In general, convection is either the mass transfer or the heat transfer due to the bulk movement of molecules within fluids such as gases and liquids. Although liquids and gases are generally not very good conductors of heat, they can transfer heat quite rapidly by convection. Convection takes place through advection, diffusion, or both. In preceding chapters, we considered convection transfer in fluid flows originating from an external forcing condition – forced convection. This chapter considers natural convection, where any fluid motion occurs by natural means such as buoyancy.

Definition of Natural Convection

Natural convection, also known as free convection, is a mechanism, or type of mass and heat transport, in which the fluid motion is generated only by density differences in the fluid occurring due to temperature gradients, not by any external source (like a pump, fan, suction device, etc.).

Natural convection, also known as free convection, is a mechanism, or type of mass and heat transport, in which the fluid motion is generated only by density differences in the fluid occurring due to temperature gradients, not by any external source (like a pump, fan, suction device, etc.).

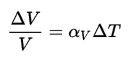

In natural convection, fluid surrounding a heat source receives heat, becomes less dense, and rises by thermal expansion. Thermal expansion of the fluid plays a crucial role. In other words, heavier (more dense) components will fall, while lighter (less dense) components rise, leading to bulk fluid movement. Natural convection can only occur in a gravitational field or the presence of another proper acceleration, such as:

- acceleration

- centrifugal force

- Coriolis force

Natural convection essentially does not operate in the orbit of Earth. For example, in the orbiting International Space Station, other heat transfer mechanisms are required to prevent electronic components from overheating.

See also: Natural Circulation

Natural Convection – Heat Transfer

Similarly, as for forced convection, natural convection heat transfer takes place both by thermal diffusion (the random motion of fluid molecules) and by advection, in which matter or heat is transported by the larger-scale motion of currents in the fluid. Energy flow occurs purely by conduction at the surface, even in convection. It is because there is always a thin stagnant fluid film layer on the heat transfer surface. But in the next layers, both conduction and diffusion-mass movement occur at the molecular or macroscopic levels. Due to the mass movement, the rate of energy transfer is higher. The higher the mass movement rate, the thinner the stagnant fluid film layer will be, and the higher the heat flow rate.

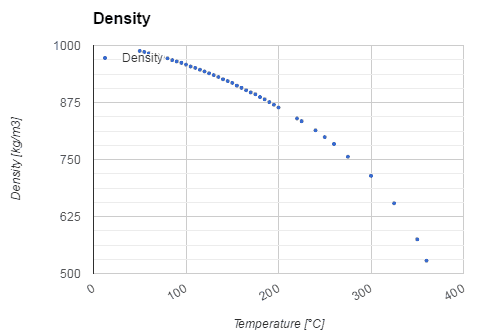

We know that the density of gases and liquids depends on temperature, generally decreasing (due to fluid expansion) with increasing temperature.

We know that the density of gases and liquids depends on temperature, generally decreasing (due to fluid expansion) with increasing temperature.

The magnitude of the natural convection heat transfer between a surface and a fluid is directly related to the flow rate of the fluid induced by natural convection. The higher the flow rate, the higher the heat transfer rate. The flow rate in the case of natural convection is established by the dynamic balance of buoyancy and friction.

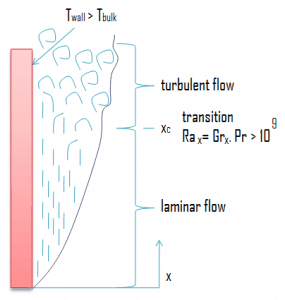

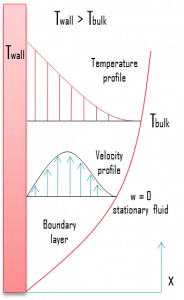

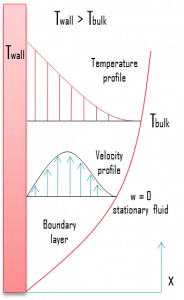

Assume a plate at the temperature Twall, which is immersed in a quiescent fluid at the temperature Tbulk, where (Twall > Tbulk). The fluid close to the plate is less dense than the fluid that is further removed. Buoyancy forces, therefore, induce a natural convection boundary layer in which the heated and lighter fluid rises vertically, entraining heavier fluid from the quiescent region. The resulting velocity distribution is unlike that of forced convection boundary layers and depends on the fluid viscosity. In particular, the velocity is zero at the surface as well as at the boundary due to viscous forces. It must be noted natural convection also develops if (Twall < Tbulk), but, in this case, a fluid motion will be downward.

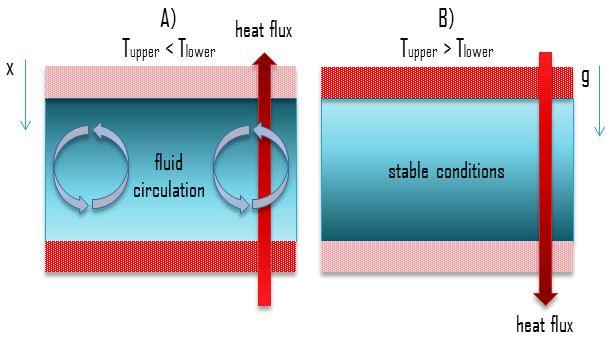

The presence and magnitude of natural convection also depend on the geometry of the problem. The presence of a fluid density gradient in a gravitational field does not ensure the existence of natural convection currents. This problem is illustrated in the following figure, where a fluid is enclosed by two large, horizontal plates of different temperatures (Tupper ≠ Tlower).

- In case A, the temperature of the lower plate is higher than the temperature of the upper plate. In this case, the density decreases in the direction of the gravitational force. This geometry induces fluid circulation, and heat transfer occurs via natural circulation. The heavier fluid will descend, being warmed in the process, while the lighter fluid will rise, cooling as it moves.

- In case B, the temperature of the lower plate is lower than the temperature of the upper plate. In this case, the density increases in the direction of the gravitational force. This geometry leads to stable conditions, stable temperature gradient and does not induce fluid circulation. Heat transfer occurs solely via thermal conduction.

Since natural convection is strongly dependent on geometry, most heat transfer correlations in natural convection are based on experimental measurements, and engineers often use proper characteristic numbers to describe natural convection heat transfer.

Natural Convection – Correlations

Most heat transfer correlations in natural convection are based on experimental measurements, and engineers often use proper characteristic numbers to describe natural convection heat transfer. The characteristic number that describes convective heat transfer (i.e., the heat transfer coefficient) is the Nusselt number, which is defined as the ratio of the thermal energy convected to the fluid to the thermal energy conducted within the fluid. The Nusselt number represents the enhancement of heat transfer through a fluid layer due to convection relative to conduction across the same fluid layer. But in the case of free convection, heat transfer correlations (for the Nusselt number) are usually expressed in terms of the Rayleigh number.

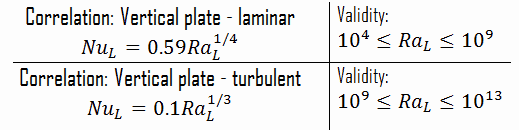

The Rayleigh number is used to express heat transfer in natural convection. The magnitude of the Rayleigh number is a good indication of whether the natural convection boundary layer is laminar or turbulent. The simple empirical correlations for the average Nusselt number, Nu, in natural convection are of the form:

Nux = C. Raxn

The constants C and n depend on the geometry of the surface and the flow regime, which is characterized by the range of the Rayleigh number. The value of n is usually n = 1/4 for laminar flow and n = 1/3 for turbulent flow.

For example:

See also: Nusselt Number

See also: Rayleigh Number

Example: Natural Convection – Flat Plate

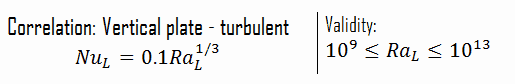

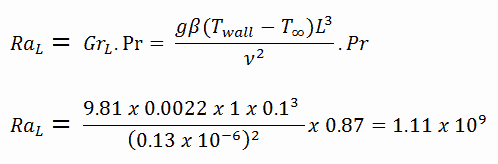

A 10cm high vertical plate is maintained at 261°C in 260°C compressed water (16MPa). Determine the Nusselt number using the simple correlation for a vertical flat plate.

To calculate the Rayleigh number, we have to know:

- the coefficient of thermal expansion, which is: β = 0.0022

- the Prandtl number (for 260°C), which is: Pr = 0.87

- the kinematic viscosity (for 260°C), which is ν = 0.13 x 10-6 (note that this value is significantly lower than that for 20°C)

The resulting Rayleigh number is:

The resulting Nusselt number, which represents the enhancement of heat transfer through a fluid layer as a result of convection relative to conduction across the same fluid layer, is:

Combined Forced and Natural Convection

As was written, convection takes place through advection, diffusion, or both. In preceding chapters, we considered convection transfer in fluid flows originating from an external forcing condition – forced convection. This chapter considers natural convection, where any fluid motion occurs by natural means such as buoyancy. There are flow regimes in which we have to consider both forcing mechanisms. When flow velocities are low, natural convection will also contribute in addition to forced convection. Whether or not free convection is significant for heat transfer can be checked using the following criteria:

As was written, convection takes place through advection, diffusion, or both. In preceding chapters, we considered convection transfer in fluid flows originating from an external forcing condition – forced convection. This chapter considers natural convection, where any fluid motion occurs by natural means such as buoyancy. There are flow regimes in which we have to consider both forcing mechanisms. When flow velocities are low, natural convection will also contribute in addition to forced convection. Whether or not free convection is significant for heat transfer can be checked using the following criteria:

- If Gr/Re2 >> 1 free convection prevails

- If Gr/Re2 << 1 forced convection prevails

- If Gr/Re2 ≈ 1 both should be considered

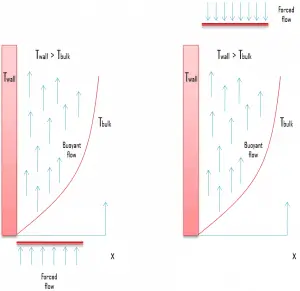

The effect of buoyancy on heat transfer in a forced flow is strongly influenced by the direction of the buoyancy force relative to that of the flow. Natural convection may help or hurt forced convection heat transfer, depending on the relative directions of buoyancy-induced and the forced convection motions. Three special cases that have been studied extensively correspond to buoyancy-induced and forced motions:

- Assisting flow. The buoyant motion is in the same direction as the forced motion.

- Opposing flow. The buoyant motion is in the opposite direction to the forced motion.

- Transverse flow. The buoyant motion is perpendicular to the forced motion.

Obviously, in assisting and transverse flows, buoyancy enhances the rate of heat transfer associated with pure forced convection. On the other hand, opposing flows decrease the rate of heat transfer. When determining the Nusselt number under combined natural and forced convection conditions, it is tempting to add the contributions of natural and forced convection in assisting flows and to subtract them in opposing flows:

The Nusselt numbers Nuforced and Nunatural are determined from existing correlations for pure forced and natural (free) convection for the specific geometry of interest. The best correlation of data to experiments is often obtained for exponent n = 3, but it may vary between 3 and 4, depending on the geometry of the problem.

Natural Circulation

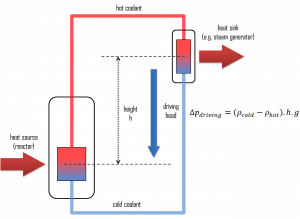

Natural circulation is the circulation of fluid within piping systems or open pools due to the density changes caused by temperature differences. Natural circulation does not require any mechanical devices to maintain flow.

This phenomenon has similar nature to natural convection, but in this case, the heat transfer coefficient is not an object of study. In this case, the bulk flow through the loop is the object of study. This phenomenon is rather a hydraulic problem than a heat transfer problem. However, as a result, natural circulation removes heat from the source and transports it to the heat sink and is of the highest importance in reactor safety.

See also: Natural Circulation