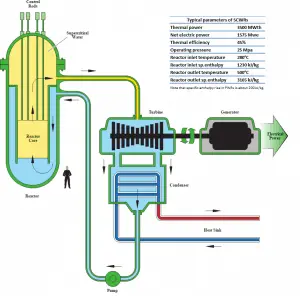

The layout of nuclear power plants comprises two major parts: The nuclear island and the conventional (turbine) island. The nuclear island is the heart of the nuclear power plant. On the other hand, the conventional (turbine) island houses the key component which extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and converts it into electrical energy, the turbine generator. Therefore it is also known as the power conversion system. The key device of the power conversion system is the turbine generator. The turbine generator is in the turbine building and contains most of the main components of the thermodynamic cycle. Only the steam generators are situated in the reactor building (the nuclear island).

Note that we are describing the power conversion system of a pressurized water reactor (PWR). A boiling water reactor (BWR) is like a pressurized water reactor but with many differences. The BWRs don’t have any steam generators. Unlike a PWR, there is no primary and secondary loop. The turbine island of BWRs is very similar to PWRs.

Since the conventional power plants (e.g.,, fossil-fuel power plants) use very similar technology to convert thermal energy into electrical energy, this nuclear power plant is called a “conventional island”. In comparison to conventional power plants, the conventional island at nuclear power plants must fulfill the significantly stricter specification on quality assurance and control that applies to even conventional parts of the nuclear power plant due to their impact on the nuclear systems.

The key components of power conversion system:

- Steam Turbine. A steam turbine is a device that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft.

- Generator. A generator is a device that converts the mechanical energy of the steam turbine to electrical energy.

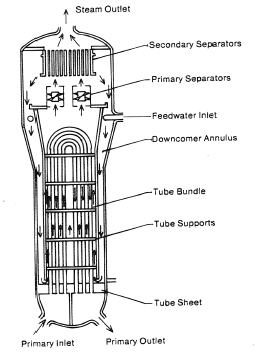

- Steam Generator. Steam generators are heat exchangers that convert feedwater into steam from heat produced in a nuclear reactor core.

- Condenser. A condenser is a heat exchanger used to condense steam from the last stage of the turbine.

- Condensate-Feedwater System. Condensate-Feedwater Systems have two major functions. To supply adequate high-quality water (condensate) to the steam generator and heat the water (condensate) to a temperature close to saturation.

- Moisture Separator Reheater (MSR). The moisture separator reheaters are usually installed between the high-pressure turbine outlet and the low-pressure turbine inlets to remove the moisture from the high-pressure turbine exhaust steam and reheat this steam before being admitted to the LP turbines.

- Cooling System. The primary function of the cooling system in power plants is to cool the steam circuit to condense the low-pressure steam and recycle it. As the steam in the internal circuit condenses back to the water, the surplus (waste) heat removed from it needs to be discharged by transfer to the air or a body of water.

- Instrumentation and Control System (I&C). The instrumentation and control system serves as the central nervous system of a nuclear power plant.

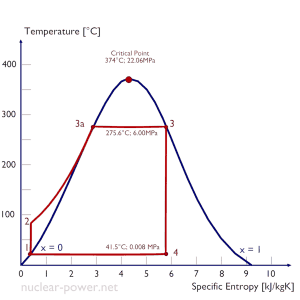

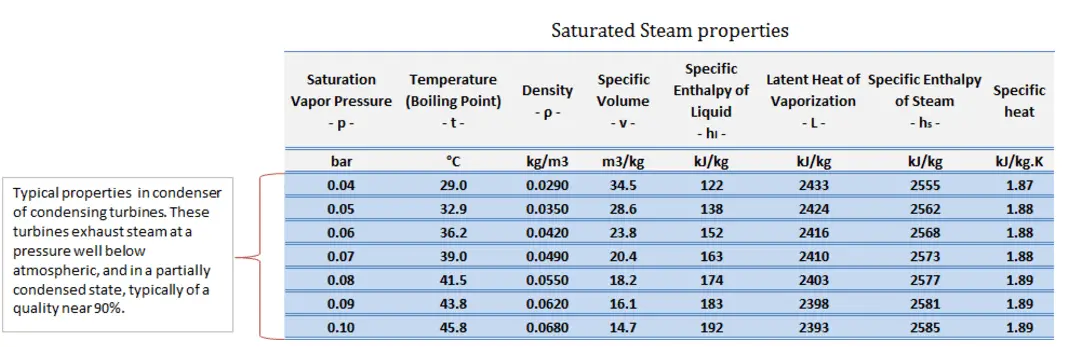

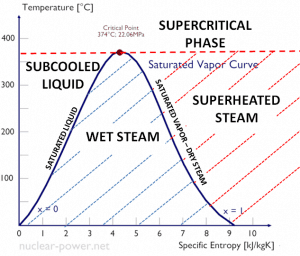

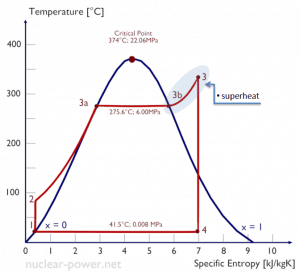

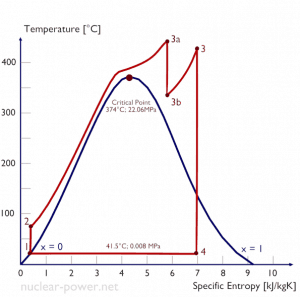

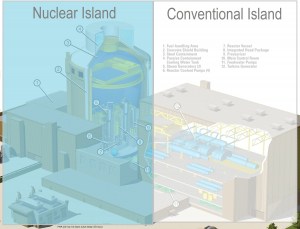

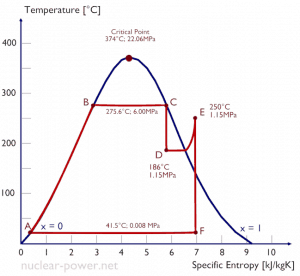

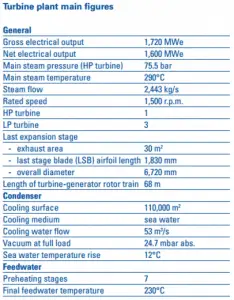

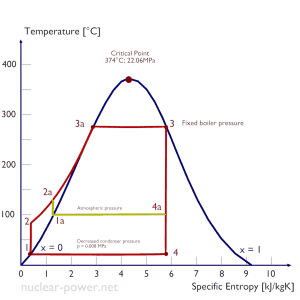

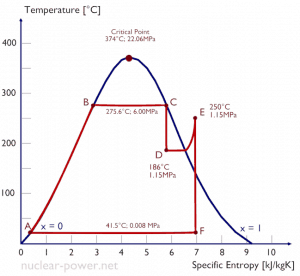

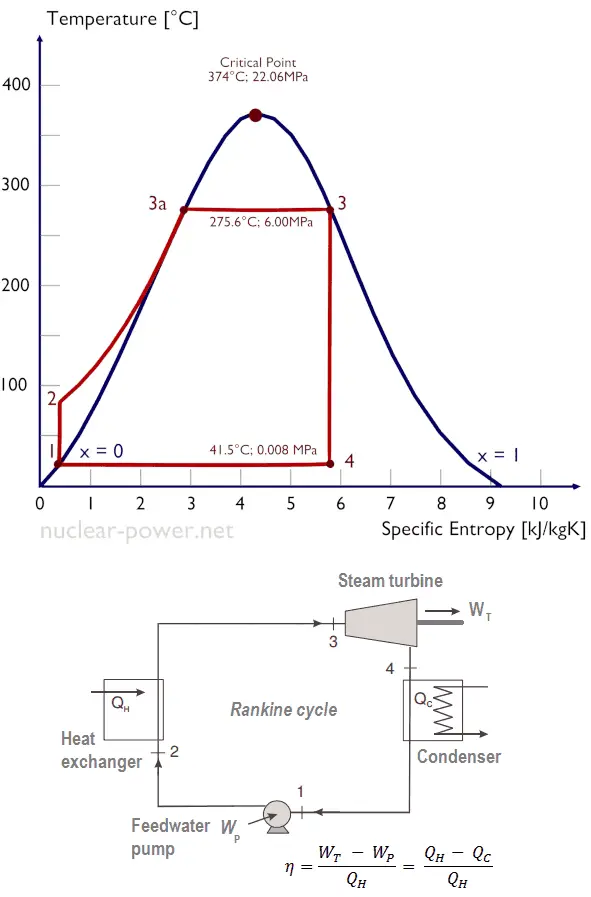

Ts diagram of the Rankine cycle. The Rankine cycle was named after a Scottish engineer, William John Macquorn Rankine, and describes the performance of steam turbine systems.

Principle of Operation of Turbine Generator – Electricity Generation

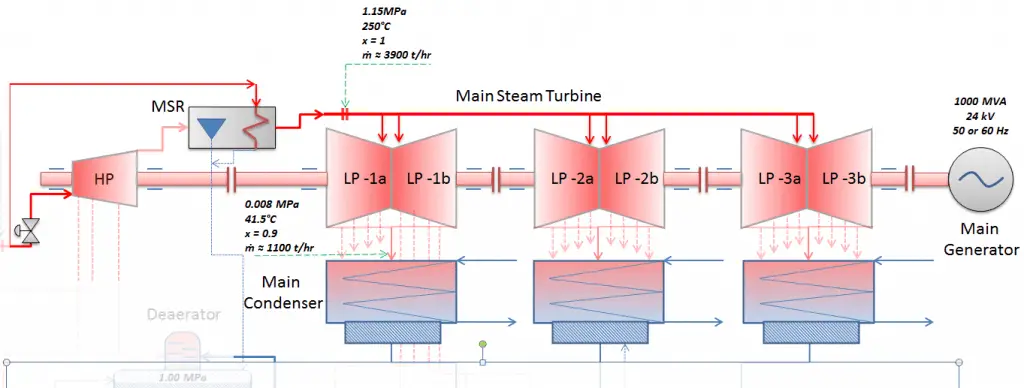

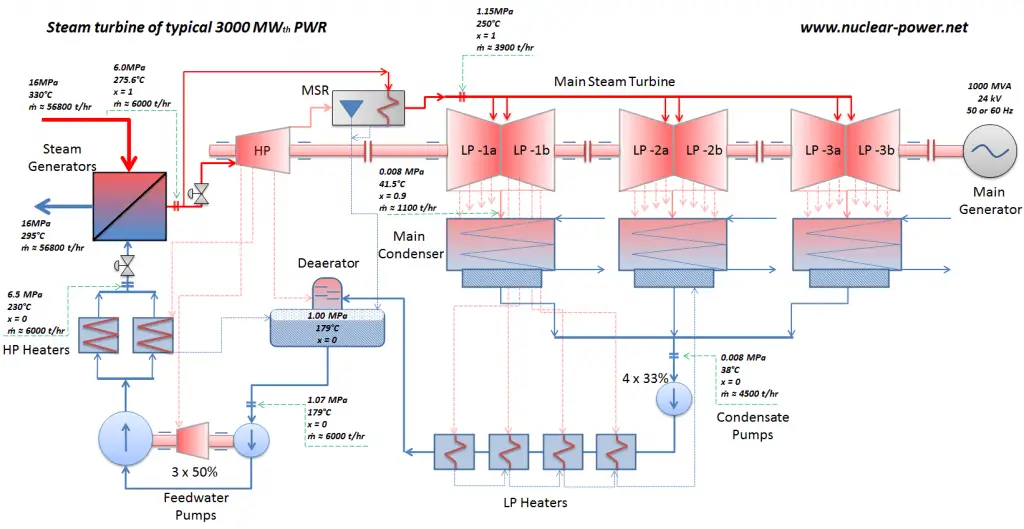

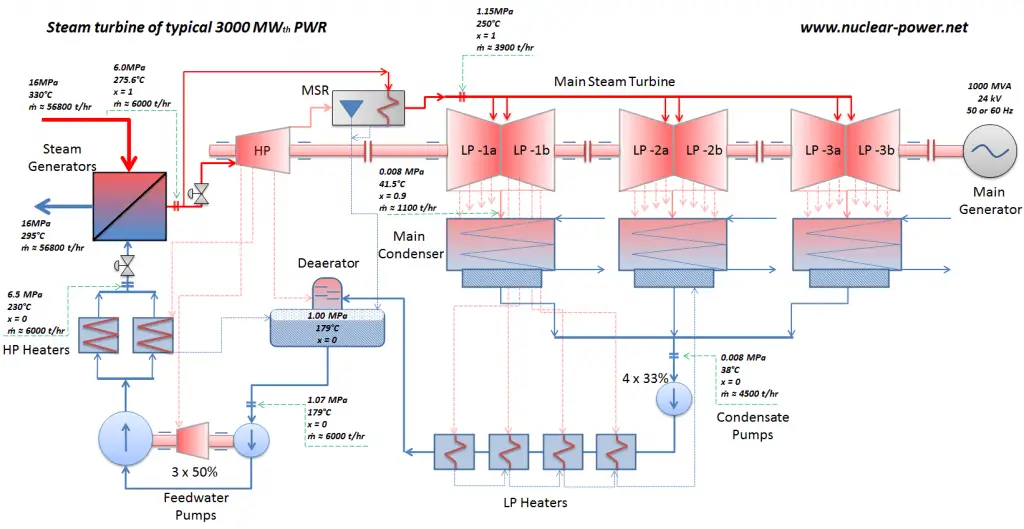

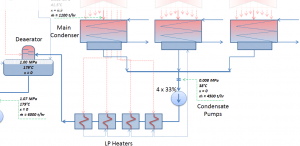

Most nuclear power plants operate a single-shaft turbine-generator that consists of one multi-stage HP turbine and three parallel multi-stage LP turbines, the main generator and an exciter. HP Turbine is usually a double-flow impulse turbine (or reaction type) with about 10 stages with shrouded blades and produces about 30-40% of the gross power output of the power plant unit. LP turbines are usually double-flow reaction turbines with about 5-8 stages (with shrouded blades and free-standing blades of the last 3 stages). LP turbines produce approximately 60-70% of the gross power output of the power plant unit. Each turbine rotor is mounted on two bearings, i.e., there are double bearings between each turbine module.

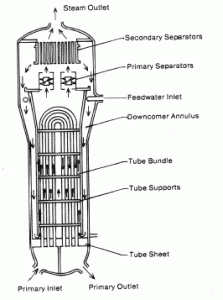

From Steam Generator to Main Steam Lines – Evaporation

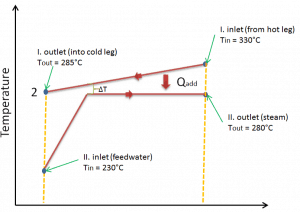

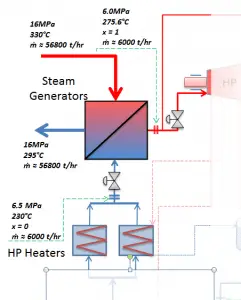

The power conversion system of typical PWR begins in the steam generators in their shell sides. Steam generators are heat exchangers that convert feedwater into steam from heat produced in a nuclear reactor core. The feedwater (secondary circuit) is heated from ~230°C 500°F (preheated fluid by regenerators) to the boiling point of that fluid (280°C; 536°F; 6,5MPa). Heat is transferred through the walls of these tubes to the lower pressure secondary coolant located on the secondary side of the exchanger where the coolant evaporates to pressurized steam (saturated steam 280°C; 536°F; 6,5 MPa). The saturated steam leaves the steam generator through a steam outlet and continues to the main steam lines and further to the steam turbine.

These main steam lines are cross-tied (e.g.,, via steam collector pipe) near the turbine to ensure that the pressure difference between any steam generators does not exceed a specific value, thus maintaining system balance and ensuring uniform heat removal from the Reactor Coolant System (RCS). The steam flows through the main steam line isolation valves (MSIVs), which are very important to the high-pressure turbine from a safety point of view. Directly at the inlet of the steam turbine, there are throttle-stop valves and control valves. Turbine control is achieved by varying these turbine valves openings. In the event of a turbine trip, the steam supply must be isolated very quickly, usually in a fraction of a second, so the stop valves must operate quickly and reliably.

These main steam lines are cross-tied (e.g.,, via steam collector pipe) near the turbine to ensure that the pressure difference between any steam generators does not exceed a specific value, thus maintaining system balance and ensuring uniform heat removal from the Reactor Coolant System (RCS). The steam flows through the main steam line isolation valves (MSIVs), which are very important to the high-pressure turbine from a safety point of view. Directly at the inlet of the steam turbine, there are throttle-stop valves and control valves. Turbine control is achieved by varying these turbine valves openings. In the event of a turbine trip, the steam supply must be isolated very quickly, usually in a fraction of a second, so the stop valves must operate quickly and reliably.

From Turbine Valves to Condenser – Expansion

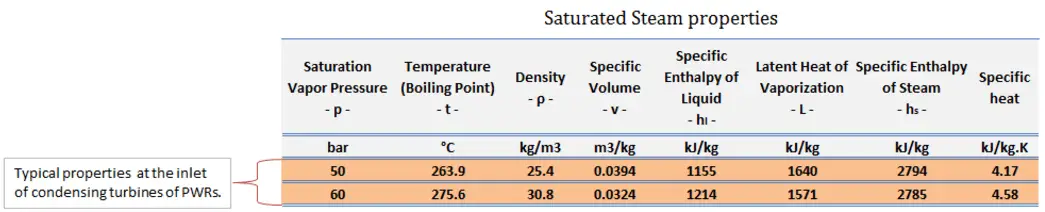

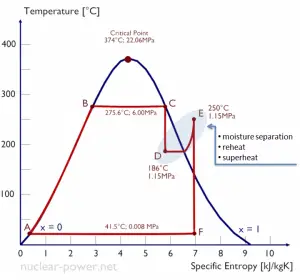

Typically most nuclear power plants operate multi-stage condensing steam turbines. In these turbines, the high-pressure stage receives steam (this steam is nearly saturated steam – x = 0.995 – point C at the figure; 6 MPa; 275.6°C) from a steam generator and exhausts it to moisture separator-reheater (MSR – point D). The steam must be reheated to avoid damages caused to the steam turbine blades by low-quality steam. High content of water droplets can cause rapid impingement and erosion of the blades, which occurs when condensed water is blasted onto the blades. To prevent this, condensate drains are installed in the steam piping leading to the turbine. The moisture-free steam is superheated by extraction steam from the high-pressure stage of the turbine and by steam directly from the main steam lines.

The heating steam is condensed in the tubes and is drained to the feedwater system. The reheater heats the steam (point D), and then the steam is directed to the low-pressure stage of the steam turbine, where it expands (point E to F). The exhausted steam then condenses in the condenser. It is at a pressure well below atmospheric (absolute pressure of 0.008 MPa) and is in a partially condensed state (point F), typically of a quality near 90%. The turbine’s high pressure and low-pressure stages are usually on the same shaft to drive a common generator, but they have separate cases. The main generator produces electrical power, which is supplied to the electrical grid.

From Condenser to Condensate Pumps – Condensation

The main condenser condenses the exhaust steam from the main turbine’s low-pressure stages and the steam dump system. The exhausted steam is condensed by passing over tubes containing water from the cooling system.

The main condenser condenses the exhaust steam from the main turbine’s low-pressure stages and the steam dump system. The exhausted steam is condensed by passing over tubes containing water from the cooling system.

The pressure inside the condenser is given by the ambient air temperature (i.e., water temperature in the cooling system) and by steam ejectors or vacuum pumps, which pull the gases (non-condensable) from the surface condenser eject them to the atmosphere.

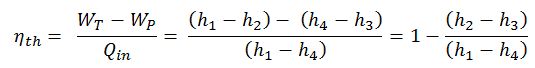

The lowest feasible condenser pressure is the saturation pressure corresponding to the ambient temperature (e.g.,, the absolute pressure of 0.008 MPa, which corresponds to 41.5°C). Note that there is always a temperature difference between (around ΔT = 14°C) the condenser temperature and the ambient temperature, which originates from condensers’ finite size and efficiency. Since neither the condenser is a 100% efficient heat exchanger, there is always a temperature difference between the saturation temperature (secondary side) and the temperature of the coolant in the cooling system. Moreover, there is design inefficiency, which decreases the overall efficiency of the turbine. Ideally, the steam exhausted into the condenser would have no subcooling. But real condensers are designed to subcool the liquid by a few degrees Celsius to avoid the suction cavitation in the condensate pumps. But, this subcooling increases the inefficiency of the cycle because more energy is needed to reheat the water.

The goal of maintaining the lowest practical turbine exhaust pressure is a primary reason for including the condenser in a thermal power plant. The condenser provides a vacuum that maximizes the energy extracted from the steam, resulting in a significant increase in network and thermal efficiency. But also this parameter (condenser pressure) has its engineering limits:

- Decreasing the turbine exhaust pressure decreases the vapor quality (or dryness fraction). At some point, the expansion must be ended to avoid damages caused to steam turbine blades by low-quality steam.

- Decreasing the turbine exhaust pressure significantly increases the specific volume of exhausted steam, which requires huge blades in the last rows of the low-pressure stage of the steam turbine.

In a typical wet steam turbine, the exhausted steam condenses in the condenser, and it is at a pressure well below atmospheric (absolute pressure of 0.008 MPa, which corresponds to 41.5°C). This steam is in a partially condensed state (point F), typically of a quality near 90%. Note that the pressure inside the condenser is also dependent on the ambient atmospheric conditions:

- air temperature, pressure, and humidity in case of cooling into the atmosphere

- water temperature and the flow rate in case of cooling into a river or sea

An increase in the ambient temperature causes a proportional increase in pressure of exhausted steam (ΔT = 14°C is usually a constant); hence the thermal efficiency of the power conversion system decreases. In other words, the electrical output of a power plant may vary with ambient conditions, while the thermal power remains constant.

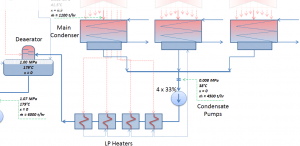

The condensed steam (now called condensate) is collected in the condenser’s hotwell. The condenser’s hotwell also provides a water storage capacity required for operational purposes such as feedwater makeup. The condensate (saturated or slightly subcooled liquid) is delivered to the condensate pump and then pumped by condensate pumps to the deaerator through a feedwater heating system. The condensate pumps increase the pressure usually to about p = 1-2 MPa. There are usually four one-third-capacity centrifugal condensate pumps with common suction and discharge headers. Three pumps are normally in operation, with one in the backup.

From Condensate Pumps to Feedwater Pumps – Heat Regeneration

The condensate from condensate pumps then passes through several stages of low-pressure feedwater heaters. The temperature of the condensate is increased by heat transfer from steam extracted from the low-pressure turbines. There are usually three or four stages of low-pressure feedwater heaters connected in the cascade. The condensate exits the low-pressure feedwater heaters at approximately p = 1 MPa, t = 150°C, entering the deaerator. The main condensate system also contains a mechanical condensate purification system for removing impurities. The feedwater heaters are self-regulating. It means that the greater the flow of feedwater, the greater the rate of heat absorption from the steam and the greater the flow of extraction steam.

The condensate from condensate pumps then passes through several stages of low-pressure feedwater heaters. The temperature of the condensate is increased by heat transfer from steam extracted from the low-pressure turbines. There are usually three or four stages of low-pressure feedwater heaters connected in the cascade. The condensate exits the low-pressure feedwater heaters at approximately p = 1 MPa, t = 150°C, entering the deaerator. The main condensate system also contains a mechanical condensate purification system for removing impurities. The feedwater heaters are self-regulating. It means that the greater the flow of feedwater, the greater the rate of heat absorption from the steam and the greater the flow of extraction steam.

There are non-return valves in the extraction steam lines between the feedwater heaters and the turbine. These non-return valves prevent the reverse steam or water flow in case of turbine trip, which causes a rapid decrease in the pressure inside the turbine. Any water entering the turbine in this way could cause severe damage to the turbine blading.

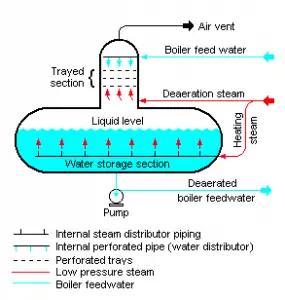

Deaerator

In general, a deaerator is a device used to remove oxygen and other dissolved gases from the feedwater to steam generators. The deaerator is part of the feedwater heating system. It is usually situated between the last low-pressure heater and feedwater booster pumps. In particular, dissolved oxygen in the steam generator can cause serious corrosion damage by attaching to the walls of metal piping and other metallic equipment and forming oxides (rust). Furthermore, dissolved carbon dioxide combines with water to form carbonic acid that causes further corrosion.

The condensate is heated to saturated conditions in the deaerator, usually by the steam extracted from the steam turbine. The extraction steam is mixed in the deaerator by a system of spray nozzles and cascading trays between which the steam percolates. Any dissolved gases in the condensate are released in this process and removed from the deaerator by venting to the atmosphere or the main condenser. Directly below the deaerator is the feedwater storage tank, in which a large quantity of feedwater is stored at near saturation conditions. This feedwater can be supplied to steam generators to maintain the required water inventory during the transient in the turbine trip event. The deaerator and storage tank are usually located at a high elevation in the turbine hall to ensure an adequate net positive suction head (NPSH) to the feedwater pumps at the inlet. NPSH is used to measure how close a fluid is to saturated conditions. Lowering the pressure at the suction side can induce cavitation. This arrangement minimizes the risk of cavitation in the pump.

From Feedwater Pumps to Steam Generator

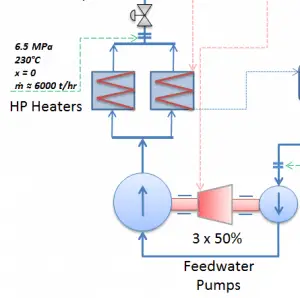

The system of feedwater pumps usually contains three parallel lines (3×50%) of feedwater pumps with common suction and discharge headers. Each feedwater pump consists of the booster and the main feedwater pump. The feed water pumps (usually driven by steam turbines) increase the pressure of the condensate (~1MPa) to the pressure in the steam generator (~6.5MPa).

The system of feedwater pumps usually contains three parallel lines (3×50%) of feedwater pumps with common suction and discharge headers. Each feedwater pump consists of the booster and the main feedwater pump. The feed water pumps (usually driven by steam turbines) increase the pressure of the condensate (~1MPa) to the pressure in the steam generator (~6.5MPa).

The booster pumps provide the required main feedwater pump suction pressure. These pumps (both feedwater pumps) are normally high-pressure pumps (usually of the centrifugal pump type) that take suction from the deaerator water storage tank, which is mounted directly below the deaerator, and supply the main feedwater pumps. The water discharge from the feedwater pumps flows through the high-pressure feedwater heaters, enters the containment, and then flows into the steam generators.

Feedwater flow to each steam generator is controlled by feedwater regulating valves (FRVs) in each feedwater line. The regulator is controlled automatically by steam generator level, steam flow, and feedwater flow.

The high-pressure feedwater heaters are heated by extraction steam from the high-pressure turbine, HP Turbine. Drains from the high-pressure feedwater heaters are usually routed to the deaerator.

The feedwater (water 230°C; 446°F; 6,5MPa) is pumped into the steam generator through the feedwater inlet. In the steam generator is the feedwater (secondary circuit) heated from ~230°C 446°F to the boiling point of that fluid (280°C; 536°F; 6,5MPa). Feedwater is then evaporated, and the pressurized steam (saturated steam 280°C; 536°F; 6,5 MPa) leaves the steam generator through the steam outlet and continues to the steam turbine, thereby completing the cycle.

Thermal Efficiency of Steam Turbines

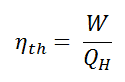

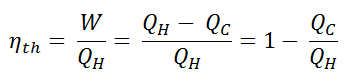

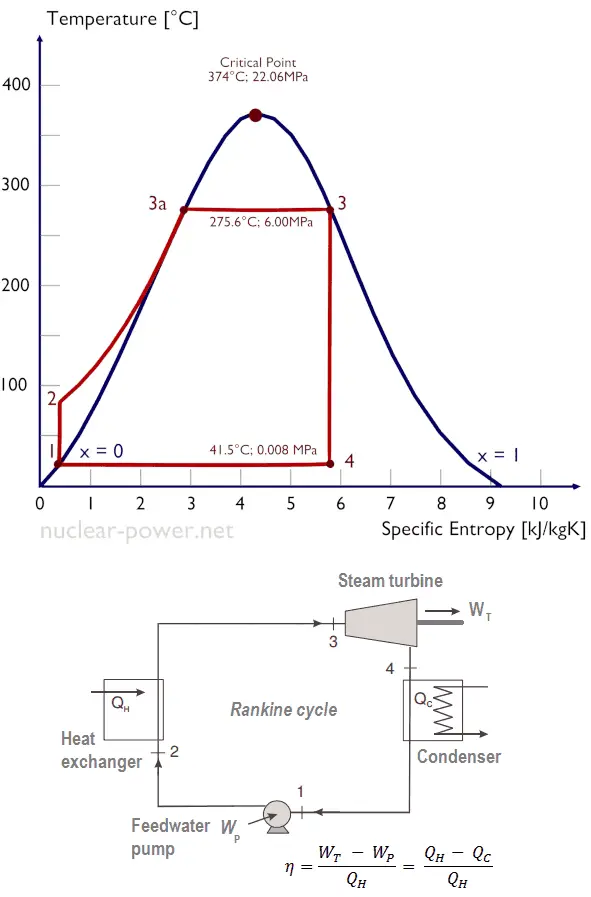

In general, the thermal efficiency, ηth, of any heat engine is defined as the ratio of the work it does, W, to the heat input at the high temperature, QH.

The thermal efficiency, ηth, represents the fraction of heat, QH, converted to work. Since energy is conserved according to the first law of thermodynamics and energy cannot be converted to work completely, the heat input, QH, must equal the work done, W, plus the heat that must be dissipated as waste heat QC into the environment. Therefore we can rewrite the formula for thermal efficiency as:

This is a very useful formula, but we express the thermal efficiency using the first law in terms of enthalpy.

Typically most nuclear power plants operate multi-stage condensing steam turbines. In these turbines, the high-pressure stage receives steam (this steam is nearly saturated steam – x = 0.995 – point C at the figure; 6 MPa; 275.6°C) from a steam generator and exhausts it to moisture separator-reheater (point D). The steam must be reheated to avoid damages caused to the steam turbine blades by low-quality steam. The reheater heats the steam (point D), and then the steam is directed to the low-pressure stage of the steam turbine, where it expands (point E to F). The exhausted steam then condenses in the condenser. It is at a pressure well below atmospheric (absolute pressure of 0.008 MPa) and is in a partially condensed state (point F), typically of a quality near 90%.

In this case, steam generators, steam turbines, condensers, and feedwater pumps constitute a heat engine subject to the efficiency limitations imposed by the second law of thermodynamics. In an ideal case (no friction, reversible processes, perfect design), this heat engine would have a Carnot efficiency of

= 1 – Tcold/Thot = 1 – 315/549 = 42.6%

where the temperature of the hot reservoir is 275.6°C (548.7K), the temperature of the cold reservoir is 41.5°C (314.7K). But the nuclear power plant is the real heat engine, in which thermodynamic processes are somehow irreversible. They are not done infinitely slowly. In real devices (turbines, pumps, and compressors), mechanical friction and heat losses cause further efficiency losses.

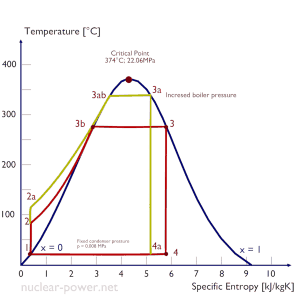

To calculate the thermal efficiency of the simplest Rankine cycle (without reheating), engineers use the first law of thermodynamics in terms of enthalpy rather than in terms of internal energy.

The first law in terms of enthalpy is:

dH = dQ + Vdp

In this equation, the term Vdp is a flow process work. This work, Vdp, is used for open flow systems like a turbine or a pump in which there is a “dp”, i.e., change in pressure. There are no changes in the control volume. As can be seen, this form of the law simplifies the description of energy transfer. At constant pressure, the enthalpy change equals the energy transferred from the environment through heating:

Isobaric process (Vdp = 0):

dH = dQ → Q = H2 – H1

At constant entropy, i.e., in isentropic process, the enthalpy change equals the flow process work done on or by the system:

Isentropic process (dQ = 0):

dH = Vdp → W = H2 – H1

It will be very useful in analyzing both thermodynamic cycles used in power engineering, i.e., in the Brayton and Rankine cycles.

The enthalpy can be made into an intensive or specific variable by dividing by the mass. Engineers use the specific enthalpy in thermodynamic analysis more than the enthalpy itself. It is tabulated in the steam tables along with specific volume and specific internal energy. The thermal efficiency of such a simple Rankine cycle and in terms of specific enthalpies would be:

It is a very simple equation, and for the determination of the thermal efficiency, you can use data from steam tables.

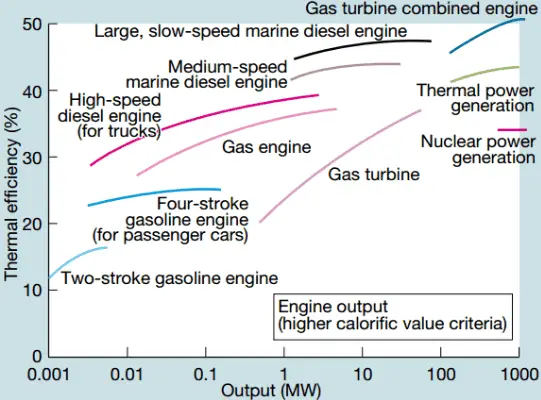

In modern nuclear power plants, the overall thermal efficiency is about one-third (33%), so 3000 MWth of thermal power from the fission reaction is needed to generate 1000 MWe of electrical power. The reason lies in relatively low steam temperature (6 MPa; 275.6°C). Higher efficiencies can be attained by increasing the temperature of the steam. But this requires an increase in pressures inside boilers or steam generators. However, metallurgical considerations place upper limits on such pressures. In comparison to other energy sources, the thermal efficiency of 33% is not much. But it must be noted that nuclear power plants are much more complex than fossil fuel power plants, and it is much easier to burn fossil fuel than to generate energy from nuclear fuel. Sub-critical fossil fuel power plants operated under critical pressure (i.e., lower than 22.1 MPa) can achieve 36–40% efficiency.

Causes of Inefficiency

As was discussed, an efficiency can range between 0 and 1. Each heat engine is somehow inefficient. This inefficiency can be attributed to three causes.

- Irreversibility of Processes. There is an overall theoretical upper limit to the efficiency of conversion of heat to work in any heat engine. This upper limit is called the Carnot efficiency. According to the Carnot principle, no engine can be more efficient than a reversible engine (Carnot heat engine) operating between the same high temperature and low-temperature reservoirs. For example, when the hot reservoir has Thot of 400°C (673K) and Tcold of about 20°C (293K), the maximum (ideal) efficiency will be: = 1 – Tcold/Thot = 1 – 293/673 = 56%. But all real thermodynamic processes are somehow irreversible. They are not done infinitely slowly. Therefore, heat engines must have lower efficiencies than limits on their efficiency due to the inherent irreversibility of the heat engine cycle they use.

- Presence of Friction and Heat Losses. In real thermodynamic systems or real heat engines, a part of the overall cycle inefficiency is due to the losses by the individual components. In real devices (such as turbines, pumps, and compressors), mechanical friction, heat losses, and losses in the combustion process cause further efficiency losses.

- Design Inefficiency. Finally, the last and important source of inefficiencies is the compromises made by engineers when designing a heat engine (e.g.,, power plant). They must consider cost and other factors in the design and operation of the cycle. As an example, consider the design of the condenser in the thermal power plants. Ideally, the steam exhausted into the condenser would have no subcooling. But real condensers are designed to subcool the liquid by a few degrees Celsius to avoid the suction cavitation in the condensate pumps. But, this subcooling increases the inefficiency of the cycle because more energy is needed to reheat the water.

Thermal Efficiency Improvement – Rankine Cycle

There are several methods, how can be the thermal efficiency of the Rankine cycle improved. Assuming that the maximum temperature is limited by the pressure inside the reactor pressure vessel, these methods are:

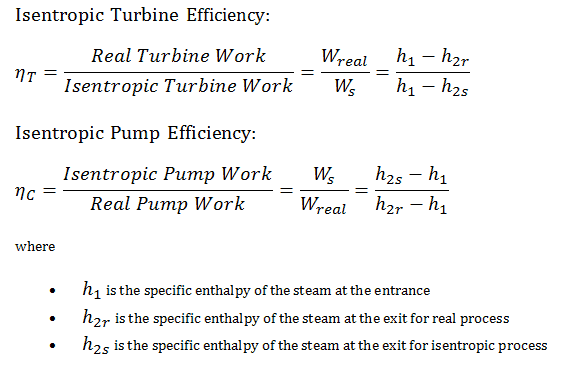

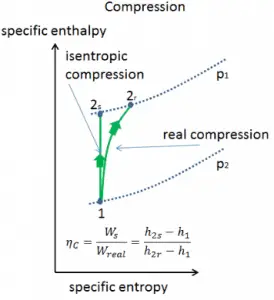

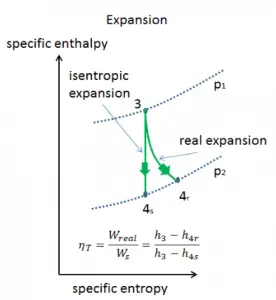

Isentropic Efficiency – Turbine, Pump

In previous chapters, we assumed that the steam expansion is isentropic, and therefore we used T4, is as the gas’s outlet temperature. These assumptions are only applicable with ideal cycles.

Most steady-flow devices (turbines, compressors, nozzles) operate under adiabatic conditions, but they are not truly isentropic but are rather idealized as isentropic for calculation purposes. We define parameters ηT, ηP, ηN as a ratio of real work done by the device to work by the device when operated under isentropic conditions (in the case of the turbine). This ratio is known as the Isentropic Turbine/Pump/Nozzle Efficiency. These parameters describe how efficiently a turbine, compressor, or nozzle approximates a corresponding isentropic device. This parameter reduces the overall efficiency and work output. For turbines, the value of ηT is typically 0.7 to 0.9 (70–90%).

See also: Isentropic Process.

Rankine Cycle – Problem with Solution

Let us assume the Rankine cycle, one of the most common thermodynamic cycles in thermal power plants. In this case, assume a simple cycle without reheat and condensing steam turbine running on saturated steam (dry steam). In this case, the turbine operates at a steady state with inlet conditions of 6 MPa, t = 275.6°C, x = 1 (point 3). Steam leaves this turbine stage at a pressure of 0.008 MPa, 41.5°C, and x = ??? (point 4).

Let us assume the Rankine cycle, one of the most common thermodynamic cycles in thermal power plants. In this case, assume a simple cycle without reheat and condensing steam turbine running on saturated steam (dry steam). In this case, the turbine operates at a steady state with inlet conditions of 6 MPa, t = 275.6°C, x = 1 (point 3). Steam leaves this turbine stage at a pressure of 0.008 MPa, 41.5°C, and x = ??? (point 4).

Calculate:

- the vapor quality of the outlet steam

- the enthalpy difference between these two states (3 → 4) corresponds to the work done by the steam, WT.

- the enthalpy difference between these two states (1 → 2) corresponds to the work done by pumps, WP.

- the enthalpy difference between these two states (2 → 3), which corresponds to the net heat added in the steam generator

- the thermodynamic efficiency of this cycle and compare this value with Carnot’s efficiency

1)

Since we do not know the exact vapor quality of the outlet steam, we have to determine this parameter. State 4 is fixed by the pressure p4 = 0.008 MPa and the fact that the specific entropy is constant for the isentropic expansion (s3 = s4 = 5.89 kJ/kgK for 6 MPa). The specific entropy of saturated liquid water (x=0) and dry steam (x=1) can be picked from steam tables. In the case of wet steam, the actual entropy can be calculated with the vapor quality, x, and the specific entropies of saturated liquid water and dry steam:

s4 = sv x + (1 – x ) sl

where

s4 = entropy of wet steam (J/kg K) = 5.89 kJ/kgK

sv = entropy of “dry” steam (J/kg K) = 8.227 kJ/kgK (for 0.008 MPa)

sl = entropy of saturated liquid water (J/kg K) = 0.592 kJ/kgK (for 0.008 MPa)

From this equation the vapor quality is:

x4 = (s4 – sl) / (sv – sl) = (5.89 – 0.592) / (8.227 – 0.592) = 0.694 = 69.4%

2)

The enthalpy for the state 3 can be picked directly from steam tables, whereas the enthalpy for the state 4 must be calculated using vapor quality:

h3, v = 2785 kJ/kg

h4, wet = h4,v x + (1 – x ) h4,l = 2576 . 0.694 + (1 – 0.694) . 174 = 1787 + 53.2 = 1840 kJ/kg

Then the work done by the steam, WT, is

WT = Δh = 945 kJ/kg

3)

Enthalpy for state 1 can be picked directly from steam tables:

h1, l = 174 kJ/kg

State 2 is fixed by the pressure p2 = 6.0 MPa and the fact that the specific entropy is constant for the isentropic compression (s1 = s2 = 0.592 kJ/kgK for 0.008 MPa). For this entropy s2 = 0.592 kJ/kgK and p2 = 6.0 MPa we find h2, subcooled in steam tables for compressed water (using interpolation between two states).

h2, subcooled = 179.7 kJ/kg

Then the work done by the pumps, WP, is

WP = Δh = 5.7 kJ/kg

4)

The enthalpy difference between (2 → 3), which corresponds to the net heat added in the steam generator, is simply:

Qadd = h3, v – h2, subcooled = 2785 – 179.7 = 2605.3 kJ/kg

Note that there is no heat regeneration in this cycle. On the other hand, most of the heat added is for the enthalpy of vaporization (i.e., for the phase change).

5)

In this case, steam generators, steam turbines, condensers, and feedwater pumps constitute a heat engine subject to the efficiency limitations imposed by the second law of thermodynamics. In the ideal case (no friction, reversible processes, perfect design), this heat engine would have a Carnot efficiency of

ηCarnot = 1 – Tcold/Thot = 1 – 315/549 = 42.6%

where the temperature of the hot reservoir is 275.6°C (548.7 K), the temperature of the cold reservoir is 41.5°C (314.7K).

The thermodynamic efficiency of this cycle can be calculated by the following formula:

thus

ηth = (945 – 5.7) / 2605.3 = 0.361 = 36.1%