Many of the heat transfer processes encountered in the industry involve composite systems and even involve a combination of both conduction and convection. It is often convenient to work with an overall heat transfer coefficient, known as a U-factor with these composite systems. The U-factor is defined by an expression analogous to Newton’s law of cooling:

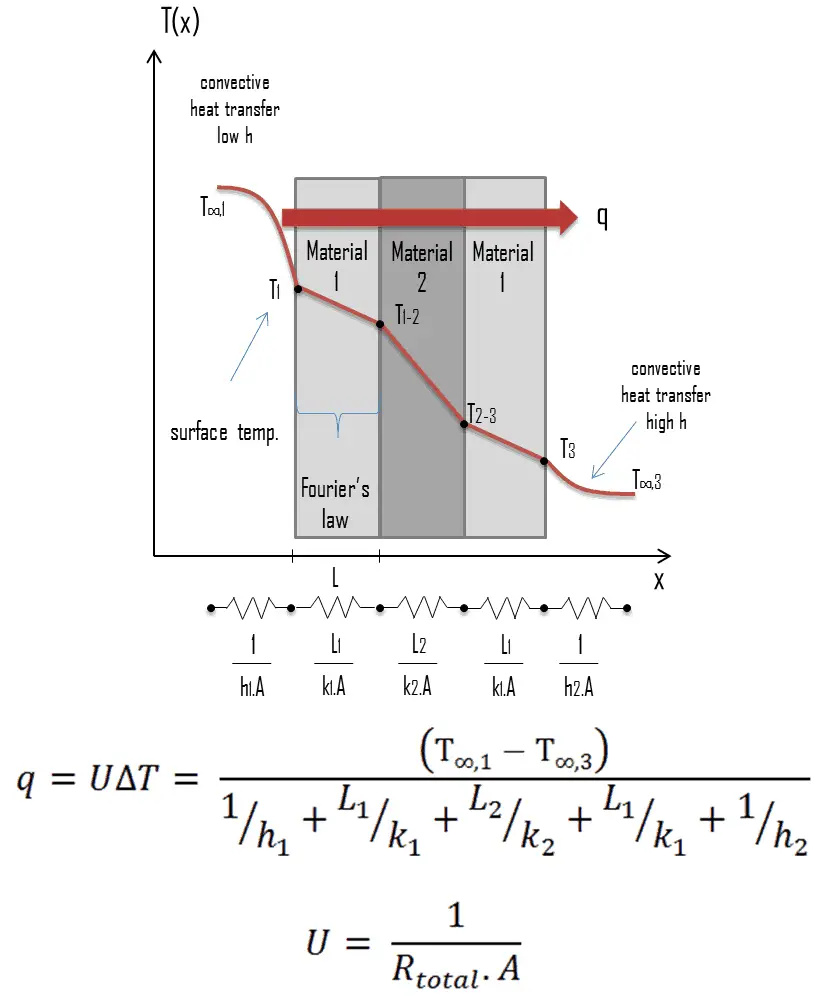

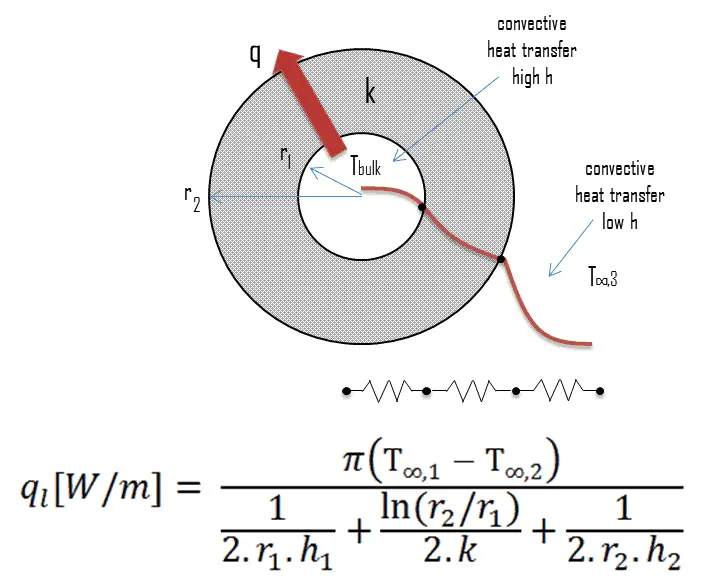

The overall heat transfer coefficient is related to the total thermal resistance and depends on the geometry of the problem. For example, heat transfer in a steam generator involves convection from the bulk of the reactor coolant to the steam generator inner tube surface, conduction through the tube wall, and convection (boiling) from the outer tube surface to the secondary side fluid.

In cases of combined heat transfer for a heat exchanger, there are two values for h. The convective heat transfer coefficient (h) for the fluid film inside the tubes and a convective heat transfer coefficient for the fluid film outside the tubes. The thermal conductivity (k) and thickness (Δx) of the tube wall must also be accounted for.

Overall Heat Transfer Coefficient – Plane Wall

Overall Heat Transfer Coefficient – Cylindrical Tubes

Steady heat transfer through multilayered cylindrical or spherical shells can be handled just like multilayered plane walls.

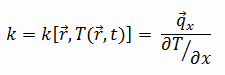

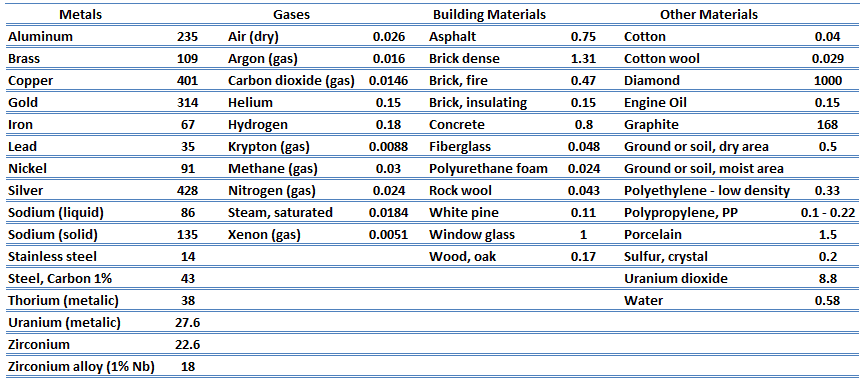

Thermal Conductivity

The heat transfer characteristics of solid material are measured by a property called the thermal conductivity, k (or λ), measured in W/m.K. It measures a substance’s ability to transfer heat through a material by conduction. Note that Fourier’s law applies to all matter, regardless of its state (solid, liquid, or gas). Therefore, it is also defined for liquids and gases.

The thermal conductivity of most liquids and solids varies with temperature, and for vapors, it also depends upon pressure. In general:

Most materials are nearly homogeneous. Therefore, we can usually write k = k (T). Similar definitions are associated with thermal conductivities in the y- and z-directions (ky, kz), but for an isotropic material, the thermal conductivity is independent of the direction of transfer, kx = ky = kz = k.

The previous equation follows that the conduction heat flux increases with increasing thermal conductivity and increases with increasing temperature differences. In general, the thermal conductivity of a solid is larger than that of a liquid, which is larger than that of a gas. This trend is due largely to differences in intermolecular spacing for the two states of matter. In particular, diamond has the highest hardness and thermal conductivity of any bulk material.

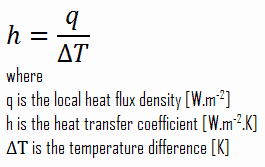

Convective Heat Transfer Coefficient

As can be seen, the constant of proportionality will be crucial in calculations, and it is known as the convective heat transfer coefficient, h. The convective heat transfer coefficient, h, can be defined as:

The rate of heat transfer between a solid surface and a fluid per unit surface area per unit temperature difference.

The convective heat transfer coefficient depends on the fluid’s physical properties and the physical situation. The convective heat transfer coefficient is not a property of the fluid. It is an experimentally determined parameter whose value depends on all the variables influencing convection, such as the surface geometry, the nature of fluid motion, the properties of the fluid, and the bulk fluid velocity.

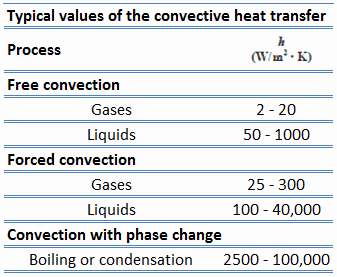

Typically, the convective heat transfer coefficient for laminar flow is relatively low compared to the convective heat transfer coefficient for turbulent flow. This is due to turbulent flow having a thinner stagnant fluid film layer on the heat transfer surface.

It must be noted this stagnant fluid film layer plays a crucial role in the convective heat transfer coefficient. It is observed that the fluid comes to a complete stop at the surface and assumes a zero velocity relative to the surface. This phenomenon is known as the no-slip condition, and therefore, at the surface, energy flow occurs purely by conduction. But in the next layers, both conduction and diffusion-mass movement occur at the molecular or macroscopic levels. Due to the mass movement, the rate of energy transfer is higher.