Nuclear Fuel

Nuclear fuel is generally any material that can be ‘burned’ by nuclear fission or fusion to derive nuclear energy. There are many design considerations for the material composition and geometric configuration of the various components comprising a nuclear fuel system. Common nuclear reactors use enriched uranium and plutonium as fuel.

Generally, there are two types of nuclear fuel cycles (for PWRs):

- Uranium fuel cycle. Uses an enriched uranium fuel (~4% of U-235) as a fresh fuel. During the fuel burning, the content of the U-235 decreases, and the content of the plutonium increases (up to ~1% of Pu ).

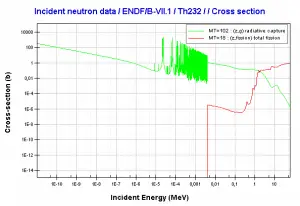

- Thorium fuel cycle. Uses a thorium – 232 as a fertile material. During the fuel burning, the Th-232 transforms into a fissile U-233.

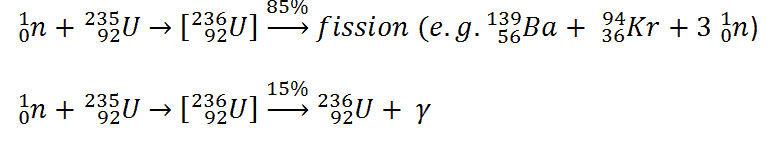

Typically, when uranium 235 nucleus undergoes fission, the nucleus splits into two smaller nuclei (triple fission can also rarely occur), along with a few neutrons (the average is 2.43 neutrons per fission by thermal neutron) and release of energy in the form of heat and gamma rays. The average of the fragment atomic mass is about 118, but very few fragments near that average are found. It is much more probable to break up into unequal fragments, and the most probable fragment masses are around mass 95 (Krypton) and 137 (Barium). Most fission fragments are highly unstable(radioactive) nuclei and undergo further radioactive decays to stabilize themselves.

Energy Release per Fission

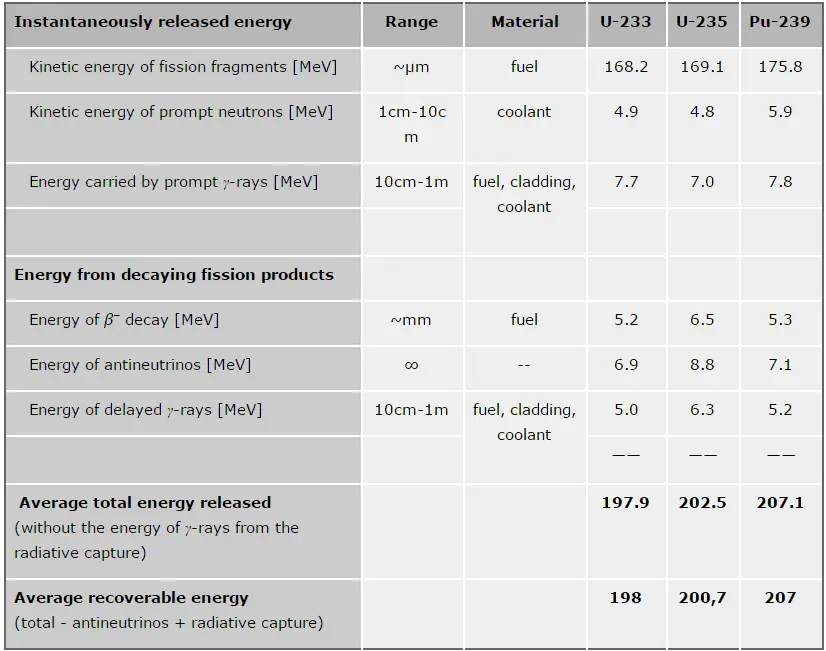

In general, nuclear fission results in the release of enormous quantities of energy. The amount of energy depends strongly on the nucleus fissioned and depends strongly on an incident neutron's kinetic energy. It is necessary to precisely identify the individual components of this energy to calculate the reactor's power. At first, it is important to distinguish between the total energy released and the energy that can be recovered in a reactor.

In general, nuclear fission results in the release of enormous quantities of energy. The amount of energy depends strongly on the nucleus fissioned and depends strongly on an incident neutron's kinetic energy. It is necessary to precisely identify the individual components of this energy to calculate the reactor's power. At first, it is important to distinguish between the total energy released and the energy that can be recovered in a reactor.

The total energy released in fission can be calculated from binding energies of the initial target nucleus to be fissioned and binding energies of fission products. But not all the total energy can be recovered in a reactor. For example, about 10 MeV is released in the form of neutrinos (in fact, antineutrinos). Since the neutrinos are weakly interacting (with an extremely low cross-section of any interaction), they do not contribute to the energy that the reactor can recover.

See also: Energy Release from Fission.

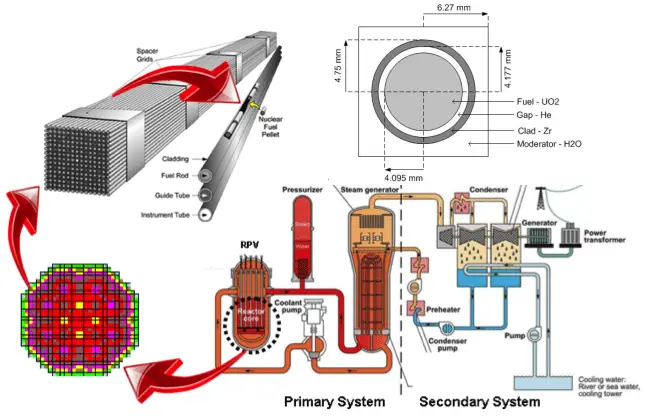

PWR nuclear fuel assembly

Source: www.kernbrennstoff.de

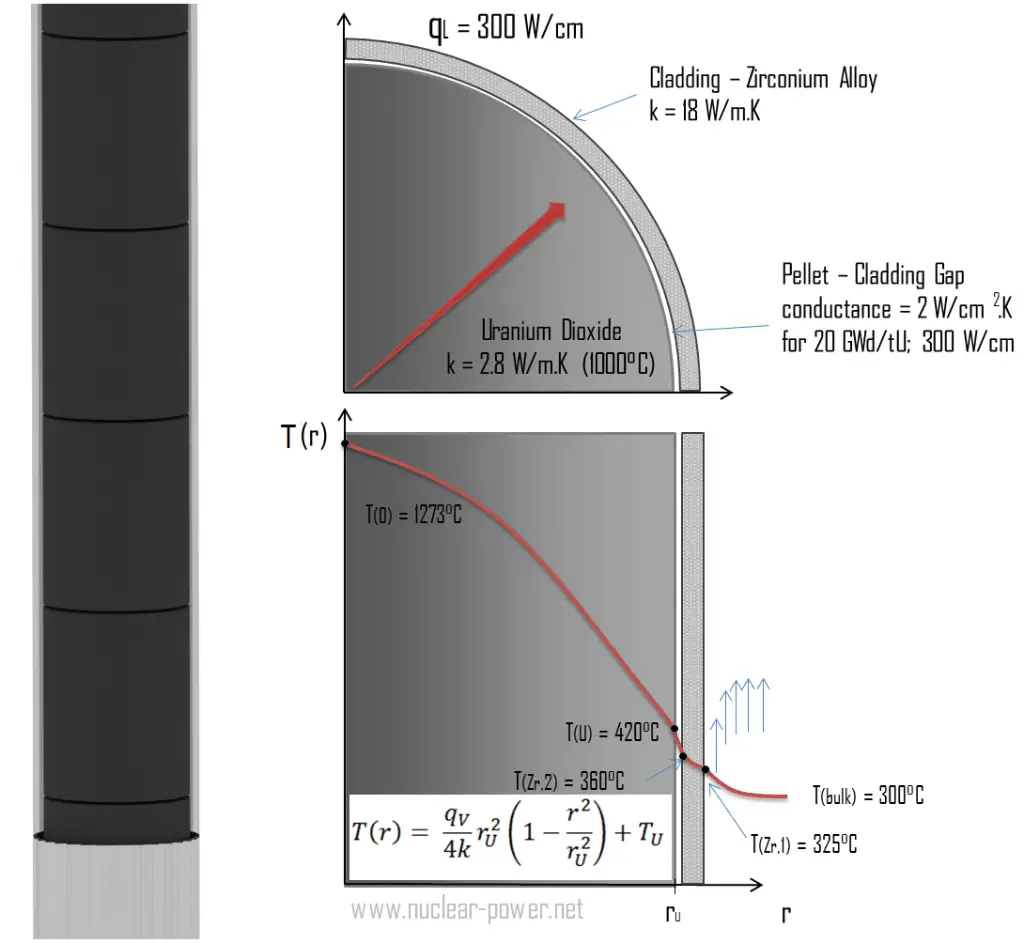

Pressurized water reactors (PWRs) are the most common type of nuclear reactor, accounting for two-thirds of current installed nuclear generating capacity worldwide. Most of PWRs use uranium fuel, which is in the form of uranium dioxide. Uranium dioxide is a black semiconducting solid with very low thermal conductivity. On the other hand, uranium dioxide has a very high melting point and has well-known behavior. The UO2 is pressed into pellets. These pellets are then sintered into the solid.

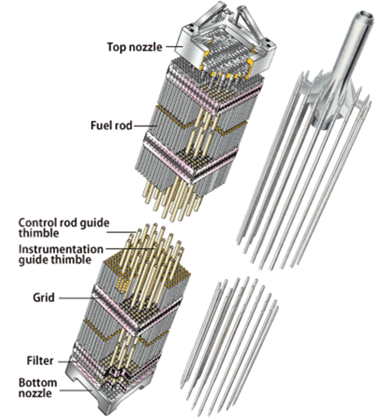

These pellets are then loaded and encapsulated within a fuel rod (or fuel pin) made of zirconium alloys due to its very low absorption cross-section (unlike the stainless steel). The surface of the tube, which covers the pellets, is called fuel cladding. Fuel rods are the base element of a fuel assembly. The fuel rods and the pellets constitute the first barrier in Defence in-depth strategy. The first barrier, which retains radioactive material within the fuel and protects the environment.

The collection of fuel rods or elements is called the fuel assembly. The fuel assembly constitutes the base element of the nuclear reactor core. The reactor core (PWR type) contains about 157 fuel assemblies (depending on a reactor type). Western PWRs use a square lattice arrangement, and assemblies are characterized by the number of rods they contain, typically 17×17 in current designs. The enrichment of fuel rods is never uniformed. The enrichment is differentiated in the radial direction but also axial direction. This arrangement improves power distribution and improves fuel economy.

Russian VVER-type reactors use a fuel characterized by their hexagonal arrangement but otherwise similar to other PWR fuel assemblies.

A PWR fuel assemblies stand between four and five meters high, are about 20 cm across, and weighs about half a tonne. The assemblies have vacant rod positions for control rods or in-core instrumentation. Into a vacant tube called the guide thimble can be vertically inserted control rods, in-core instrumentation, neutron source, or a test segment.

Source: www.world-nuclear.org

A PWR fuel assembly comprises a bottom nozzle into which rods are fixed through the lattice. A top nozzle ends the whole assembly as the whole. There are spacing grids between these nozzles. These grids ensure an exact guiding of the fuel rods. The bottom and top nozzles are heavily constructed as they provide much of the mechanical support for the fuel assembly structure.

An 1100 MWe (3300 MWth) nuclear core may contain 157 fuel assemblies composed of over 45,000 fuel rods and 15 million fuel pellets. Generally, a common fuel assembly contains energy for approximately 4 years of operation at full power. Once loaded, the fuel stays in the core for 4 years, depending on the design of the operating cycle. During these 4 years, the reactor core has to be refueled. During refueling, every 12 to 18 months, some of the fuel - usually one-third or one-quarter of the core – is removed to the spent fuel pool. At the same time, the remainder is rearranged to a location in the core better suited to its remaining level of enrichment. The removed fuel (one-third or one-quarter of the core, i.e., 40 assemblies) has to be replaced by new fuel assemblies.

Typical PWR fuel assembly consists of:

- Fuel rods. Fuel rods contain fuel and burnable poisons.

- Top nozzle. Provides the mechanical support for the fuel assembly structure.

- Bottom nozzle. Provides the mechanical support for the fuel assembly structure.

- Spacing grid. Ensures an exact guiding of the fuel rods.

- Guide thimble tube. Vacant tube for control rods or in-core instrumentation.

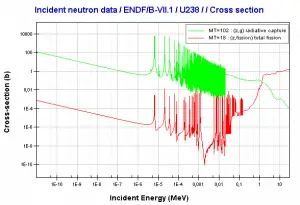

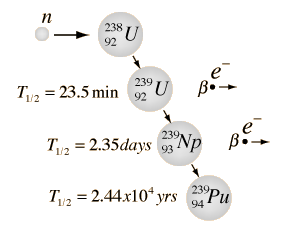

Nuclear Fuel Breeding

All commercial light water reactors contain both fissile and fertile materials. For example, most PWRs use low enriched uranium fuel with enrichment of 235U up to 5%. Therefore more than 95% of the content of fresh fuel is fertile isotope 238U. During fuel burnup, the fertile materials (conversion of 238U to fissile 239Pu known as fuel breeding) partially replace fissile 235U, thus permitting the power reactor to operate longer before the amount of fissile material decreases to the point where reactor criticality is no longer manageable.

The fuel breeding in the fuel cycle of all commercial light water reactors plays a significant role. In recent years, the commercial power industry has emphasized high-burnup fuels (up to 60 – 70 GWd/tU), typically enriched to higher percentages of 235U (up to 5%). As burnup increases, a higher percentage of the total power produced in a reactor is due to the fuel bred inside the reactor.

At a burnup of 30 GWd/tU (gigawatt-days per metric ton of uranium), about 30% of the total energy released comes from bred plutonium. At 40 GWd/tU, that percentage increases to about forty percent. This corresponds to a breeding ratio for these reactors of about 0.4 to 0.5. That means about half of the fissile fuel in these reactors is bred there. This effect extends the cycle length for such fuels to sometimes nearly twice what it would be otherwise. MOX fuel has a smaller breeding effect than 235U fuel and is thus more challenging and slightly less economical to use due to a quicker drop-off in reactivity through cycle life.

Comparison of cross-sections

Source: JANIS (Java-based nuclear information software) http://www.oecd-nea.org/janis/

http://www.oecd-nea.org/janis/

Uranium 238. Comparison of total fission cross-section and cross-section for radiative capture.

http://www.oecd-nea.org/janis/

Thorium 232. Comparison of total fission cross-section and cross-section for radiative capture.

Fuel Consumption - Summary

Consumption of a 3000MWth (~1000MWe) reactor (12-months fuel cycle)

It is an illustrative example, and the following data do not correspond to any reactor design.

- A typical reactor may contain about 165 tonnes of fuel (including structural material).

- A typical reactor may contain about 100 tonnes of enriched uranium (i.e., about 113 tonnes of uranium dioxide).

- This fuel is loaded within, for example, 157 fuel assemblies composed of over 45,000 fuel rods.

- A common fuel assembly contains energy for approximately 4 years of operation at full power.

- Therefore about one-quarter of the core is yearly removed to the spent fuel pool (i.e., about 40 fuel assemblies). At the same time, the remainder is rearranged to a location in the core better suited to its remaining level of enrichment (see Power Distribution).

- The removed fuel (spent nuclear fuel) still contains about 96% of reusable material (it must be removed due to decreasing kinf of an assembly).

- This reactor's annual natural uranium consumption is about 250 tons of natural uranium (to produce about 25 tons of enriched uranium).

- The annual enriched uranium consumption of this reactor is about 25 tonnes of enriched uranium.

- The annual fissile material consumption of this reactor is about 1 005 kg.

- The annual matter consumption of this reactor is about 1.051 kg.

- But it corresponds to about 3 200 000 tons of coal burned in coal-fired power plants per year.

See also: Fuel Consumption

Uranium vs. MOX Fuel - Neutron Flux Difference

Note that there is a difference between neutron fluxes in the uranium fueled core and the MOX fueled core. The average neutron flux in the first example, in which the neutron flux in a uranium-loaded reactor core was calculated, was 3.11 x 1013 neutrons.cm-2.s-1. Compared to this value, the average neutron flux in 100% MOX fueled core is about 2.6 times lower (1.2 x 1013 neutrons.cm-2.s-1), while the reaction rate remains almost the same. This fact is of importance in the reactor core design and the design of reactivity control. It is primarily caused by:

- Higher fission cross-section of 239Pu. The fission cross-section is about 750 barns in comparison with 585 barns for 235U.

- Higher energy release per one fission event. A MOX core does not require such neutron flux as uranium fueled core to generate the same amount of energy.

- Larger fissile loading. The main reason is the larger fissile loading. In MOX fuels, there is a relatively high buildup of 240Pu and 242Pu. Due to the relatively lower fission-to-capture ratio, there is a higher accumulation of these isotopes, parasitic absorbers, resulting in a reactivity penalty. In general, the average regeneration factor η is lower for 239Pu fuel than for 235U fuel. Therefore the MOX fuel requires a larger fissile loading to achieve the same initial excess of reactivity at the beginning of the fuel cycle.

The relatively lower average neutron flux in MOX cores has the following consequences on reactor core design:

- Because of the lower neutron flux and the larger thermal absorption cross-section for 239Pu, reactivity worth of control rods, chemical shim (PWRs), and burnable absorbers is less with MOX fuel.

- The high fission cross-section of 239Pu and the lower neutron flux lead to greater power peaking in fuel rods that are located near water gaps or when MOX fuel is loaded with uranium fuel together.

Accident Tolerant Fuels

Accident tolerant fuels (ATF) are a series of new nuclear fuel concepts researched to improve fuel performance during normal operation, transient conditions, and accident scenarios, such as loss-of-coolant accident (LOCA) or reactivity-initiated accidents (RIA). A review of fuel behavior was initiated following the Fukushima Daiichi accident. Zirconium alloy clad fuel operates successfully to high burnup and results from 40 years of continuous development and improvement. However, under severe accident conditions, the high-temperature zirconium–steam interaction can be a major source of damage to the power plant.

These upgrades include:

- specially designed additives to standard fuel pellets intended to improve various properties and performance

- robust coatings applied to the outside of standard claddings intended to reduce corrosion, increase wear resistance, and reduce the production of hydrogen under high-temperature (accident) conditions

- development of completely new fuel designs with ceramic cladding and different fuel materials

Types of Accident Tolerant Fuels

Advanced Fuel Clad

While current nuclear fuel designs have operated well under normal plant conditions, existing nuclear fuel designs can be challenged when put under beyond-design-basis severe-accident scenarios. In the event of such conditions, the long-term loss of coolant and the resulting high temperatures of the fuel can lead to the degradation of the fuel cladding and the early release of fission products.

Proposed ATF concepts seek to reduce severe accident (SA) risks by increasing the coping time available to operators for accident response, reducing the extent and rate of heat and hydrogen production from high-temperature (HT) steam oxidation, or reducing severe accident consequences by enhancing fission product (FP) retention. The desired attributes for a practical ATF cladding material are quite rigorous. In addition to good material properties at high temperature, the candidate material must be compatible with current fuel/core designs and provide economical operation, including good neutronics. Moreover, it must be highly reliable, corrosion-resistant, and exhibit low embrittlement at high burnups from an operational perspective.

According to the NEA report, five different classes of cladding designs were the object of the review:

- Coated and improved Zr-alloys,

- Advanced steels,

- Refractory metals,

- SiC and SiC/SiC-composite claddings

- non-fuel components such as SiC/SiC channel boxes or accident-tolerant control rods (ATCR).

Advanced Fuel Pellets

According to the NEA report, the fuel designs covered by the Task Force on Advanced Fuel Designs consist of three different concepts:

- Improved UO2 fuel. Regarding the improved UO2 fuel, this particular design was divided into two sub-concepts, such as oxide-doped UO2 and high-thermal conductivity UO2 (designed by adding metallic or ceramic dopant).

- High-density fuel.

- Encapsulated fuel (TRISO-SiC-composite pellets).