For fully developed (hydrodynamically and thermally) turbulent flow in a smooth circular tube, the local Nusselt number may be obtained from the well-known Dittus-Boelter equation.

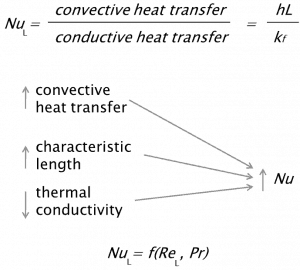

Nusselt number is equal to the dimensionless temperature gradient at the surface, and it provides a measure of the convection heat transfer occurring at the surface. The conductive component is measured under the same conditions as the heat convection but with stagnant fluid. The Nusselt number is to the thermal boundary layer what the friction coefficient is to the velocity boundary layer. Thus, the Nusselt number is defined as:

where:

kf is the thermal conductivity of the fluid [W/m.K]

L is the characteristic length

h is the convective heat transfer coefficient [W/m2.K]

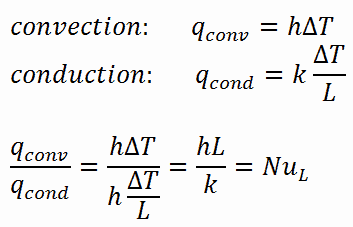

For illustration, consider a fluid layer of thickness L and temperature difference ΔT. Heat transfer through the fluid layer will be by convection when the fluid involves some motion and conduction when the fluid layer is motionless.

In the case of conduction, the heat flux can be calculated using Fourier’s law of conduction. In the case of convection, the heat flux can be calculated using Newton’s law of cooling. Taking their ratio gives:

The preceding equation defines the Nusselt number. Therefore, the Nusselt number represents heat transfer enhancement through a fluid layer due to convection relative to conduction across the same fluid layer. A Nusselt number of Nu=1 for a fluid layer represents heat transfer across the layer by pure conduction. The larger the Nusselt number, the more effective the convection. A larger Nusselt number corresponds to more effective convection, with turbulent flow typically in the 100–1000 range. For turbulent flow, the Nusselt number is usually a function of the Reynolds number and the Prandtl number.[/su_spoiler][/su_accordion]

Laminar Flow

In fluid dynamics, laminar flow is characterized by smooth or regular paths of particles of the fluid, in contrast to turbulent flow, which is characterized by the irregular movement of particles of the fluid. The fluid flows in parallel layers (with minimal lateral mixing), with no disruption between the layers. Therefore the laminar flow is also referred to as streamline or viscous flow.

The term streamline flow is descriptive of the flow because, in laminar flow, layers of water flow over one another at different speeds with virtually no mixing between layers. Fluid particles move in definite and observable paths or streamlines.

When a fluid is flowing through a closed channel such as a pipe or between two flat plates, either of two types of flow (laminar flow or turbulent flow) may occur depending on the velocity, viscosity of the fluid, and the size of the pipe. Laminar flow tends to occur at lower velocities and high viscosity. On the other hand, the turbulent flow tends to occur at higher velocities and low viscosity.

Since the laminar flow is common only in cases where the flow channel is relatively small, the fluid moves slowly, and its viscosity is relatively high, laminar flow is not common in industrial processes. Most industrial flows, especially those in nuclear engineering, are turbulent. Nevertheless, laminar flow occurs at any Reynolds number near solid boundaries in a thin layer adjacent to the surface. This layer is usually referred to as the laminar sublayer. It is very important in heat transfer.

See also: Reynolds Number

See also: Critical Reynolds Number

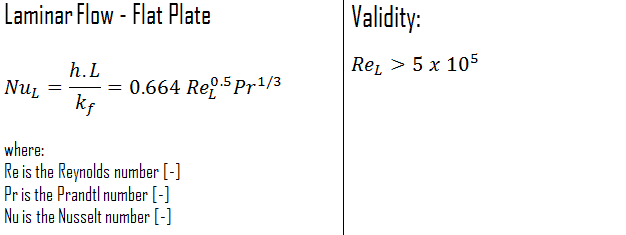

External Laminar Flow – Nusselt Number

The average Nusselt number over the entire plate is determined by:

This relation gives the average heat transfer coefficient for the entire plate when the flow is laminar over the entire plate.

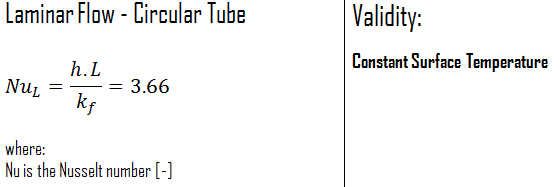

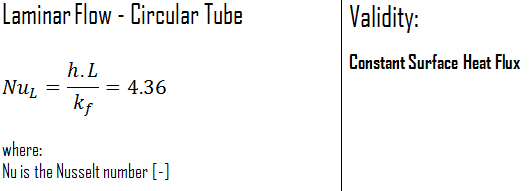

Internal Laminar Flow – Nusselt Number

Constant Surface Temperature

In laminar flow in a tube with constant surface temperature, both the friction factor and the heat transfer coefficient remain constant in the fully developed region.

Constant Surface Heat Flux

Therefore, for fully developed laminar flow in a circular tube subjected to constant surface heat flux, the Nusselt number is a constant. There is no dependence on the Reynolds or the Prandtl numbers.

Turbulent Flow

In fluid dynamics, turbulent flow is characterized by the irregular movement of particles (one can say chaotic) of the fluid. In contrast to laminar flow, the fluid does not flow in parallel layers, the lateral mixing is very high, and there is a disruption between the layers. Turbulence is also characterized by recirculation, eddies, and apparent randomness. In turbulent flow, the speed of the fluid at a point is continuously changing in both magnitude and direction.

Detailed knowledge of the behavior of turbulent flow regimes is important in engineering because most industrial flows, especially those in nuclear engineering, are turbulent. Unfortunately, the highly intermittent and irregular character of turbulence complicates all analyses, and turbulence is often the “last unsolved problem in classical mathematical physics.”

The main tool available for their analysis is CFD analysis. CFD is a branch of fluid mechanics that uses numerical analysis and algorithms to solve and analyze problems that involve turbulent fluid flows. It is widely accepted that the Navier–Stokes equations (or simplified Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations) can exhibit turbulent solutions, and these equations are the basis for essentially all CFD codes.

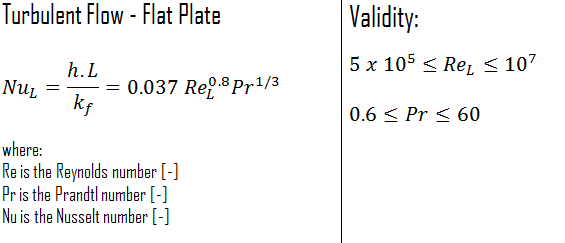

External Turbulent Flow – Nusselt Number

The average Nusselt number over the entire plate is determined by:

This relation gives the average heat transfer coefficient for the entire plate only when the flow is turbulent over the entire plate or when the laminar flow region of the plate is too small relative to the turbulent flow region.

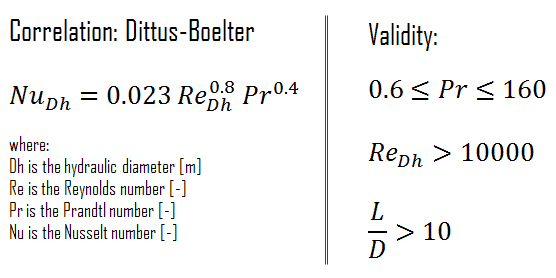

Internal Turbulent Flow – Nusselt Number

See also: Dittus-Boelter Equation

For fully developed (hydrodynamically and thermally) turbulent flow in a smooth circular tube, the local Nusselt number may be obtained from the well-known Dittus-Boelter equation. The Dittus-Boelter equation is easy to solve but is less accurate when there is a large temperature difference across the fluid and is less accurate for rough tubes (many commercial applications) since it is tailored to smooth tubes.

The Dittus-Boelter correlation may be used for small to moderate temperature differences, Twall – Tavg, with all properties evaluated at an, averaged temperature Tavg.

For flows characterized by large property variations, the corrections (e.g., a viscosity correction factor μ/μwall) must be considered, for example, as Sieder and Tate recommend.

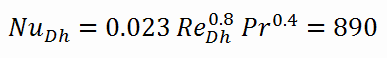

Calculation of the Nusselt number using Dittus-Boelter equation

For fully developed (hydrodynamically and thermally) turbulent flow in a smooth circular tube, the local Nusselt number may be obtained from the well-known Dittus-Boelter equation.

To calculate the Nusselt number, we have to know:

- the Reynolds number, which is ReDh = 575600

- the Prandtl number, which is Pr = 0.89

The Nusselt number for the forced convection inside the fuel channel is then equal to: