Solutions of the Diffusion Equation – Multiplying Systems

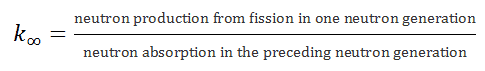

This condition can be expressed conveniently in terms of the multiplication factor. The infinite multiplication factor is the ratio of the neutrons produced by fission in one neutron generation to the number of neutrons lost through absorption in the preceding neutron generation. This can be mathematically expressed as shown below.

The infinite multiplication factor in a multiplying system measures the change in the fission neutron population from one neutron generation to the subsequent generation.

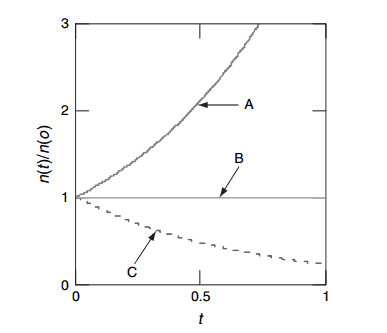

- k∞ < 1. Suppose the multiplication factor for a multiplying system is less than 1.0. In that case, the number of neutrons decreases in time (with the mean generation time), and the chain reaction will never be self-sustaining. This condition is known as the subcritical state.

- k∞ = 1. If the multiplication factor for a multiplying system is equal to 1.0, then there is no change in neutron population in time, and the chain reaction will be self-sustaining. This condition is known as the critical state.

- k∞ > 1. If the multiplication factor for a multiplying system is greater than 1.0, then the multiplying system produces more neutrons than are needed to be self-sustaining. The number of neutrons is exponentially increasing in time (with the mean generation time). This condition is known as the supercritical state.

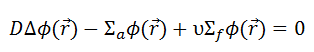

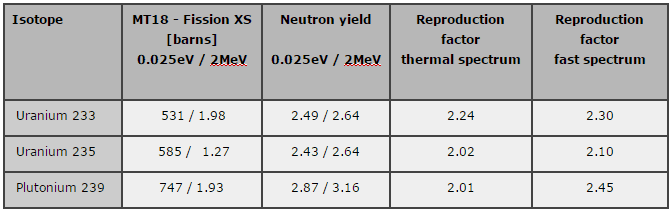

in various geometries that satisfy the boundary conditions. In this equation ν is number of neutrons emitted in fission and Σf is macroscopic cross-section of fission reaction. Ф denotes a reaction rate. For example a fission of 235U by thermal neutron yields 2.43 neutrons.

It must be noted that we will solve the diffusion equation without any external source. This is very important because such an equation is a linear homogeneous equation in the flux. Therefore if we find one solution of the equation, then any multiple is also a solution. This means that the absolute value of the neutron flux cannot possibly be deduced from the diffusion equation. This is different from problems with external sources, which determine the absolute value of the neutron flux.

We will start with simple systems (planar) and increase complexity gradually. The most important assumption is that all neutrons are lumped into a single energy group, they are emitted and diffuse at thermal energy (0.025 eV). Solutions of diffusion equations in this case provides an illustrative insights, how can be the neutron flux distributed in a reactor core.

Source: JANIS (Java-based nuclear information software)

http://www.oecd-nea.org/janis/

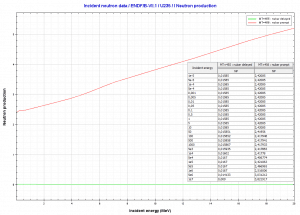

It is known the fission neutrons are of importance in any chain-reacting system. Neutrons trigger the nuclear fission of some nuclei (235U, 238U, or even 232Th). What is crucial the fission of such nuclei produces 2, 3, or more free neutrons.

But not all neutrons are released at the same time following fission. Even the nature of the creation of these neutrons is different. From this point of view, we usually divide the fission neutrons into two following groups:

- Prompt Neutrons. Prompt neutrons are emitted directly from fission, and they are emitted within a very short time of about 10-14 seconds.

- Delayed Neutrons. Delayed neutrons are emitted by neutron-rich fission fragments that are called delayed neutron precursors. These precursors usually undergo beta decay, but a small fraction of them are excited enough to undergo neutron emission. The neutron is produced via this type of decay, and this happens orders of magnitude later than the emission of the prompt neutrons, which plays an extremely important role in the control of the reactor.

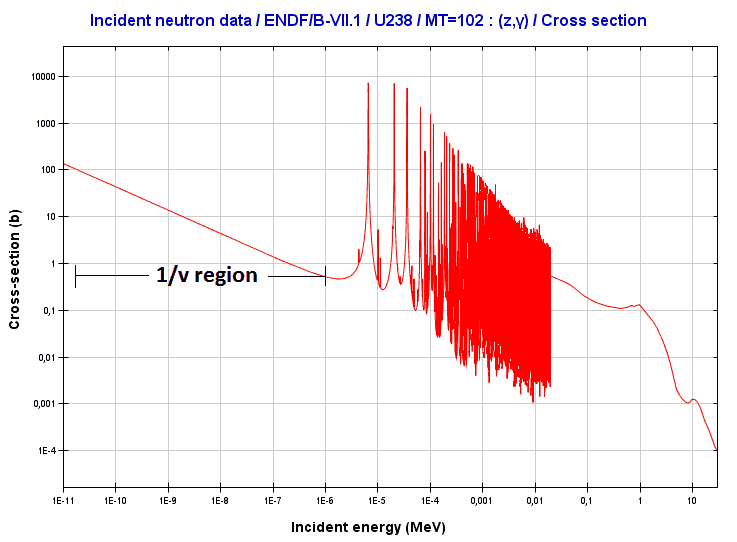

The most important absorption reactions are divided by the exit channel into two following reactions:

- Radiative Capture. Most absorption reactions result in the loss of a neutron coupled with the production of one or more gamma rays. This is referred to as a capture reaction, and it is denoted by σγ.

- Neutron-induced Fission Reaction. Some nuclei (fissionable nuclei) may undergo a fission event, leading to two or more fission fragments (nuclei of intermediate atomic weight) and a few neutrons. In a fissionable material, the neutron may simply be captured, or it may cause nuclear fission. For fissionable materials, we thus divide the absorption cross-section as σa = σγ+ σf.

Source: JANIS 4.0

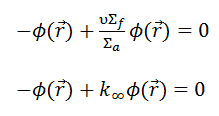

Since the neutron current is equal to zero (J = -D∇Ф, where Ф is constant), the diffusion equation in the infinite uniform multiplying system must be:

The only solution of this equation is a trivial solution, i.e., Ф = 0, unless Σa = νΣf. This equation (Σa = νΣf) is known as the criticality condition for an infinite reactor and expresses the perfect balance (critical state) between neutron absorption and neutron production. This balance must be continuously maintained to have a steady-state neutron flux.

Infinite Multiplication Factor

In this section, the infinite multiplication factor, k∞, will be defined from another point of view than in section – Nuclear Chain Reaction.

As can be seen, we can rewrite the diffusion equation in the following way, and we can define a new factor – k∞ = νΣf / Σa:

A non-trivial solution of this equation is guaranteed when k∞ = νΣf / Σa = 1. On the other hand, we have no information about the neutron flux in such a critical reactor. The neutron flux can have any value, and the critical uniform infinite reactor can operate at any power level. It should be noted this theory can be used for a reactor at low power levels, hence “zero power criticality”.

In a power reactor core, the power level does not influence the criticality of a reactor unless thermal reactivity feedbacks act (operation of a power reactor without reactivity feedbacks is between 10E-8% – 1% of rated power).

See also: Reactor Criticality

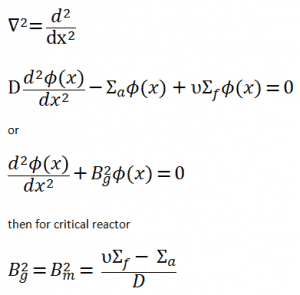

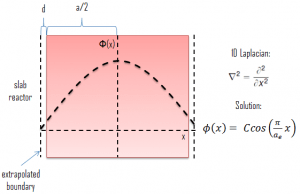

Let assume a uniform reactor (multiplying system) in the shape of a slab of physical width a in the x-direction and infinite in the y- and z-directions. This reactor is situated in the center at x=0. In this geometry, the flux does not vary in y and z allowing us to eliminate the y and z derivatives from ∇2. The flux is then a function of x only, and therefore the Laplacian and diffusion equation can be written as:

Let assume a uniform reactor (multiplying system) in the shape of a slab of physical width a in the x-direction and infinite in the y- and z-directions. This reactor is situated in the center at x=0. In this geometry, the flux does not vary in y and z allowing us to eliminate the y and z derivatives from ∇2. The flux is then a function of x only, and therefore the Laplacian and diffusion equation can be written as:

The quantity Bg2 is called the geometrical buckling of the reactor and depends only on the geometry. This term is derived from the notion that the neutron flux distribution is somehow “buckled” in a homogeneous finite reactor. It can be derived the geometrical buckling is the negative relative curvature of the neutron flux (Bg2 = ∇2Ф(x) / Ф(x)). The neutron flux has more concave downward or “buckled” curvature (higher Bg2) in a small reactor than in a large one. This is a very important parameter, and it will be discussed in the following sections.

For x > 0, this diffusion equation has two possible solutions sin(Bgx) and cos(Bgx), which give a general solution:

Φ(x) = A.sin(Bgx) + C.cos(Bg x)

From finite flux condition (0≤ Φ(x) < ∞), which required only reasonable values for the flux, it can be derived that A must be equal to zero. The term sin(Bgx) goes to negative values as x goes to negative values, and therefore it cannot be part of a physically acceptable solution. The physically acceptable solution must then be:

Φ(x) = C.cos(Bg x)

where Bg can be determined from the vacuum boundary condition.

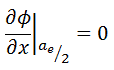

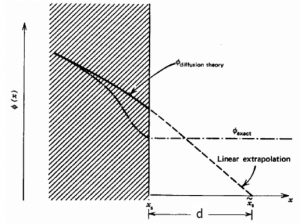

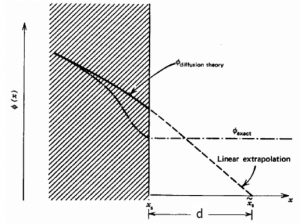

The vacuum boundary condition requires the relative neutron flux near the boundary to have a slope of -1/d, i.e., the flux would extrapolate linearly to 0 at a distance d beyond the boundary. This zero flux boundary condition is more straightforward and can be written mathematically as:

If d is not negligible, physical dimensions of the reactor are increased by d, and an extrapolated boundary is formulated with dimension ae/2 = a/2 + d. This condition can be written as Φ(a/2 + d) = Φ(ae/2) = 0.

Therefore, the solution must be Φ(ae/2) = C.cos(Bg .ae/2) = 0 and the values of geometrical buckling, Bg, are limited to Bg = nπ/a_e, where n is any odd integer. The only one physically acceptable odd integer is n=1 because higher values of n would give cosine functions which would become negative for some values of x. The solution of the diffusion equation is:

It must be added the constant C cannot be obtained from this diffusion equation because this constant gives the absolute value of neutron flux. The neutron flux can have any value, and the critical reactor can operate at any power level. It should be noted the cosine flux shape is only in a hypothetical case in a uniform homogeneous reactor at low power levels (at “zero power criticality”).

In the power reactor core (at full power operation), the neutron flux can reach, for example, about 3.11 x 1013 neutrons.cm-2.s-1, but this value depends significantly on many parameters (type of fuel, fuel burnup, fuel enrichment, position in fuel pattern, etc.).

The power level does not influence the criticality (keff) of a power reactor unless thermal reactivity feedbacks act (operation of a power reactor without reactivity feedbacks is between 10E-8% – 1% of rated power).

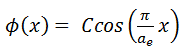

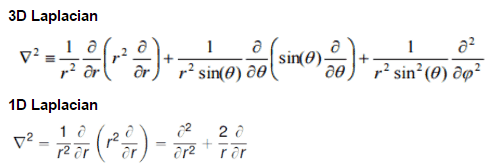

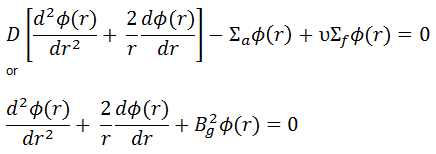

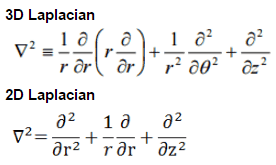

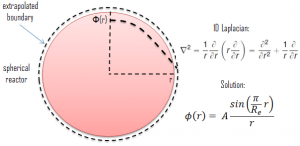

Let us assume a uniform reactor (multiplying system) in the shape of a sphere of physical radius R. The spherical reactor is situated in spherical geometry at the origin of coordinates. To solve the diffusion equation, we have to replace the Laplacian with its spherical form:

Let us assume a uniform reactor (multiplying system) in the shape of a sphere of physical radius R. The spherical reactor is situated in spherical geometry at the origin of coordinates. To solve the diffusion equation, we have to replace the Laplacian with its spherical form:

We can replace the 3D Laplacian with its one-dimensional spherical form because there is no dependence on an angle (whether polar or azimuthal). The source term is assumed to be isotropic (there is the spherical symmetry). The flux is then a function of radius – r only, and therefore the diffusion equation can be written as:

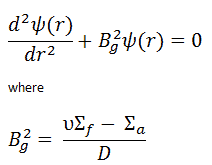

The solution of the diffusion equation is based on a substitution Φ(r) = 1/r ψ(r), that leads to an equation for ψ(r):

For r > 0, this differential equation has two possible solutions, sin(Bgr) and cos(Bgr), which give a general solution:

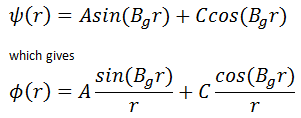

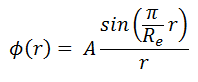

From finite flux condition (0≤ Φ(r) < ∞), which required only reasonable values for the flux, it can be derived that C must be equal to zero. The term cos(Bgr)/r goes to ∞ as r ➝0 and therefore cannot be part of a physically acceptable solution. The physically acceptable solution must then be:

Φ(r) = A sin(Bgr)/r

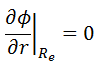

The vacuum boundary condition requires the relative neutron flux near the boundary to have a slope of -1/d, i.e., the flux would extrapolate linearly to 0 at a distance d beyond the boundary. This zero flux boundary condition is more straightforward and can be written mathematically as:

If d is not negligible, physical dimensions of the reactor are increased by d, and extrapolated boundary is formulated with dimension Re = R + d, and this condition can be written as Φ(R + d) = Φ(Re) = 0.

Therefore, the solution must be Φ(Re) = A sin(BgRe)/Re = 0, and the values of geometrical buckling, Bg, are limited to Bg = nπ/Re, where n is any odd integer. The only one physically acceptable odd integer is n=1 because higher values of n would give sine functions which would become negative for some values of x before returning to 0 at Re. The solution of the diffusion equation is:

It must be added the constant A cannot be obtained from this diffusion equation because this constant gives the absolute value of neutron flux. The neutron flux can have any value, and the critical reactor can operate at any power level. It should be noted this flux shape is only in a hypothetical case in a uniform homogeneous spherical reactor at low power levels (at “zero power criticality”).

In a power reactor core, the neutron flux can reach, for example, about 3.11 x 1013 neutrons.cm-2.s-1, but this value depends significantly on many parameters (type of fuel, fuel burnup, fuel enrichment, position in fuel pattern, etc.).

The power level does not influence the criticality (keff) of a power reactor unless thermal reactivity feedbacks act (operation of a power reactor without reactivity feedbacks is between 10E-8% – 1% of rated power).

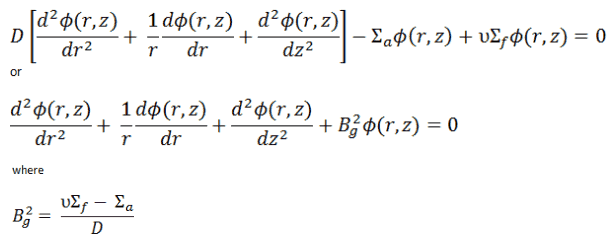

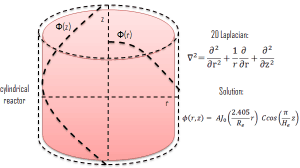

Let assume a uniform reactor (multiplying system) in the shape of a cylinder of physical radius R and height H. This finite cylindrical reactor is situated in cylindrical geometry at the origin of coordinates. To solve the diffusion equation, we have to replace the Laplacian by its cylindrical form:

Let assume a uniform reactor (multiplying system) in the shape of a cylinder of physical radius R and height H. This finite cylindrical reactor is situated in cylindrical geometry at the origin of coordinates. To solve the diffusion equation, we have to replace the Laplacian by its cylindrical form:

Since there is no dependence on angle Θ, we can replace the 3D Laplacian with its two-dimensional form and solve the problem in radial and axial directions. Since the flux is a function of radius – r and height – z only (Φ(r,z)), the diffusion equation can be written as:

The solution of this diffusion equation is based on the use of the separation-of-variables technique, therefore:

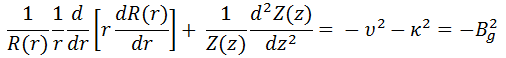

where R(r) and Z(z) are functions to be determined. Substituting this into the diffusion equation and dividing by R(r)Z(z), we obtain:

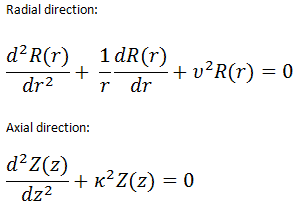

Because the first term depends only on r and the second only on z, both terms must be constants for the equation to have a solution. Suppose we take the constants to be v2 and к2. The sum of these constants must be equal to Bg2 = v2 + к2. Now we can separate variables, and the neutron flux must satisfy the following differential equations:

Solution for the radial direction

The differential equation for radial direction is called Bessel’s equation, and it is well known to mathematicians. In this case, the Bessel’s equation’s solutions are called the Bessel functions of the first and second kind, Jα(x) and Yα(x), respectively.

The differential equation for radial direction is called Bessel’s equation, and it is well known to mathematicians. In this case, the Bessel’s equation’s solutions are called the Bessel functions of the first and second kind, Jα(x) and Yα(x), respectively.

For r > 0, this differential equation has two possible solutions, J0(vr) and Y0(vr), the Bessel functions of order zero, which give a general solution:

From finite flux condition (0≤ Φ(r) < ∞), which required only reasonable values for the flux, it can be derived that C must be equal to zero. The term Y0(vr) goes to -∞ as r ➝0 and therefore cannot be part of a physically acceptable solution. The physically acceptable solution must then be:

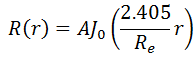

R(r) = AJ0(vr)

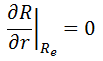

The vacuum boundary condition requires the relative neutron flux near the boundary to have a slope of -1/d, i.e., the flux would extrapolate linearly to 0 at a distance d beyond the boundary. This zero flux boundary condition is more straightforward, and it can be written mathematically as:

If d is not negligible, physical dimensions of the reactor are increased by d, and extrapolated boundary is formulated with dimension Re = R + d, and this condition can be written as Φ(R + d) = Φ(Re) = 0.

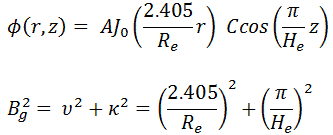

Therefore, the solution must be R(Re) = A J0(vRe) = 0. The function of J0(r) has several zeroes. The first is at r1 = 2.405, and the second at r2 = 5.6. However, because the neutron flux cannot have regions of negative values, the only physically acceptable value for v is 2.405/Re. The solution of the diffusion equation is:

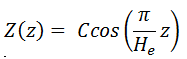

Solution for axial direction

The solution for axial direction has been solved in previous sections (Infinite Slab Reactor), and therefore it has the same solution. The solution in an axial direction is:

Solution for radial and axial directions

The full solution for the neutron flux distribution in the finite cylindrical reactor is, therefore:

where Bg2 is the total geometrical buckling.

The constants A and C must be added that they cannot be obtained from the diffusion equation because they give the absolute value of neutron flux. The neutron flux can have any value, and the critical reactor can operate at any power level. It should be noted this flux shape is only in a hypothetical case in a uniform homogeneous cylindrical reactor at low power levels (at “zero power criticality”).

In a power reactor core, the neutron flux can reach, for example, about 3.11 x 1013 neutrons.cm-2.s-1, but this value depends significantly on many parameters (type of fuel, fuel burnup, fuel enrichment, position in fuel pattern, etc.).

The power level does not influence the criticality (keff) of a power reactor unless thermal reactivity feedbacks act (operation of a power reactor without reactivity feedbacks is between 10E-8% – 1% of rated power).

- J. R. Lamarsh, Introduction to Nuclear Reactor Theory, 2nd ed., Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA (1983).

- J. R. Lamarsh, A. J. Baratta, Introduction to Nuclear Engineering, 3d ed., Prentice-Hall, 2001, ISBN: 0-201-82498-1.

- W. M. Stacey, Nuclear Reactor Physics, John Wiley & Sons, 2001, ISBN: 0- 471-39127-1.

- Glasstone, Sesonske. Nuclear Reactor Engineering: Reactor Systems Engineering, Springer; 4th edition, 1994, ISBN: 978-0412985317

- W.S.C. Williams. Nuclear and Particle Physics. Clarendon Press; 1 edition, 1991, ISBN: 978-0198520467

- G.R.Keepin. Physics of Nuclear Kinetics. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co; 1st edition, 1965

- Robert Reed Burn, Introduction to Nuclear Reactor Operation, 1988.

- U.S. Department of Energy, Nuclear Physics and Reactor Theory. DOE Fundamentals Handbook, Volume 1 and 2. January 1993.

Advanced Reactor Physics:

- K. O. Ott, W. A. Bezella, Introductory Nuclear Reactor Statics, American Nuclear Society, Revised edition (1989), 1989, ISBN: 0-894-48033-2.

- K. O. Ott, R. J. Neuhold, Introductory Nuclear Reactor Dynamics, American Nuclear Society, 1985, ISBN: 0-894-48029-4.

- D. L. Hetrick, Dynamics of Nuclear Reactors, American Nuclear Society, 1993, ISBN: 0-894-48453-2.

- E. E. Lewis, W. F. Miller, Computational Methods of Neutron Transport, American Nuclear Society, 1993, ISBN: 0-894-48452-4.