In physics, a fluid is a substance that continually deforms (flows) under applied shear stress. Fluids are a subset of the phases of matter and include liquids, gases, plasmas, and, to some extent, plastic solids. Because the intermolecular spacing is much larger and the motion of the molecules is more random for the fluid state than for the solid-state, thermal energy transport is less effective. The thermal conductivity of gases and liquids is generally smaller than that of solids. In liquids, thermal conduction is caused by atomic or molecular diffusion. In gases, thermal conduction is caused by the diffusion of molecules from a higher energy level to a lower level.

Thermal Conductivity of Gases

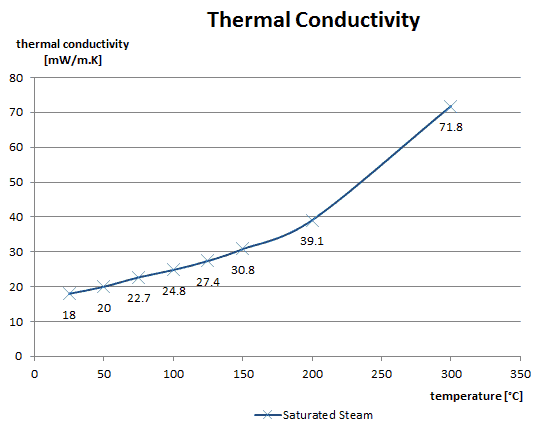

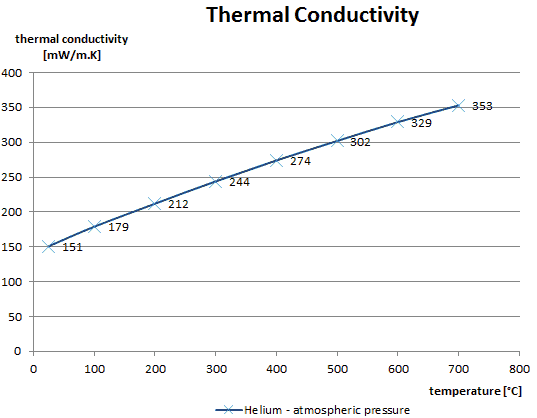

The effect of temperature, pressure and chemical species on the thermal conductivity of a gas may be explained in terms of the kinetic theory of gases. Air and other gases are generally good insulators in the absence of convection. Therefore, many insulating materials (e.g., polystyrene) function simply by having a large number of gas-filled pockets, which prevent large-scale convection. Alternation of gas pocket and solid material causes heat to transfer through many interfaces, causing a rapid decrease in heat transfer coefficient.

The effect of temperature, pressure and chemical species on the thermal conductivity of a gas may be explained in terms of the kinetic theory of gases. Air and other gases are generally good insulators in the absence of convection. Therefore, many insulating materials (e.g., polystyrene) function simply by having a large number of gas-filled pockets, which prevent large-scale convection. Alternation of gas pocket and solid material causes heat to transfer through many interfaces, causing a rapid decrease in heat transfer coefficient.

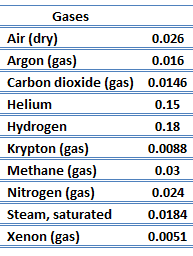

The thermal conductivity of gases is directly proportional to the density of the gas, the mean molecular speed, and especially to the mean free path of a molecule. The mean free path also depends on the diameter of the molecule, with larger molecules more likely to experience collisions than small molecules, which is the average distance traveled by an energy carrier (a molecule) before experiencing a collision. Light gases, such as hydrogen and helium, typically have high thermal conductivity, and dense gases such as xenon and dichlorodifluoromethane have low thermal conductivity.

In general, the thermal conductivity of gases increases with increasing temperature.

Thermal Conductivity of Liquids

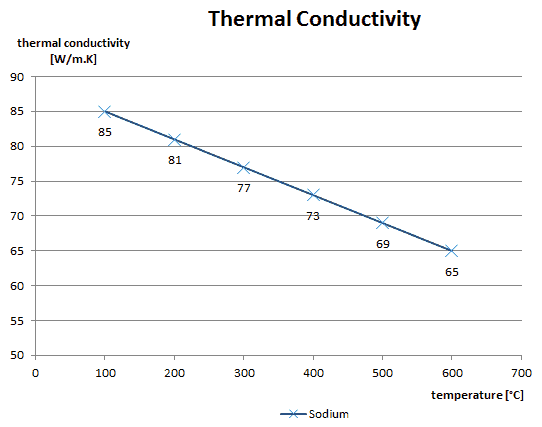

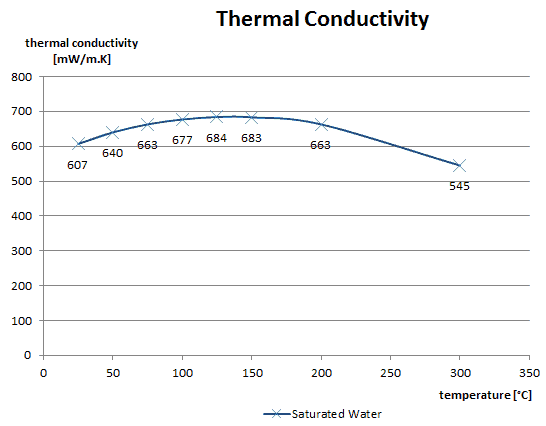

As was written, in liquids, the thermal conduction is caused by atomic or molecular diffusion, but physical mechanisms for explaining the thermal conductivity of liquids are not well understood. Liquids tend to have better thermal conductivity than gases, and the ability to flow makes a liquid suitable for removing excess heat from mechanical components. The heat can be removed by channeling the liquid through a heat exchanger. The coolants used in nuclear reactors include water or liquid metals, such as sodium or lead.

The thermal conductivity of nonmetallic liquids generally decreases with increasing temperature.