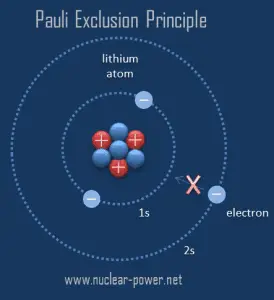

The Pauli exclusion principle is the principle formulated by Wolfgang Pauli in 1925, which states that:

In terms of the quantum numbers:

No two electrons in an atom can have the same values as all four quantum numbers.

Two electrons of a multielectron atom can’t have the same values as the four quantum numbers:

- n – the principal quantum number,

- ℓ – the angular momentum quantum number

- mℓ – the magnetic quantum number,

- ms – the spin quantum number.

Mathematically this means the wavefunctions of the two particles must be antisymmetric, which leads to the probability amplitude of the wavefunction going to zero if the two fermionic particles are the same.

The Pauli exclusion principle requires the electrons in an atom to occupy different energy levels instead of them all condensing in the ground state. The ordering of the electrons in the ground state of multielectron atoms starts with the lowest energy state (ground state). It moves progressively up the energy scale until each atom’s electrons have been assigned a unique set of quantum numbers. This fact has key implications for building up the periodic table of elements.

The Pauli exclusion principle requires the electrons in an atom to occupy different energy levels instead of them all condensing in the ground state. The ordering of the electrons in the ground state of multielectron atoms starts with the lowest energy state (ground state). It moves progressively up the energy scale until each atom’s electrons have been assigned a unique set of quantum numbers. This fact has key implications for building up the periodic table of elements.

It must be noted chemical properties of atoms are determined by the number of protons, in fact, by the number and arrangement of electrons. The configuration of these electrons follows the principles of quantum mechanics and the Pauli exclusion principle. The number of electrons in each element’s electron shells, particularly the outermost valence shell, is the primary factor determining its chemical bonding behavior. Without the Pauli exclusion principle, there would be no chemistry.

This principle must be considered for any particles whose spin quantum number s is not zero or an integer. Therefore, this principle applies not only to electrons but also to protons and neutrons, all of which have half-integer spin.

Pauli Exclusion Principle and Nuclear Stability

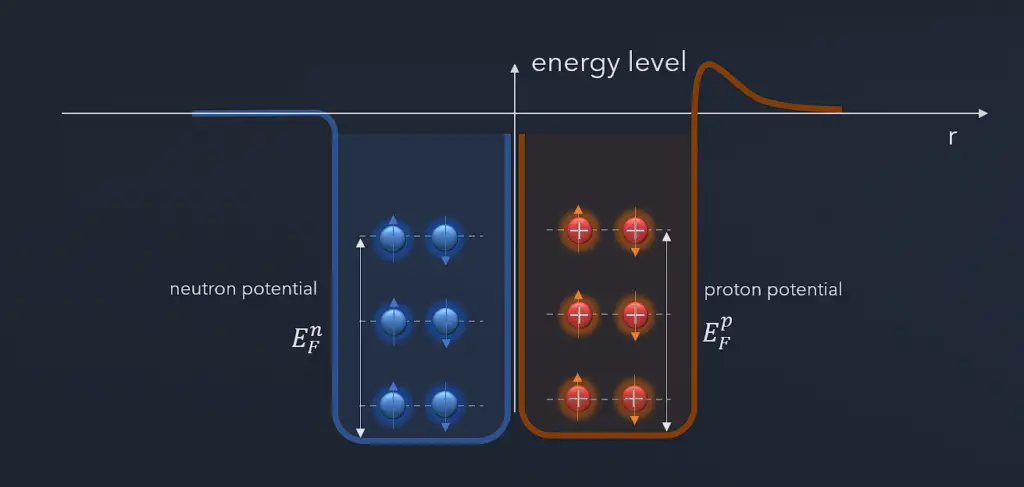

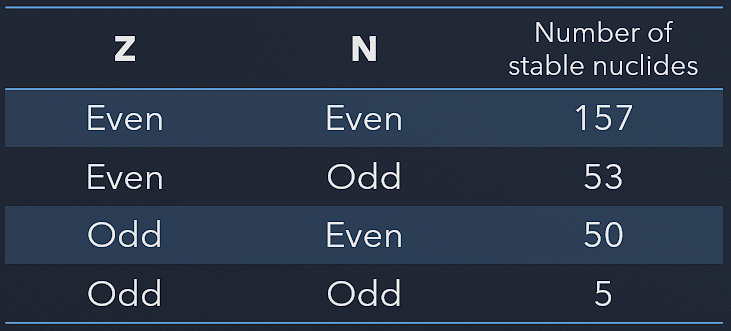

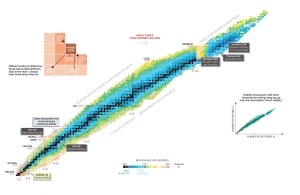

Atomic nuclei consist of protons and neutrons, which attract each other through the nuclear force, while protons repel each other via electromagnetic force due to their positive charge. These two forces compete, leading to various stability of nuclei. There are only certain combinations of neutrons and protons which form stable nuclei. Neutrons stabilize the nucleus because they attract each other and protons, which helps offset the electrical repulsion between protons. As a result, as the number of protons increases, an increasing ratio of neutrons to protons is needed to form a stable nucleus. Suppose there are too many (neutrons also obey the Pauli exclusion principle) or too few neutrons for a given number of protons. In that case, the resulting nucleus is not stable, and it undergoes radioactive decay. Unstable isotopes decay through various radioactive decay pathways, most commonly alpha decay, beta decay, or electron capture. Many other rare types of decay, such as spontaneous fission or neutron emission, are known.

The Pauli exclusion principle also influences the critical energy of fissile and fissionable nuclei. For example, actinides with odd neutron numbers are usually fissile (fissionable with slow neutrons), while actinides with even neutron numbers are not fissile (but fissionable with fast neutrons). Due to the Pauli exclusion principle, heavy nuclei with an even number of protons and an even number of neutrons are very stable thanks to the occurrence of ‘paired spin.’ On the other hand, nuclei with an odd number of protons and neutrons are mostly unstable.

Pauli Exclusion Principle and Neutron Stars

A neutron star is the collapsed core of a large star (usually of a red giant). Neutron stars are the smallest and densest stars known to exist, and they rotate extremely rapidly. A neutron star is basically a giant atomic nucleus about 11 km in diameter made especially of neutrons. It is believed that under the immense pressures of collapsing massive stars going supernova, the electrons and protons can combine to form neutrons via electron capture, releasing a huge amount of neutrinos. Since they have similar properties as atomic nuclei, neutron stars are sometimes described as giant nuclei. But be careful. Neutron stars and atomic nuclei are held together by different forces. A nucleus is held together by the strong force, while a neutron star is held together by gravitational force.

On the other hand, neutron stars are partially supported against further collapse by neutron degeneracy (via degeneracy pressure), a phenomenon described by the Pauli exclusion principle. In a highly dense state of matter, where gravitational pressure is extreme, quantum mechanical effects are significant. Degenerate matter is usually modeled as an ideal Fermi gas, in which the Pauli exclusion principle prevents identical fermions from occupying the same quantum state. Similarly, white dwarfs are supported against collapse by electron degeneracy pressure, analogous to neutron degeneracy.