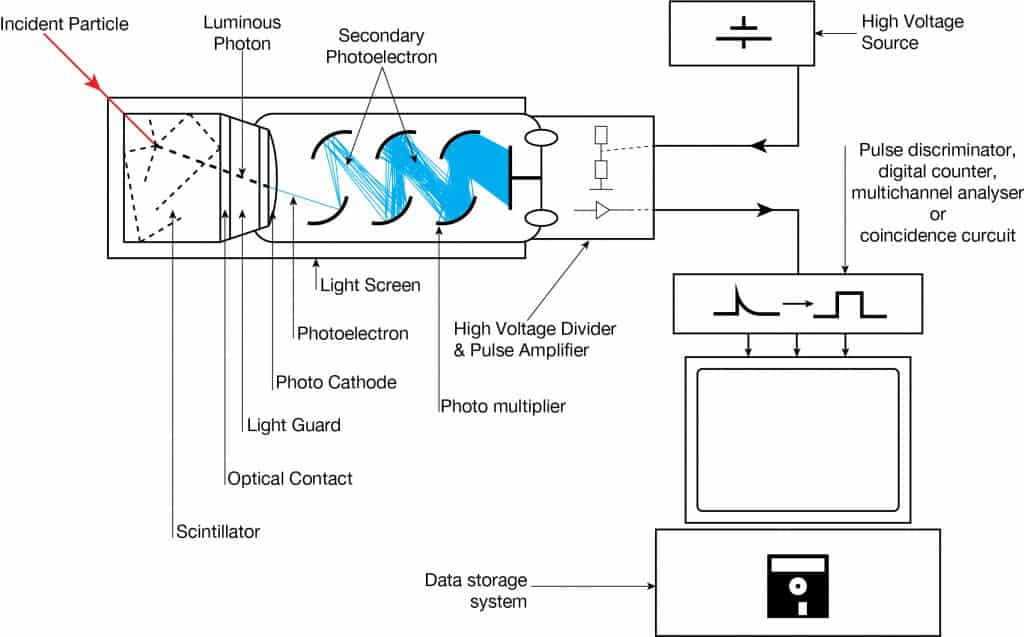

Scintillation is a flash of light produced in a transparent material by passing a particle (an electron, an alpha particle, an ion, or a high-energy photon). Scintillation occurs in the scintillator, a key part of a scintillation detector. In general, a scintillation detector consists of:

- Scintillator. A scintillator generates photons in response to incident radiation.

- Photodetector. A sensitive photodetector (usually a photomultiplier tube (PMT), a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera, or a photodiode) converts the light to an electrical signal, and electronics process this signal.

Scintillation Materials – Scintillators

Scintillators are kinds of materials that provide detectable photons in the visible part of the light spectrum, following the passage of a charged particle or a photon. The scintillator consists of a transparent crystal, usually a phosphor, plastic, or organic liquid, that fluoresces when struck by ionizing radiation. The scintillator must also be transparent to its light emissions and have a short decay time. The scintillator must also be shielded from all ambient light so that external photons do not swamp the ionization events caused by incident radiation. A thin opaque foil, such as aluminized mylar, is often used to achieve this. However, it must have a low enough mass to minimize undue attenuation of the measured incident radiation.

There are primarily two types of scintillators commonly used in nuclear and particle physics: organic or plastic scintillators and inorganic or crystalline scintillators.

Inorganic Scintillators

Inorganic scintillators are usually crystals grown in high-temperature furnaces. They include lithium iodide (LiI), sodium iodide (NaI), cesium iodide (CsI), and zinc sulfide (ZnS). NaI(Tl) (thallium-doped sodium iodide) is the most widely used scintillation material. The iodine provides most of the stopping power in sodium iodide (since it has a high Z = 53). These crystalline scintillators are characterized by high density, high atomic number, and pulse decay times of approximately 1 microsecond (~ 10-6 sec). Scintillation in inorganic crystals is typically slower than in organic ones. They exhibit high efficiency for the detection of gamma rays and are capable of handling high count rates. Inorganic crystals can be cut to small sizes and arranged in an array configuration to provide position sensitivity. This feature is widely used in medical imaging to detect X-rays or gamma rays. Inorganic scintillators are better at detecting gamma rays and X-rays than organic scintillators. This is due to their high density and atomic number, which gives a high electron density. A disadvantage of some inorganic crystals, e.g., NaI, is their hygroscopicity, a property that requires them to be housed in an airtight container to protect them from moisture.

Organic Scintillators

Organic scintillators are kinds of organic materials that provide detectable photons in the visible part of the light spectrum, following the passage of a charged particle or a photon. The scintillation mechanism in organic materials is quite different from the mechanism in inorganic crystals. In inorganic scintillators, e.g., NaI, CsI, the scintillation arises because of the structure of the crystal lattice. The fluorescence mechanism in organic materials arises from transitions in the energy levels of a single molecule. Therefore the fluorescence can be observed independently of the physical state (vapor, liquid, solid).

Organic scintillators generally have fast decay times (typically ~10-8 sec), while inorganic crystals are usually far slower (~10-6 sec), although some also have fast components in their response. There are three types of organic scintillators:

- Pure organic crystals. Pure organic crystals include crystals of anthracene, stilbene, and naphthalene. The decay time of this type of phosphor is approximately 10 nanoseconds. This type of crystal is frequently used in the detection of beta particles. They are durable, but their response is anisotropic (which spoils energy resolution when the source is not collimated). They cannot be easily machined, nor can they be grown in large sizes. Therefore they are not very often used.

- Liquid organic solutions. Liquid organic solutions are produced by dissolving an organic scintillator in a solvent.

- Plastic scintillators. Plastic phosphors are made by adding scintillation chemicals to a plastic matrix. The decay constant is the shortest of the three phosphor types, approaching 1 or 2 nanoseconds. Plastic scintillators are more appropriate for use in high-flux environments and high dose rate measurements. The plastic has a high hydrogen content. Therefore, it is useful for fast neutron detectors. It takes substantially more energy to produce a detectable photon in a scintillator than in an electron-ion pair through ionization (typically by a factor of 10). Because inorganic scintillators produce more light than organic scintillators, they are consequently better for applications at low energies.