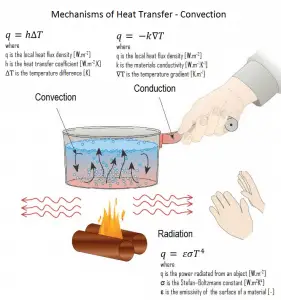

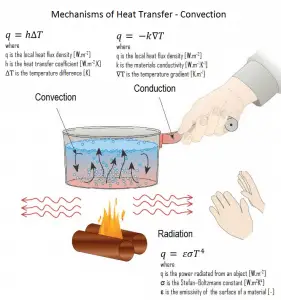

Convection takes place through advection, diffusion, or both. Heat transfer by conduction depends on the driving “force” of temperature difference.

Conduction and convection are similar in that both mechanisms require the presence of a material medium (in comparison to thermal radiation). On the other hand, they are different in that convection requires the presence of fluid motion.

In thermal conduction, energy is transferred as heat either due to the migration of free electrons or lattice vibrational waves (phonons). There is no mass movement in the direction of energy flow, and heat transfer by conduction depends on the driving “force” of temperature difference. Conduction and convection are similar in that both mechanisms require the presence of a material medium (in comparison to thermal radiation). On the other hand, they are different in that convection requires the presence of fluid motion.

At the surface, it must be emphasized that energy flow occurs purely by conduction, even in conduction. There is always a thin stagnant fluid film layer on the heat transfer surface. But in the next layers, both conduction and diffusion-mass movement occur at the molecular or macroscopic levels. Due to the mass movement, the rate of energy transfer is higher. The higher the mass movement rate, the thinner the stagnant fluid film layer will be, and the higher the heat flow rate.

It must be noted nucleate boiling at the surface effectively disrupts this stagnant layer. Therefore, nucleate boiling significantly increases the ability of a surface to transfer thermal energy to the bulk fluid.

As was written, heat transfer through a fluid is by convection in the presence of mass movement and conduction in its absence. Therefore, thermal conduction in a fluid can be viewed as the limiting case of convection, corresponding to the case of quiescent fluid.

Convection as a Conduction with Fluid Motion

Some experts do not consider convection to be a fundamental mechanism of heat transfer since it is essentially heat conduction in the presence of fluid motion. They consider it a special case of thermal conduction, known as “conduction with fluid motion”. On the other hand, it is practical to recognize convection as a separate heat transfer mechanism despite the valid arguments to the contrary.

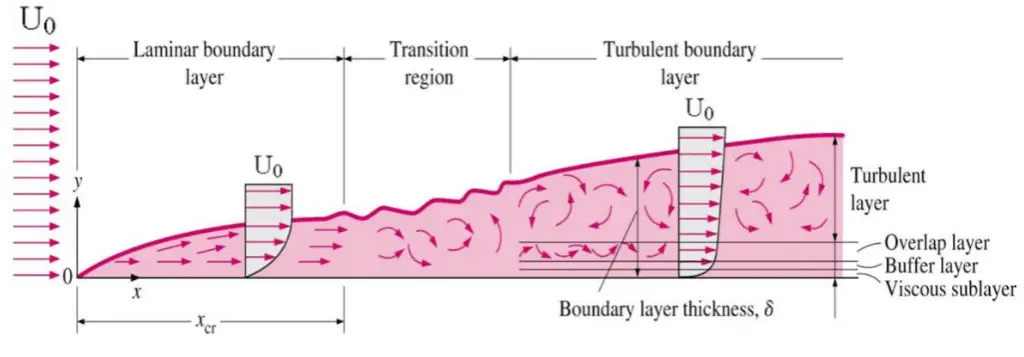

Velocity Boundary Layer

In general, when a fluid flows over a

stationary surface, e.g., the flat plate, the bed of a river, or the wall of a pipe, the fluid touching the surface is brought to

rest by the

shear stress to at the wall. The boundary layer is the region in which flow adjusts from zero velocity at the wall to a maximum in the mainstream of the flow. The concept of boundary layers is important in all viscous fluid dynamics and heat transfer theory.

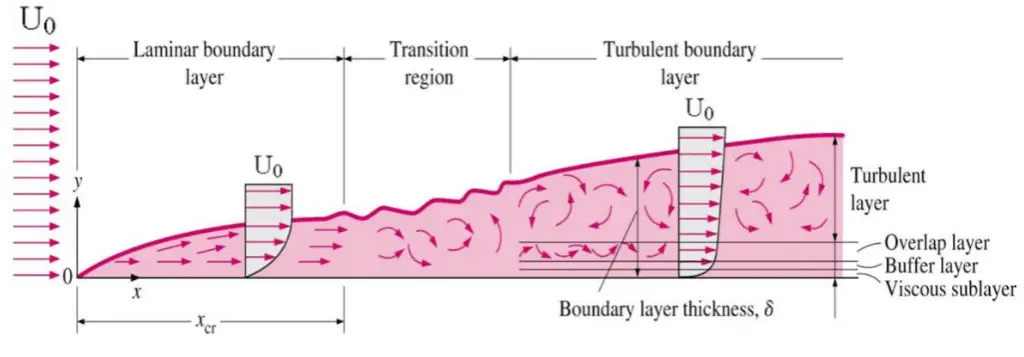

Basic characteristics of all laminar and turbulent boundary layers are shown in the developing flow over a flat plate. The stages of the formation of the boundary layer are shown in the figure below:

Boundary layers may be either laminar or turbulent, depending on the value of the Reynolds number.

See also: Boundary Layer

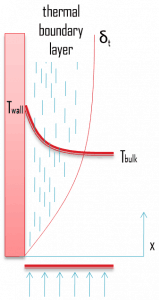

Thermal Boundary Layer

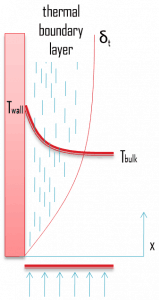

Similarly, as a

velocity boundary layer develops when there is fluid flow over a surface, a

thermal boundary layer must develop if the bulk temperature and surface temperature differ. Consider flow over an isothermal flat plate at a constant temperature of

Twall. At the leading edge, the temperature profile is uniform with

Tbulk. Fluid particles that come into contact with the plate achieve thermal equilibrium at the plate’s surface temperature. At this point, energy flow occurs at the surface

purely by conduction. These particles exchange energy with those in the adjoining fluid layer (by conduction and diffusion), and temperature gradients develop in the fluid. The fluid region in which these temperature gradients exist is the

thermal boundary layer. Its

thickness,

δt, is typically defined as the distance from the body at which the temperature is 99% of the temperature found from an inviscid solution. With increasing distance from the leading edge, heat transfer effects penetrate farther into the stream, and the thermal boundary layer grows.

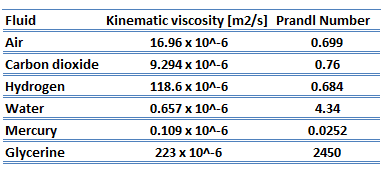

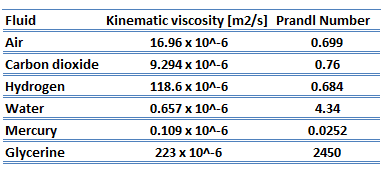

The ratio of these two thicknesses (velocity and thermal boundary layers) is governed by the Prandtl number, defined as the ratio of momentum diffusivity to thermal diffusivity. A Prandtl number of unity indicates that momentum and thermal diffusivity are comparable, and velocity and thermal boundary layers almost coincide with each other. If the Prandtl number is less than 1, which is the case for air at standard conditions, the thermal boundary layer is thicker than the velocity boundary layer. If the Prandtl number is greater than 1, the thermal boundary layer is thinner than the velocity boundary layer. Air at room temperature has a Prandtl number of 0.71, and for water, at 18°C, it is around 7.56, which means that the thermal diffusivity is more dominant for air than for water.

The ratio of these two thicknesses (velocity and thermal boundary layers) is governed by the Prandtl number, defined as the ratio of momentum diffusivity to thermal diffusivity. A Prandtl number of unity indicates that momentum and thermal diffusivity are comparable, and velocity and thermal boundary layers almost coincide with each other. If the Prandtl number is less than 1, which is the case for air at standard conditions, the thermal boundary layer is thicker than the velocity boundary layer. If the Prandtl number is greater than 1, the thermal boundary layer is thinner than the velocity boundary layer. Air at room temperature has a Prandtl number of 0.71, and for water, at 18°C, it is around 7.56, which means that the thermal diffusivity is more dominant for air than for water.

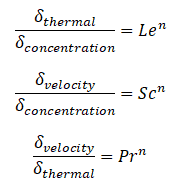

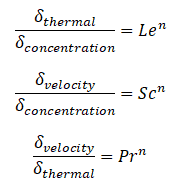

Similarly, as for Prandtl Number, the Lewis number physically relates the relative thickness of the thermal layer and mass-transfer (concentration) boundary layer. The Schmidt number physically relates the relative thickness of the velocity boundary layer and mass-transfer (concentration) boundary layer.

where n = 1/3 for most applications in all three relations. These relations, in general, are applicable only for laminar flow and do not apply to turbulent boundary layers since turbulent mixing, in this case, may dominate the diffusion processes.

Heat transfer by convection is more difficult to analyze than heat transfer by conduction because no single property of the heat transfer medium, such as thermal conductivity, can be defined to describe the mechanism. Convective heat transfer is complicated by the fact that it involves fluid motion as well as heat conduction. Heat transfer by convection varies from situation to situation (upon the fluid flow conditions), and it is frequently coupled with the mode of fluid flow. In forced convection, the heat transfer rate through a fluid is much higher by convection than by conduction.

In practice, analysis of heat transfer by convection is treated empirically (by direct experimental observation). Most problems can be solved using so-called characteristic numbers (e.g., Nusselt number). Characteristic numbers are dimensionless numbers used to describe a character of heat transfer. They can be used to compare a real situation (e.g., heat transfer in a pipe) with a small-scale model. Experience shows that convection heat transfer strongly depends on the fluid properties, dynamic viscosity, thermal conductivity, density, and specific heat, as well as the fluid velocity. It also depends on the geometry and the roughness of the solid surface, and the type of fluid flow. All these conditions affect especially the stagnant film thickness.

Convection involves heat transfer between a surface at a given temperature (Twall) and fluid at a bulk temperature (Tb). The exact definition of the bulk temperature (Tb) varies depending on the details of the situation.

- For flow adjacent to a hot or cold surface, Tb is the temperature of the fluid “far” from the surface.

- For boiling or condensation, Tb is the saturation temperature of the fluid.

- For flow in a pipe, Tb is the average temperature measured at a particular cross-section of the pipe.

References:

Heat Transfer:

- Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 7th Edition. Theodore L. Bergman, Adrienne S. Lavine, Frank P. Incropera. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2011. ISBN: 9781118137253.

- Heat and Mass Transfer. Yunus A. Cengel. McGraw-Hill Education, 2011. ISBN: 9780071077866.

- Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer. C. P. Kothandaraman. New Age International, 2006, ISBN: 9788122417722.

- U.S. Department of Energy, Thermodynamics, Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow. DOE Fundamentals Handbook, Volume 2 of 3. May 2016.

Nuclear and Reactor Physics:

- J. R. Lamarsh, Introduction to Nuclear Reactor Theory, 2nd ed., Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA (1983).

- J. R. Lamarsh, A. J. Baratta, Introduction to Nuclear Engineering, 3d ed., Prentice-Hall, 2001, ISBN: 0-201-82498-1.

- W. M. Stacey, Nuclear Reactor Physics, John Wiley & Sons, 2001, ISBN: 0- 471-39127-1.

- Glasstone, Sesonske. Nuclear Reactor Engineering: Reactor Systems Engineering, Springer; 4th edition, 1994, ISBN: 978-0412985317

- W.S.C. Williams. Nuclear and Particle Physics. Clarendon Press; 1 edition, 1991, ISBN: 978-0198520467

- G.R.Keepin. Physics of Nuclear Kinetics. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co; 1st edition, 1965

- Robert Reed Burn, Introduction to Nuclear Reactor Operation, 1988.

- U.S. Department of Energy, Nuclear Physics and Reactor Theory. DOE Fundamentals Handbook, Volume 1 and 2. January 1993.

- Paul Reuss, Neutron Physics. EDP Sciences, 2008. ISBN: 978-2759800414.

Advanced Reactor Physics:

- K. O. Ott, W. A. Bezella, Introductory Nuclear Reactor Statics, American Nuclear Society, Revised edition (1989), 1989, ISBN: 0-894-48033-2.

- K. O. Ott, R. J. Neuhold, Introductory Nuclear Reactor Dynamics, American Nuclear Society, 1985, ISBN: 0-894-48029-4.

- D. L. Hetrick, Dynamics of Nuclear Reactors, American Nuclear Society, 1993, ISBN: 0-894-48453-2.

- E. E. Lewis, W. F. Miller, Computational Methods of Neutron Transport, American Nuclear Society, 1993, ISBN: 0-894-48452-4.