactor (i.e., lower fuel enrichment is needed to sustain a chain reaction).

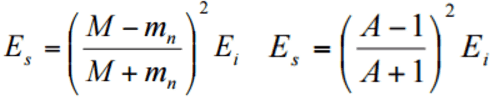

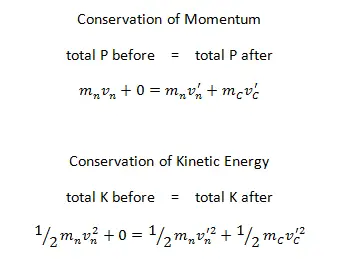

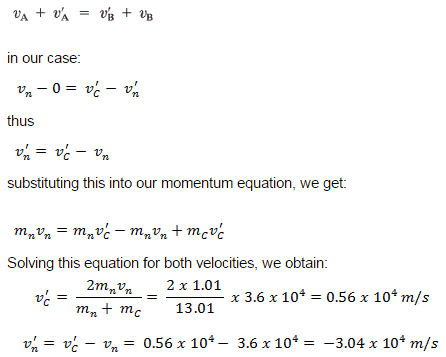

The neutrons released during fission with an average energy of 2 MeV in a reactor on average undergo many collisions (elastic or inelastic) before they are absorbed. During the scattering reaction, a fraction of the neutron’s kinetic energy is transferred to the nucleus. It is possible to derive the following equation for the mass of target or moderator nucleus (M), the energy of incident neutron (Ei), and the energy of scattered neutron (Es) using the laws of conservation of momentum and energy and the analogy of collisions of billiard balls for elastic scattering.

where A is the atomic mass number, in case of the hydrogen (A = 1) as the target nucleus, the incident neutron can be completely stopped. But this works when the direction of the neutron is completely reversed (i.e., scattered at 180°). In reality, the direction of scattering ranges from 0 to 180 °, and the energy transferred also ranges from 0% to maximum. Therefore, the average energy of the scattered neutron is taken as the average of energies with scattering angles 0 and 180°.

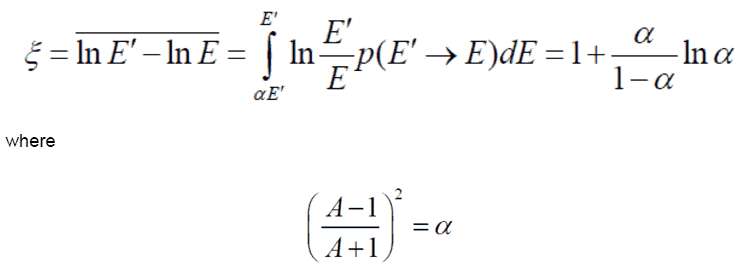

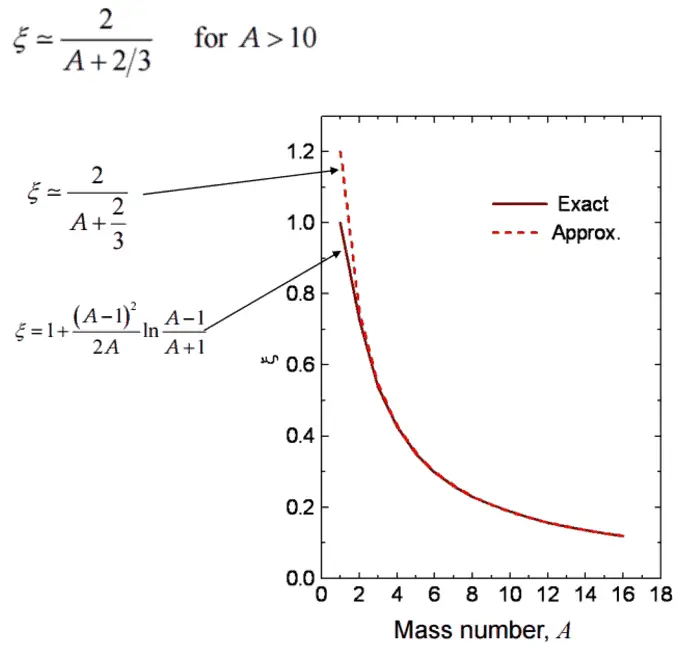

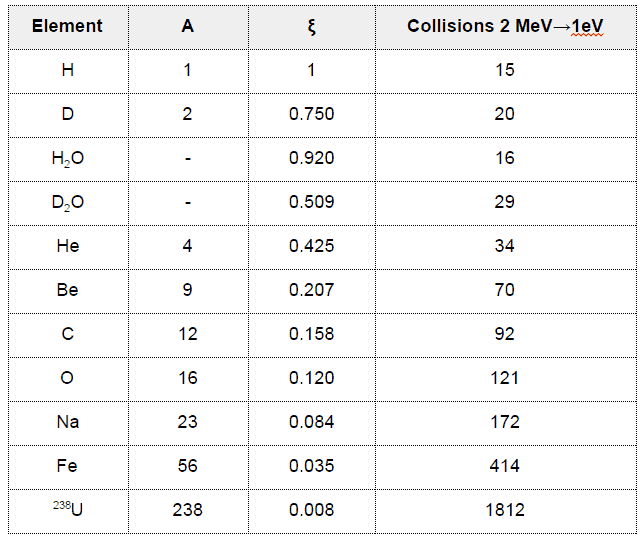

Moreover, it is useful to work with logarithmic quantities. Therefore one defines the logarithmic energy decrement per collision (ξ) as a key material constant describing energy transfers during a neutron slowing down. ξ is not dependent on energy, only on A and is defined as follows: For heavy target nuclei, ξ may be approximated by the following formula:

For heavy target nuclei, ξ may be approximated by the following formula: From these equations, it is easy to determine the number of collisions required to slow down a neutron from, for example from 2 MeV to 1 eV.

From these equations, it is easy to determine the number of collisions required to slow down a neutron from, for example from 2 MeV to 1 eV.

Example: Determine the number of collisions required for thermalization for the 2 MeV neutrons in the carbon.

ξCARBON = 0.158

N(2MeV → 1eV) = ln 2⋅106/ξ =14.5/0.158 = 92

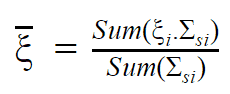

For a mixture of isotopes:

The momentum of a Photon

A photon, the quantum of electromagnetic radiation, is an elementary particle, the force carrier of the electromagnetic force. The modern photon concept was developed (1905) by Albert Einstein to explain the photoelectric effect, in which he proposed the existence of discrete energy packets during the transmission of light.

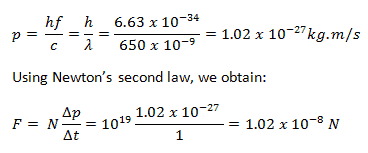

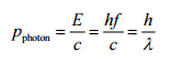

In 1916, Einstein extended his concept of light quanta (photons) by proposing that a quantum of light has linear momentum. Although a photon is massless, it has momentum, which is related to its energy E, frequency f, and wavelength by:

Thus, when a photon interacts with another object, energy and momentum are transferred, as if there were a collision between the photon and matter in the classical sense.

The momentum of a Photon – Compton Scattering

Source: hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu

The Compton formula was published in 1923 in the Physical Review. Compton explained that the X-ray shift is caused by the particle-like momentum of photons. Compton scattering formula is the mathematical relationship between the shift in wavelength and the scattering angle of the X-rays. In the case of Compton scattering, the photon of frequency f collides with an electron at rest. The photon bounces off the electron upon collision, giving up some of its initial energy (given by Planck’s formula E=hf). While the electron gains momentum (mass x velocity), the photon cannot lower its velocity. As a result of momentum conservation law, the photon must lower its momentum given by:

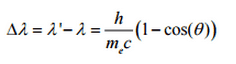

So the decrease in photon’s momentum must be translated into a decrease in frequency (increase in wavelength Δλ = λ’ – λ). The shift of the wavelength increased with scattering angle according to the Compton formula:

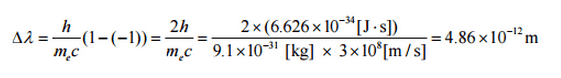

where λ is the initial wavelength of photon λ’ is the wavelength after scattering, h is the Planck constant = 6.626 x 10-34 J.s, me is the electron rest mass (0.511 MeV)c is the speed of light Θ is the scattering angle. The minimum change in wavelength (λ′ − λ) for the photon occurs when Θ = 0° (cos(Θ)=1) and is at least zero. The maximum change in wavelength (λ′ − λ) for the photon occurs when Θ = 180° (cos(Θ)=-1). In this case, the photon transfers to the electron as much momentum as possible. The maximum change in wavelength can be derived from the Compton formula:

The quantity h/mec is known as the Compton wavelength of the electron and is equal to 2.43×10−12 m.

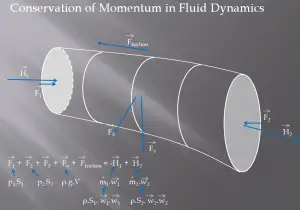

Conservation of Momentum in Fluid Dynamics

In general, the law of conservation of momentum or principle of momentum conservation states that the momentum of an isolated system is a constant. The vector sum of the momenta (momentum is equal to the mass of an object multiplied by its velocity) of all the objects of a system cannot be changed by interactions within the system. In classical mechanics, this law is implied by Newton’s laws.

In fluid dynamics, the analysis of motion is performed in the same way as in solid mechanics – using Newton’s laws of motion. As can be seen, moving fluids are exerting forces. The lift force on an aircraft is exerted by the air moving over the wing.

A jet of water from a hose exerts a force on whatever it hits. But here, it is not clear what mass of moving fluid we should use, and therefore it is necessary to use a different form of the equation.

Newton’s 2nd Law can be written:

We assume fluid to be both steady and incompressible. To determine the rate of change of momentum for a fluid, we will consider a stream tube (control volume) as we did for the Bernoulli equation. In this control volume, any change in momentum of the fluid within a control volume is due to the action of external forces on the fluid within the volume.

We assume fluid to be both steady and incompressible. To determine the rate of change of momentum for a fluid, we will consider a stream tube (control volume) as we did for the Bernoulli equation. In this control volume, any change in momentum of the fluid within a control volume is due to the action of external forces on the fluid within the volume.

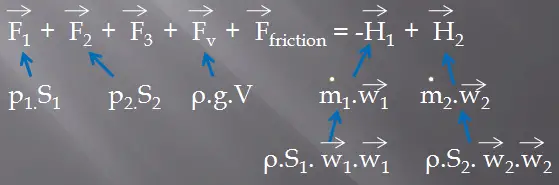

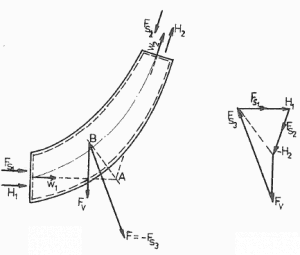

As can be seen from the picture, the control volume method can analyze the law of conservation of momentum in the fluid. The control volume is an imaginary surface enclosing a volume of interest. The control volume can be fixed or moving, and it can be rigid or deformable. To determine all forces acting on the surfaces of the control volume, we have to solve the conservation laws in this control volume.

The first conservation equation we have to consider in the control volume is the continuity equation (the law of conservation of matter). In the simplest form, it is represented by the following equation:

∑ṁin = ∑ṁout

Sum of mass flow rates entering per unit time = Sum of mass flow rates leaving per unit time

The second conservation equation we have to consider in the control volume is the momentum formula.

Momentum Formula

In the simplest form, the momentum formula can be represented by the following equation:

Choosing a Control Volume

A control volume can be selected as any arbitrary volume through which fluid flows. This volume can be static, moving, and even deforming during flow. To solve any problem, we have to solve basic conservation laws in this volume. It is very important to know all relative flow velocities to the control surface. Therefore it is very important to define exactly the boundaries of the control volume during an analysis.