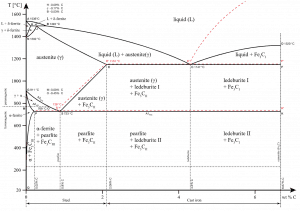

Austenite, also known as gamma-phase iron (γ-Fe), is a non-magnetic face-centered cubic structure phase of iron. Austenite in iron-carbon alloys is generally only present above the critical eutectoid temperature (723°C) and below 1500°C, depending on carbon content. However, it can be retained to room temperature by alloy additions such as nickel or manganese.

Carbon plays an important role in heat treatment because it expands the temperature range of austenite stability. Higher carbon content lowers the temperature needed to austenitize steel—such that iron atoms rearrange themselves to form an fcc lattice structure. Austenite is present in the most commonly used type of stainless steel, which is very well known for its corrosion resistance.

Austenitic Stainless Steel

Austenitic stainless steels contain between 16 and 25% of chromium and can also contain nitrogen in solution, which contributes to their relatively high corrosion resistance. Austenitic stainless steels are classified with AISI 200- or 300-series designations; the 300-series grades are chromium-nickel alloys, and the 200-series represent a set of compositions in which manganese and/or nitrogen replace some of the nickel.

Austenitic stainless steels have the best corrosion resistance of all stainless steels, and they have excellent cryogenic properties and good high-temperature strength. They possess a face-centered cubic (fcc) microstructure that is non-magnetic and can be easily welded. This austenite crystalline structure is achieved by sufficient additions of the austenite stabilizing elements nickel, manganese, and nitrogen. Austenitic stainless steel is the largest family of stainless steel, making up two-thirds of all stainless steel production. Their yield strength is low (200 to 300MPa), which limits their use for structural and other load-bearing components. They cannot be hardened by heat treatment but have the useful property of being work-hardened to high strength levels while retaining a useful level of ductility and toughness. Duplex stainless steels tend to be preferred in such situations because of their high strength and corrosion resistance. The best-known grade is AISI 304 stainless, which contains chromium (between 15% and 20%) and nickel (between 2% and 10.5%) metals as the main non-iron constituents. 304 stainless steel has excellent resistance to a wide range of atmospheric environments and many corrosive media. Cold forming usually characterizes these alloys as ductile, weldable, and hardenable.

Austenitic stainless steels have the best corrosion resistance of all stainless steels, and they have excellent cryogenic properties and good high-temperature strength. They possess a face-centered cubic (fcc) microstructure that is non-magnetic and can be easily welded. This austenite crystalline structure is achieved by sufficient additions of the austenite stabilizing elements nickel, manganese, and nitrogen. Austenitic stainless steel is the largest family of stainless steel, making up two-thirds of all stainless steel production. Their yield strength is low (200 to 300MPa), which limits their use for structural and other load-bearing components. They cannot be hardened by heat treatment but have the useful property of being work-hardened to high strength levels while retaining a useful level of ductility and toughness. Duplex stainless steels tend to be preferred in such situations because of their high strength and corrosion resistance. The best-known grade is AISI 304 stainless, which contains chromium (between 15% and 20%) and nickel (between 2% and 10.5%) metals as the main non-iron constituents. 304 stainless steel has excellent resistance to a wide range of atmospheric environments and many corrosive media. Cold forming usually characterizes these alloys as ductile, weldable, and hardenable.

Other Common Phases in Steels and Irons

Heat treatment of steels requires an understanding of both the equilibrium phases and the metastable phases that occur during heating and/or cooling. For steels, the stable equilibrium phases include:

- Ferrite. Ferrite or α-ferrite is a body-centered cubic structure phase of iron that exists below temperatures of 912°C for low concentrations of carbon in iron. α-ferrite can only dissolve up to 0.02 percent of carbon at 727°C. This is because of the configuration of the iron lattice, which forms a BCC crystal structure. The primary phase of low-carbon or mild steel and most cast irons at room temperature is ferromagnetic α-Fe.

- Austenite. Austenite, also known as gamma-phase iron (γ-Fe), is a non-magnetic face-centered cubic structure phase of iron. Austenite in iron-carbon alloys is generally only present above the critical eutectoid temperature (723°C) and below 1500°C, depending on carbon content. However, it can be retained to room temperature by alloy additions such as nickel or manganese. Carbon plays an important role in heat treatment because it expands the temperature range of austenite stability. Higher carbon content lowers the temperature needed to austenitize steel—such that iron atoms rearrange themselves to form an fcc lattice structure. Austenite is present in the most commonly used type of stainless steel, which is very well known for its corrosion resistance.

- Graphite. Adding a small amount of non-metallic carbon to iron trades its great ductility for greater strength.

- Cementite. Cementite (Fe3C) is a metastable compound, and under some circumstances, it can be made to dissociate or decompose to form α-ferrite and graphite, according to the reaction: Fe3C → 3Fe (α) + C (graphite). Cementite, in its pure form, is ceramic and is hard and brittle, making it suitable for strengthening steel. Its mechanical properties are a function of its microstructure, which depends upon how it is mixed with ferrite.

The metastable phases are:

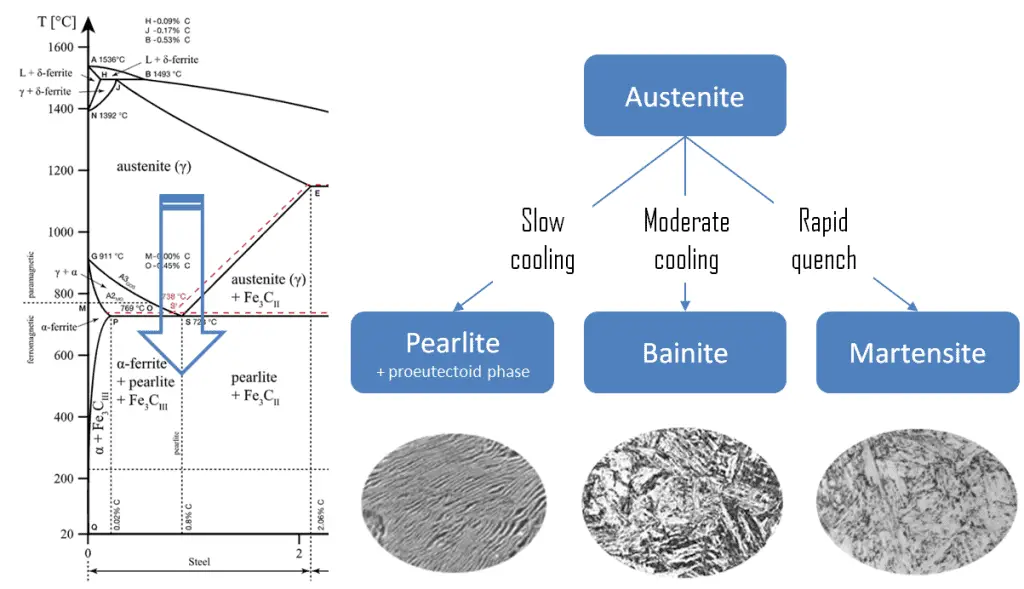

Pearlite. In metallurgy, pearlite is a layered metallic structure of two phases, composed of alternating layers of ferrite (87.5 wt%) and cementite (12.5 wt%) that occurs in some steels and cast irons. It is named for its resemblance to the mother of the pearl.

Pearlite. In metallurgy, pearlite is a layered metallic structure of two phases, composed of alternating layers of ferrite (87.5 wt%) and cementite (12.5 wt%) that occurs in some steels and cast irons. It is named for its resemblance to the mother of the pearl.- Martensite. Martensite is a very hard metastable structure with a body-centered tetragonal (BCT) crystal structure. Martensite is formed in steels when austenite’s cooling rate is so high that carbon atoms do not have time to diffuse out of the crystal structure in large enough quantities to form cementite (Fe3C).

- Bainite. Bainite is a plate-like microstructure that forms in steels from austenite when cooling rates are not rapid

enough to produce martensite but are still fast enough so that carbon does not have enough time to diffuse to form pearlite. Bainitic steels are generally stronger and harder than pearlitic steels, yet they exhibit a desirable combination of strength and ductility.