Barn – Unit of Cross-section

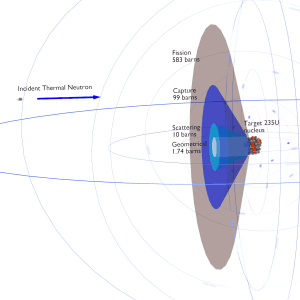

The cross-section is typically denoted σ and measured in units of the area [m2]. But a square meter (or centimeter) is tremendously large compared to the effective area of a nucleus. It has been suggested that a physicist once referred to the measure of a square meter as being “as big as a barn” when applied to nuclear processes. The name has persisted, and microscopic cross-sections are expressed in terms of barns. The standard unit for measuring a nuclear cross-section is the barn, equal to 10−28 m² or 10−24 cm². It can be seen the concept of a nuclear cross-section can be quantified physically in terms of “characteristic target area”, where a larger area means a larger probability of interaction.

Typical Values of Microscopic Cross-sections

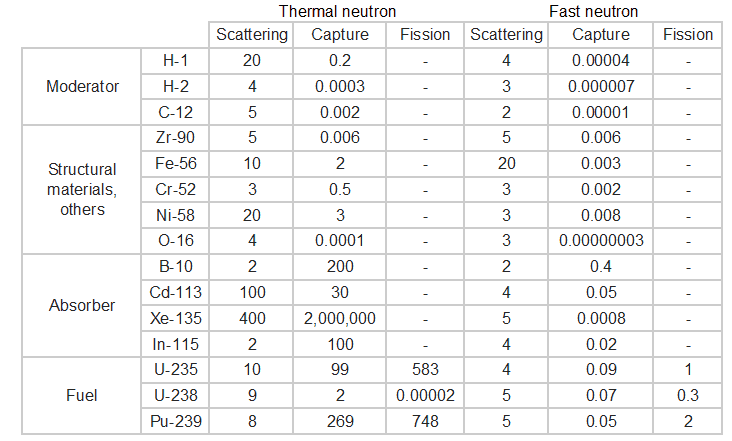

- Uranium 235 is a fissile isotope, and its fission cross-section for thermal neutrons is about 585 barns (for 0.0253 eV neutron). For fast neutrons, its fission cross-section is on the order of barns.

- Xenon-135 is a product of U-235 fission and has a very large neutron capture cross-section (about 2.6 x 106 barns).

- Boron is commonly used as a neutron absorber due to the high neutron cross-section of isotope 10B. Its (n,alpha) reaction cross-section for thermal neutrons is about 3840 barns (for 0.025 eV neutron).

- Gadolinium is commonly used as a neutron absorber due to the very high neutron absorption cross-section of two isotopes 155Gd and 157Gd. 155Gd has 61 000 barns for thermal neutrons (for 0.025 eV neutron) and 157Gd has even 254 000 barns.

See also: JANIS (Java-based Nuclear Data Information Software)

Theory of Microscopic Cross-section

The extent to which neutrons interact with nuclei is described in terms of quantities known as cross-sections. Cross-sections are used to express the likelihood of particular interaction between an incident neutron and a target nucleus. It must be noted this likelihood does not depend on real target dimensions. In conjunction with the neutron flux, it enables the calculation of the reaction rate, for example, to derive the thermal power of a nuclear power plant. The standard unit for measuring the microscopic cross-section (σ-sigma) is the barn, equal to 10-28 m2. This unit is very small. Therefore barns (abbreviated as “b”) are commonly used.

The cross-section σ can be interpreted as the effective ‘target area’ that a nucleus interacts with an incident neutron. The larger the effective area, the greater the probability of reaction. This cross-section is usually known as the microscopic cross-section.

The concept of the microscopic cross-section is therefore introduced to represent the probability of a neutron-nucleus reaction. Suppose that a thin ‘film’ of atoms (one atomic layer thick) with Na atoms/cm2 is placed in a monodirectional beam of intensity I0. Then the number of interactions C per cm2 per second will be proportional to the intensity I0 and the atom density Na. We define the proportionality factor as the microscopic cross-section σ:

σt = C/Na.I0

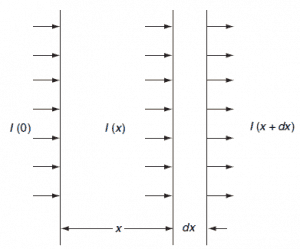

To be able to determine the microscopic cross-section, transmission measurements are performed on plates of materials. Assume that if a neutron collides with a nucleus, it will either be scattered into a different direction or be absorbed (without fission absorption). Assume that N (nuclei/cm3) of the material will then be N.dx per cm2 in the layer dx.

Only the neutrons that have not interacted will remain traveling in the x-direction. This causes the intensity of the un-collided beam will be attenuated as it penetrates deeper into the material.

Then, according to the definition of the microscopic cross-section, the reaction rate per unit area is Nσ Ι(x)dx. This is equal to the decrease of the beam intensity, so that:

-dI = N.σ.Ι(x).dx

and

Ι(x) = Ι0e-N.σ.x

It can be seen that whether a neutron will interact with a certain volume of material depends not only on the microscopic cross-section of the individual nuclei but also on the density of nuclei within that volume. It depends on the N.σ factor. This factor is therefore widely defined, and it is known as the macroscopic cross-section.

The difference between the microscopic and macroscopic cross-sections is extremely important. The microscopic cross-section represents the effective target area of a single nucleus. In contrast, the macroscopic cross-section represents the effective target area of all of the nuclei contained in a certain volume.

Microscopic cross-sections constitute key parameters of nuclear fuel. In general, neutron cross-sections are essential for reactor core calculations and part of data libraries, such as ENDF/B-VII.1.

The neutron cross-section is variable and depends on:

Target nucleus (hydrogen, boron, uranium, etc.). Each isotope has its own set of cross-sections.

Target nucleus (hydrogen, boron, uranium, etc.). Each isotope has its own set of cross-sections.- Type of the reaction (capture, fission, etc.). Cross-sections are different for each nuclear reaction.

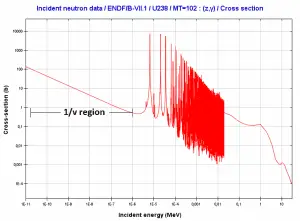

- Neutron energy (thermal neutron, resonance neutron, fast neutron). For a given target and reaction type, the cross-section is strongly dependent on the neutron energy. In the common case, the cross-section is usually much larger at low energies than at high energies. This is why most nuclear reactors use a neutron moderator to reduce the neutron’s energy and thus increase the probability of fission, essential to produce energy and sustain the chain reaction.

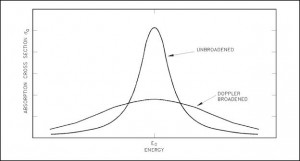

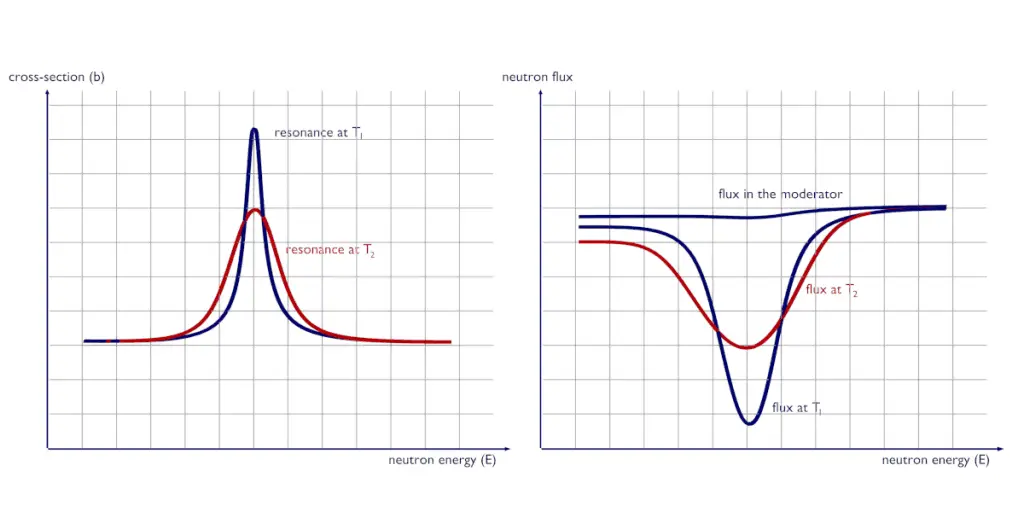

- Target energy (temperature of target material – Doppler broadening). This dependency is not so significant, but the target energy strongly influences the inherent safety of nuclear reactors due to a Doppler broadening of resonances.

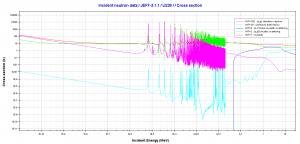

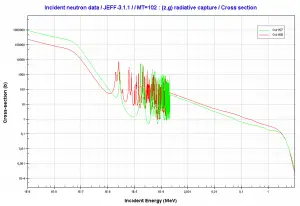

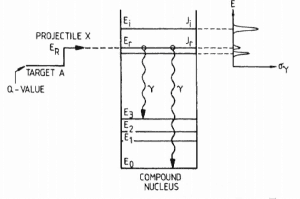

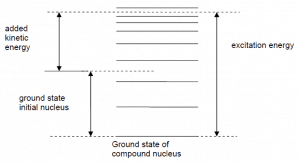

Microscopic cross-section varies with incident neutron energy. Some nuclear reactions exhibit very specific dependency on incident neutron energy. This dependency will be described in the example of the radiative capture reaction. The radiative capture cross-section represents the likelihood of a neutron radiative capture as σγ. The following dependency is typical for radiative capture. It definitely does not mean that it is typical for other types of reactions (see elastic scattering cross-section or (n, alpha) reaction cross-section).

The capture cross-section can be divided into three regions according to the incident neutron energy. These regions will be discussed separately.

- 1/v Region

- Resonance Region

- Fast Neutrons Region

Doppler Broadening of Resonances

In general, Doppler broadening is the broadening of spectral lines due to the Doppler effect caused by a distribution of kinetic energies of molecules or atoms. In reactor physics, a particular case of this phenomenon is the thermal Doppler broadening of the resonance capture cross-sections of the fertile material (e.g.,, 238U or 240Pu) caused by the thermal motion of target nuclei in the nuclear fuel.

The Doppler broadening of resonances is an important phenomenon that improves reactor stability because it accounts for the dominant part of the fuel temperature coefficient (the change in reactivity per degree change in fuel temperature) in thermal reactors and makes a substantial contribution in fast reactors as well. This coefficient is also called the prompt temperature coefficient because it causes an immediate response to changes in fuel temperature. The prompt temperature coefficient of most thermal reactors is negative.

See also: Doppler Broadening.

Self-Shielding

It was written, in some cases, the amount of absorption reactions is dramatically reduced despite the unchanged microscopic cross-section of the material. This phenomenon is commonly known as the resonance self-shielding and also contributes to reactor stability. There are two types of self-shielding.

- Energy Self-shielding.

- Spatial Self-shielding.

See also: Resonance Self-shielding An increase in temperature from T1 to T2 causes the broadening of spectral lines of resonances. Although the area under the resonance remains the same, the broadening of spectral lines causes an increase in neutron flux in the fuel φf(E), increasing the absorption as the temperature increases.

An increase in temperature from T1 to T2 causes the broadening of spectral lines of resonances. Although the area under the resonance remains the same, the broadening of spectral lines causes an increase in neutron flux in the fuel φf(E), increasing the absorption as the temperature increases.