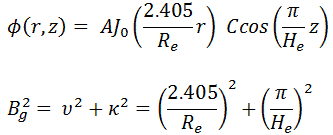

In previous chapters, we have solved diffusion equations for various shapes of reactors. For example, the solution for a finite cylindrical reactor is:

where Bg2 is the total geometrical buckling.

It must be added there are constants A and C that cannot be obtained from the diffusion equation because these constants give the absolute value of neutron flux or the reactor power.

There is a direct proportionality between the neutron flux and the reactor thermal power in each nuclear reactor. The term thermal power is usually used because it means the rate at which heat is produced in the reactor core due to fissions in the fuel. Nuclear power plants also use the total output of electrical power. Still, this value is due to the efficiency of conversion (usually from 30% to 40%) always being smaller than the reactor’s thermal power.

Back to the proportionality between the neutron flux and the reactor thermal power.

Reaction Rate

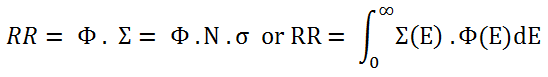

Knowledge of the neutron flux (the total path length of all the neutrons in a cubic centimeter in a second) and the macroscopic cross-sections (the probability of having an interaction per centimeter path length) allows us to compute the rate of interactions (e.g.,, rate of fission reactions). This reaction rate (the number of interactions taking place in that cubic centimeter in one second) is then given by multiplying them together:

where:

Ф – neutron flux (neutrons.cm-2.s-1)

σ – microscopic cross-section (cm2)

N – atomic number density (atoms.cm-3)

The reaction rate for various types of interactions is found from the appropriate cross-section type:

- Σt . Ф – total reaction rate

- Σa . Ф – absorption reaction rate

- Σc . Ф – radiative capture reaction rate

- Σf . Ф – fission reaction rate

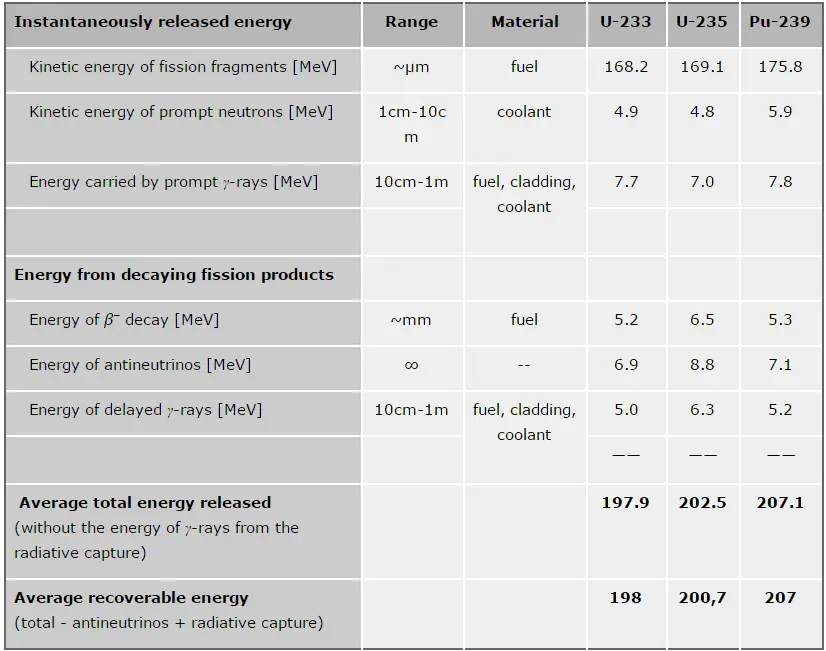

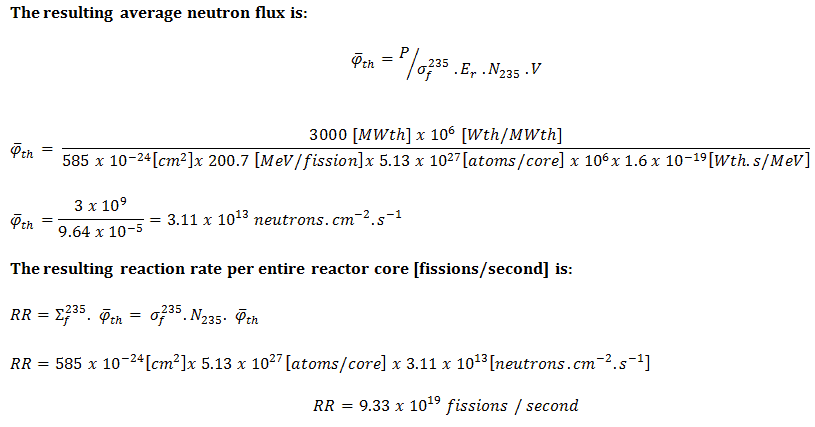

To determine the thermal power, we have to focus on the fission reaction rate. For simplicity, let assume that the fissionable material is uniformly distributed in the reactor. In this case, the macroscopic cross-sections are independent of position. Multiplying the fission reaction rate per unit volume (RR = Ф . Σ) by the total volume of the core (V) gives us the total number of reactions occurring in the reactor core per unit time. But we also know the amount of energy released per one fission reaction to be about 200 MeV/fission. Now, it is possible to determine the energy release rate (power) due to the fission reaction. The following equation gives it:

P = RR . Er . V = Ф . Σf . Er . V = Ф . NU235 . σf235 . Er . V

where:

P – reactor power (MeV.s-1)

Ф – neutron flux (neutrons.cm-2.s-1)

σ – microscopic cross section (cm2)

N – atomic number density (atoms.cm-3)

Er – the average recoverable energy per fission (MeV / fission)

V – total volume of the core (m3)

Zero Power Criticality vs. Power Operation

The neutron flux can have any value, and the critical reactor can operate at any power level. It should be noted the flux shape derived from the diffusion theory is only a hypothetical case in a uniform homogeneous cylindrical reactor at low power levels (at “zero power criticality”).

In the power reactor core at power operation, the neutron flux can reach, for example, about 3.11 x 1013 neutrons.cm-2.s-1, but this value depends significantly on many parameters (type of fuel, fuel burnup, fuel enrichment, position in fuel pattern, etc.). The power level does not influence the criticality (keff) of a power reactor unless thermal reactivity feedbacks act (operation of a power reactor without reactivity feedbacks is between 10E-8% – 1% of rated power).

At power operation (i.e., above 1% of rated power), the reactivity feedbacks cause the flattening of the flux distribution because the feedbacks acts stronger on positions where the flux is higher. The neutron flux distribution in commercial power reactors depends on many other factors such as the fuel loading pattern, control rods position, and it may also oscillate within short periods (e.g.,, due to the spatial distribution of xenon nuclei). There is no cosine and J0 in the commercial power reactor at power operation.

See also: Nuclear Reactor as the Antineutrino Source.

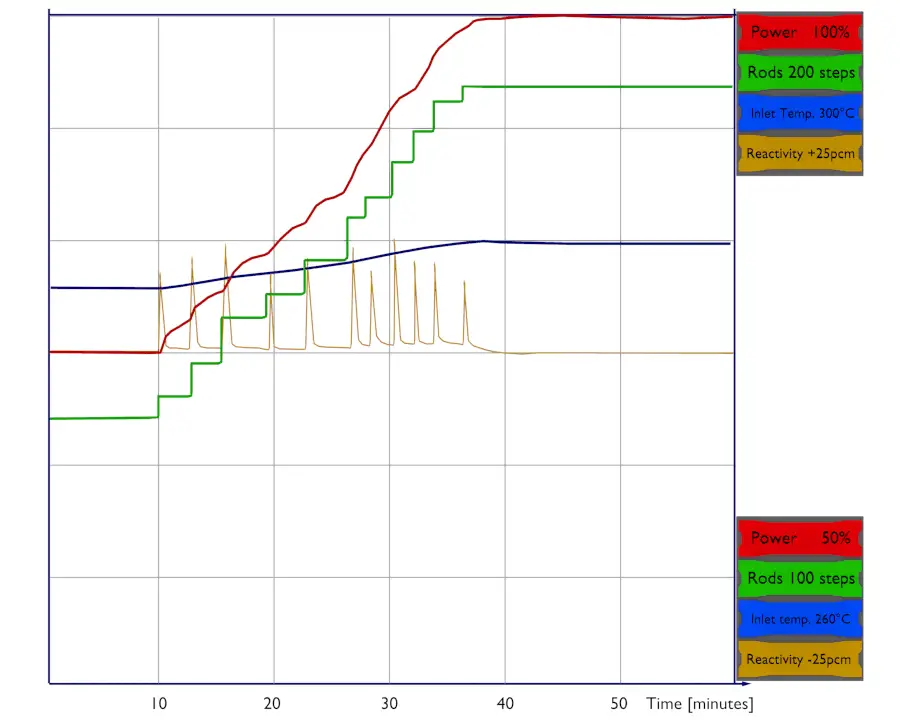

Example: Power increase – from 75% up to 100%

The temperature, pressure, or void fraction change during any power increase, and the core’s reactivity changes accordingly. It is difficult to change any operating parameter and not affect every other property of the core. Since it is difficult to separate all these effects (moderator, fuel, void, etc.), the power coefficient is defined. The power coefficient combines the Doppler, moderator temperature, and void coefficients. It is expressed as a change in reactivity per change in percent power, Δρ/Δ% power. The value of the power coefficient is always negative in core life. Still, it is more negative at the end of the cycle primarily due to the decrease in the moderator temperature coefficient.

Let us assume that the reactor is critical at 75% of rated power and that the plant operator wants to increase power to 100% of rated power. The reactor operator must first bring the reactor supercritical by inserting a positive reactivity (e.g.,, by control rod withdrawal or boron dilution). As the thermal power increases, moderator temperature and fuel temperature increase, causing a negative reactivity effect (from the power coefficient), and the reactor returns to the critical condition. Positive reactivity must be continuously inserted (via control rods or chemical shim) to keep the power to be increasing. After each reactivity insertion, the reactor power stabilizes itself proportionately to the reactivity inserted. The total amount of feedback reactivity that must be offset by control rod withdrawal or boron dilution during the power increase (from ~1% – 100%) is known as the power defect.

Let assume:

- the power coefficient: Δρ/Δ% = -20pcm/% of rated power

- differential worth of control rods: Δρ/Δstep = 10pcm/step

- worth of boric acid: -11pcm/ppm

- desired trend of power decrease: 1% per minute

75% → ↑ 20 steps or ↓ 18 ppm of boric acid within 10 minutes → 85% → next ↑ 20 steps or ↓ 18 ppm within 10 minutes → 95% → final ↑ 10 steps or ↓ 9 ppm within 5 minutes → 100%

Thermal Power and Power Distribution

The power distribution significantly changes also with changes in the thermal power of the reactor. During power changes at power operation mode (i.e., from about 1% up to 100% of rated power), the temperature reactivity effects play a very important role. As the neutron population increases, the fuel and the moderator increase their temperature, which results in a decrease in reactivity of the reactor (almost all reactors are designed to have the temperature coefficients negative). The negative reactivity coefficient acts against the initial positive reactivity insertion, and this positive reactivity is offset by negative reactivity from temperature feedbacks.

This effect naturally occurs on a global scale and also on a local scale.

During thermal power increase, the effectiveness of temperature feedbacks will be greatest where the power is greatest. This process causes the flattening of the flux distribution because the feedbacks acts stronger on positions where the flux is higher.

It must be noted, the effect of change in the thermal power has significant consequences on the axial power distribution.

In reality, when there is a change in the thermal power, and the coolant flow rate remains the same, the difference between inlet and outlet temperatures must increase. It follows from the basic energy equation of reactor coolant, which is below:

P=↓ṁ.c.↑∆t

The inlet temperature is determined by the pressure in the steam generators. Therefore the inlet temperature changes minimally during the change of thermal power. It follows the outlet temperature must change significantly as the thermal power changes. When the inlet temperature remains almost the same and the outlet changes significantly, it stands to reason, the average temperature of coolant (moderator) will also change significantly. It follows the temperature of the top half of the core increases more than the temperature of the bottom half of the core. Since the moderator temperature feedback must be negative, the power from the top half will shift to the bottom half. In short, the top half of the core is cooled (moderated) by hotter coolant, and therefore it is worse moderated. Hence the axial flux difference, defined as the difference in normalized flux signals (AFD) between the top and bottom halves of a two-section excore neutron detector, will decrease.

AFD is defined as:

AFD or ΔI = Itop – Ibottom

where Itop and Ibottom are expressed as a fraction of rated thermal power.

Types of Reactor Power

In general, we have to distinguish between three types of power outputs in power reactors.

- Nuclear Power. Since the thermal power produced by nuclear fissions is proportional to neutron flux level, the most important is a measurement of the neutron flux from the reactor safety point of view. The neutron flux is usually measured by excore neutron detectors, which belong to the so-called excore nuclear instrumentation system (NIS). The excore nuclear instrumentation system monitors the reactor’s power level by detecting neutron leakage from the reactor core. The excore nuclear instrumentation system is considered a safety system because it provides inputs to the reactor protection system during startup and power operation. This system is of the highest importance for reactor protection systems because changes in the neutron flux can be almost promptly recognized only via this system.

- Thermal Power. Although nuclear power provides a prompt response to neutron flux changes and is an irreplaceable system, it must be calibrated. The accurate thermal power of the reactor can be measured only by methods based on the energy balance of the primary circuit or the energy balance of the secondary circuit. These methods provide accurate reactor power, but these methods are insufficient for safety systems. Signal inputs to these calculations are, for example, the hot leg temperature or the flow rate through the feedwater system, and these signals change very slowly with neutron power changes.

- Electrical Power. Electric power is the rate at which the generator generates electrical energy. For example, for a typical nuclear reactor with thermal power of 3000 MWth, about ~1000MWe of electrical power is generated in the generator.