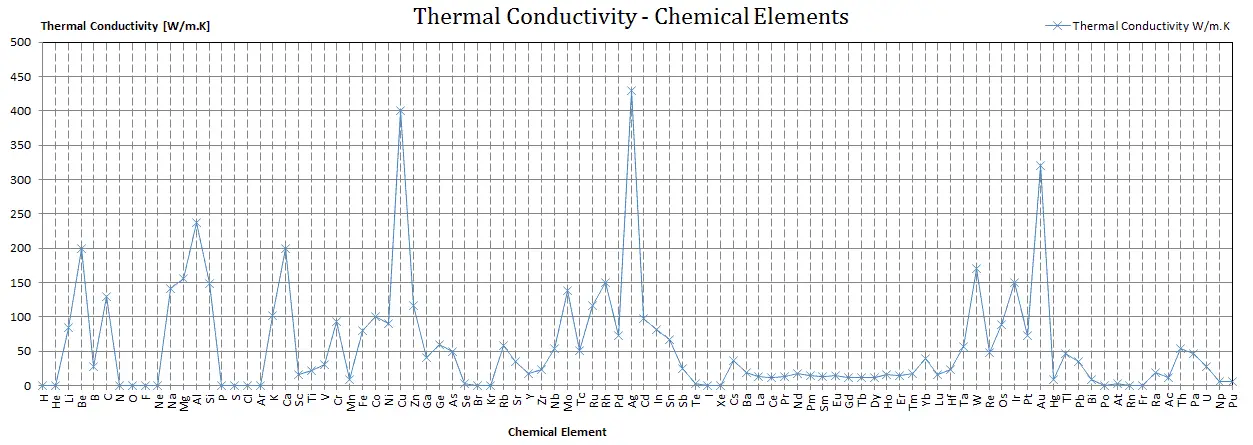

Metals, in general, have high electrical conductivity high thermal conductivity. The thermal conductivities of metals originate from the fact that their outer electrons are delocalized.

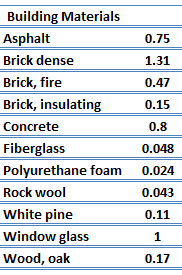

Thermal insulators have very low thermal conductivity. Their low thermal conductivity is based on the alternation of gas pocket and solid material that causes the heat must be transferred through many interfaces causing a rapid decrease in heat transfer coefficient.

The thermal conductivity of most liquids and solids varies with temperature, and for vapors, it also depends upon pressure. In general:

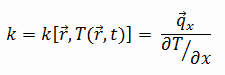

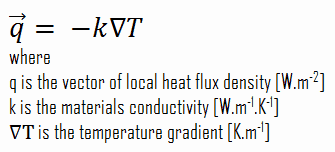

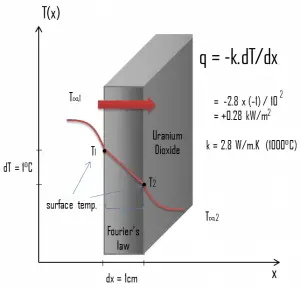

Most materials are very nearly homogeneous. Therefore, we can usually write k = k (T). Similar definitions are associated with thermal conductivities in the y- and z-directions (ky, kz), but for an isotropic material, the thermal conductivity is independent of the direction of transfer, kx = ky = kz = k. Note that Fourier’s law applies to all matter, regardless of its state (solid, liquid, or gas). Therefore, it is also defined for liquids and gases.

Most materials are very nearly homogeneous. Therefore, we can usually write k = k (T). Similar definitions are associated with thermal conductivities in the y- and z-directions (ky, kz), but for an isotropic material, the thermal conductivity is independent of the direction of transfer, kx = ky = kz = k. Note that Fourier’s law applies to all matter, regardless of its state (solid, liquid, or gas). Therefore, it is also defined for liquids and gases.

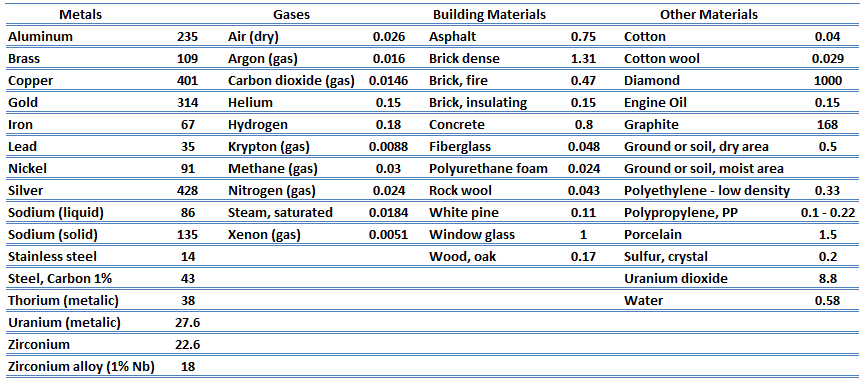

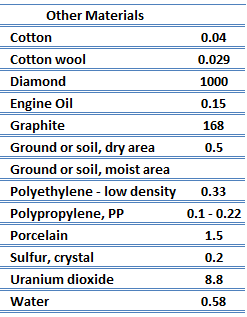

The previous equation follows that the conduction heat flux increases with increasing thermal conductivity and increases with increasing temperature differences. In general, the thermal conductivity of a solid is larger than that of a liquid, which is larger than that of a gas. This trend is due largely to differences in intermolecular spacing for the two states of matter. In particular, diamond has the highest hardness and thermal conductivity of any bulk material.

See also: Thermal Conductivity of Common Materials

Thermal Conductivity of Fluids (Liquids and Gases)

In physics, a fluid is a substance that continually deforms (flows) under applied shear stress. Fluids are a subset of the phases of matter and include liquids, gases, plasmas, and, to some extent, plastic solids. Because the intermolecular spacing is much larger and the motion of the molecules is more random for the fluid state than for the solid-state, thermal energy transport is less effective. The thermal conductivity of gases and liquids is generally smaller than that of solids. In liquids, thermal conduction is caused by atomic or molecular diffusion. In gases, thermal conduction is caused by the diffusion of molecules from a higher energy level to a lower level.

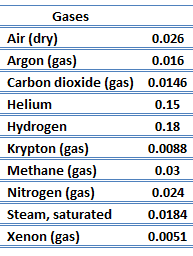

Thermal Conductivity of Gases

The effect of temperature, pressure and chemical species on the thermal conductivity of a gas may be explained in terms of the kinetic theory of gases. Air and other gases are generally good insulators in the absence of convection. Therefore, many insulating materials (e.g., polystyrene) function simply by having a large number of gas-filled pockets, which prevent large-scale convection. Alternation of gas pocket and solid material causes heat to transfer through many interfaces, causing a rapid decrease in heat transfer coefficient.

The effect of temperature, pressure and chemical species on the thermal conductivity of a gas may be explained in terms of the kinetic theory of gases. Air and other gases are generally good insulators in the absence of convection. Therefore, many insulating materials (e.g., polystyrene) function simply by having a large number of gas-filled pockets, which prevent large-scale convection. Alternation of gas pocket and solid material causes heat to transfer through many interfaces, causing a rapid decrease in heat transfer coefficient.

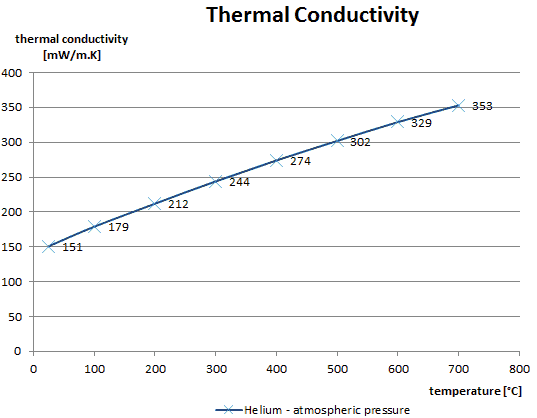

The thermal conductivity of gases is directly proportional to the density of the gas, the mean molecular speed, and especially to the mean free path of a molecule. The mean free path also depends on the diameter of the molecule, with larger molecules more likely to experience collisions than small molecules, which is the average distance traveled by an energy carrier (a molecule) before experiencing a collision. Light gases, such as hydrogen and helium, typically have high thermal conductivity, and dense gases such as xenon and dichlorodifluoromethane have low thermal conductivity.

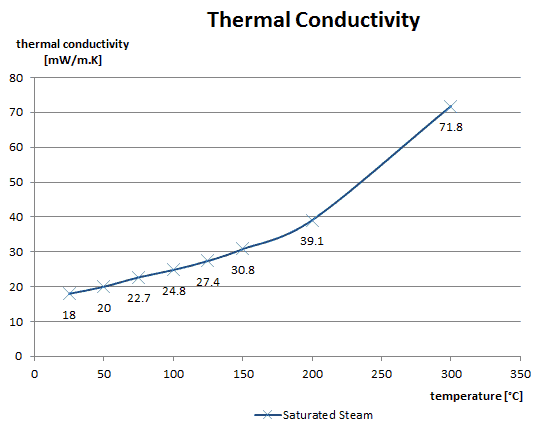

In general, the thermal conductivity of gases increases with increasing temperature.

Thermal Conductivity of Liquids

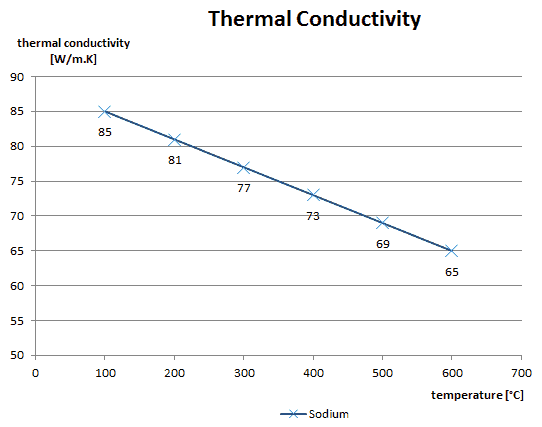

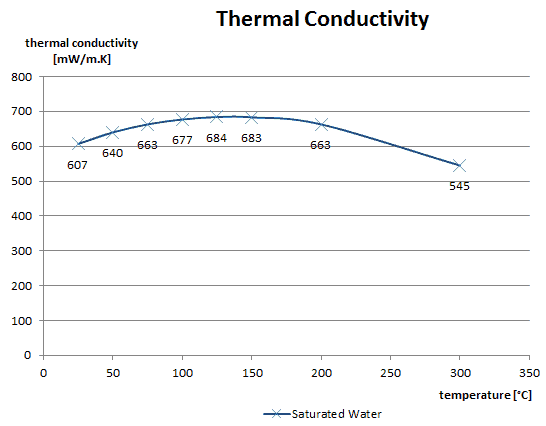

As was written, in liquids, the thermal conduction is caused by atomic or molecular diffusion, but physical mechanisms for explaining the thermal conductivity of liquids are not well understood. Liquids tend to have better thermal conductivity than gases, and the ability to flow makes a liquid suitable for removing excess heat from mechanical components. The heat can be removed by channeling the liquid through a heat exchanger. The coolants used in nuclear reactors include water or liquid metals, such as sodium or lead.

The thermal conductivity of nonmetallic liquids generally decreases with increasing temperature.

Thermal Conductivity of Solids

Transport of thermal energy in solids may generally be due to two effects:

- the migration of free electrons

- lattice vibrational waves (phonons)

When electrons and phonons carry thermal energy leading to conduction heat transfer in a solid, the thermal conductivity may be expressed as:

k = ke + kph

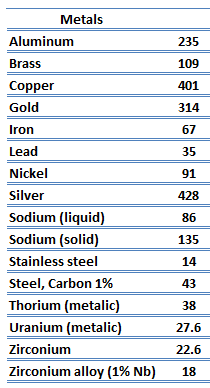

Thermal Conductivity of Metals

Metals are solids, and as such, they possess a crystalline structure where the ions (nuclei with their surrounding shells of core electrons) occupy translationally equivalent positions in the crystal lattice. Metals, in general, have high electrical conductivity, high thermal conductivity, and high density. Accordingly, transport of thermal energy may be due to two effects:

Metals are solids, and as such, they possess a crystalline structure where the ions (nuclei with their surrounding shells of core electrons) occupy translationally equivalent positions in the crystal lattice. Metals, in general, have high electrical conductivity, high thermal conductivity, and high density. Accordingly, transport of thermal energy may be due to two effects:

- the migration of free electrons

- lattice vibrational waves (phonons).

When electrons and phonons carry thermal energy leading to conduction heat transfer in a solid, the thermal conductivity may be expressed as:

k = ke + kph

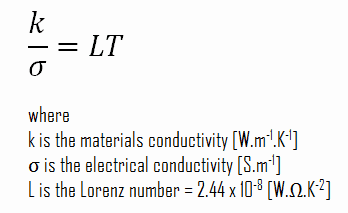

As far as their structure is concerned, the unique feature of metals is the presence of charge carriers, specifically electrons. The electrical and thermal conductivities of metals originate from the fact that their outer electrons are delocalized. Their contribution to the thermal conductivity is referred to as the electronic thermal conductivity, ke. In fact, in pure metals such as gold, silver, copper, and aluminum, the heat current associated with the flow of electrons by far exceeds a small contribution due to the flow of phonons. In contrast, for alloys, the contribution of kph to k is no longer negligible.

Thermal Conductivity of Nonmetals

For nonmetallic solids, k is determined primarily by kph, which increases as the frequency of interactions between the atoms and the lattice decreases. Lattice thermal conduction is the dominant thermal conduction mechanism in nonmetals, if not the only one. In solids, atoms vibrate about their equilibrium positions (crystal lattice). The vibrations of atoms are not independent of each other but are rather strongly coupled with neighboring atoms. The regularity of the lattice arrangement has an important effect on kph, with crystalline (well-ordered) materials like quartz having a higher thermal conductivity than amorphous materials like glass, at sufficiently high temperatures kph ∝ 1/T.

For nonmetallic solids, k is determined primarily by kph, which increases as the frequency of interactions between the atoms and the lattice decreases. Lattice thermal conduction is the dominant thermal conduction mechanism in nonmetals, if not the only one. In solids, atoms vibrate about their equilibrium positions (crystal lattice). The vibrations of atoms are not independent of each other but are rather strongly coupled with neighboring atoms. The regularity of the lattice arrangement has an important effect on kph, with crystalline (well-ordered) materials like quartz having a higher thermal conductivity than amorphous materials like glass, at sufficiently high temperatures kph ∝ 1/T.

The quanta of the crystal vibrational field are referred to as “phonons.” A phonon is a collective excitation in a periodic, elastic arrangement of atoms or molecules in condensed matter, like solids and some liquids. Phonons play a major role in many of the physical properties of condensed matter, like thermal conductivity and electrical conductivity. In fact, for crystalline, nonmetallic solids such as diamond kph can be quite large, exceeding values of k associated with good conductors, such as aluminum. In particular, diamond has the highest hardness and thermal conductivity (k = 1000 W/m.K) of any bulk material.

The quanta of the crystal vibrational field are referred to as “phonons.” A phonon is a collective excitation in a periodic, elastic arrangement of atoms or molecules in condensed matter, like solids and some liquids. Phonons play a major role in many of the physical properties of condensed matter, like thermal conductivity and electrical conductivity. In fact, for crystalline, nonmetallic solids such as diamond kph can be quite large, exceeding values of k associated with good conductors, such as aluminum. In particular, diamond has the highest hardness and thermal conductivity (k = 1000 W/m.K) of any bulk material.

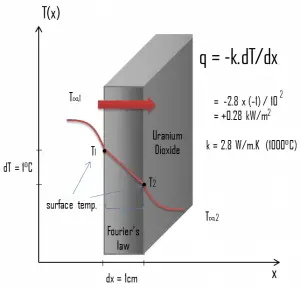

Thermal Conductivity of Uranium Dioxide

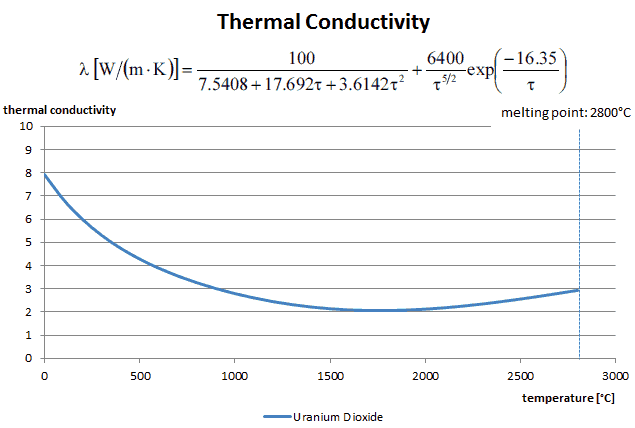

Most PWRs use uranium fuel, which is in the form of uranium dioxide. Uranium dioxide is a black semiconducting solid with very low thermal conductivity. On the other hand, uranium dioxide has a very high melting point and well-known behavior. The UO2 is pressed into pellets, and these pellets are then sintered into the solid.

Most PWRs use uranium fuel, which is in the form of uranium dioxide. Uranium dioxide is a black semiconducting solid with very low thermal conductivity. On the other hand, uranium dioxide has a very high melting point and well-known behavior. The UO2 is pressed into pellets, and these pellets are then sintered into the solid.

These pellets are then loaded and encapsulated within a fuel rod (or fuel pin) made of zirconium alloys due to their very low absorption cross-section (unlike stainless steel). The surface of the tube, which covers the pellets, is called fuel cladding. Fuel rods are the base element of a fuel assembly.

The thermal conductivity of uranium dioxide is very low compared with metal uranium, uranium nitride, uranium carbide, and zirconium cladding material. Thermal conductivity is one of the parameters which determine the fuel centerline temperature. This low thermal conductivity can result in localized overheating in the fuel centerline, and therefore this overheating must be avoided. Overheating of the fuel is prevented by maintaining the steady-state peak linear heat rate (LHR) or the Heat Flux Hot Channel Factor – FQ(z) below the level at which fuel centerline melting occurs. Expansion of the fuel pellet upon centerline melting may cause the pellet to stress the cladding to the point of failure.

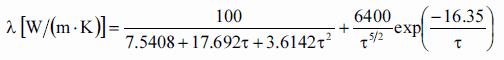

Thermal conductivity of solid UO2 with a density of 95% is estimated by the following correlation [Klimenko; Zorin]:

where τ = T/1000. The uncertainty of this correlation is +10% in the range from 298.15 to 2000 K and +20% in the range from 2000 to 3120 K.

Special reference: Thermal and Nuclear Power Plants/Handbook ed. by A.V. Klimenko and V.M. Zorin. MEI Press, 2003.

Special reference: Thermophysical Properties of Materials For Nuclear Engineering: A Tutorial and Collection of Data. IAEA-THPH, IAEA, Vienna, 2008. ISBN 978–92–0–106508–7.

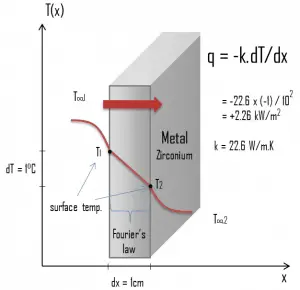

Thermal Conductivity of Zirconium

Zirconium is a lustrous, grey-white, strong transition metal that resembles hafnium and titanium to a lesser extent. Zirconium is mainly used as a refractory and opacifier, although small amounts are used as an alloying agent for strong corrosion resistance. Zirconium alloy (e.g., Zr + 1%Nb) is widely used as a cladding for nuclear reactor fuels. The desired properties of these alloys are a low neutron-capture cross-section and resistance to corrosion under normal service conditions. Zirconium alloys have lower thermal conductivity (about 18 W/m.K) than pure zirconium metal (about 22 W/m.K).

Zirconium is a lustrous, grey-white, strong transition metal that resembles hafnium and titanium to a lesser extent. Zirconium is mainly used as a refractory and opacifier, although small amounts are used as an alloying agent for strong corrosion resistance. Zirconium alloy (e.g., Zr + 1%Nb) is widely used as a cladding for nuclear reactor fuels. The desired properties of these alloys are a low neutron-capture cross-section and resistance to corrosion under normal service conditions. Zirconium alloys have lower thermal conductivity (about 18 W/m.K) than pure zirconium metal (about 22 W/m.K).

Special reference: Thermophysical Properties of Materials For Nuclear Engineering: A Tutorial and Collection of Data. IAEA-THPH, IAEA, Vienna, 2008. ISBN 978–92–0–106508–7.