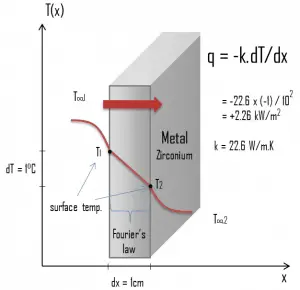

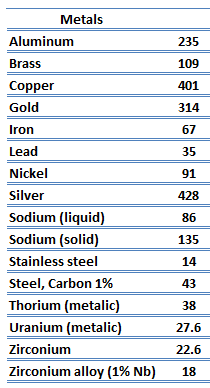

Zirconium is a lustrous, grey-white, strong transition metal that resembles hafnium and, to a lesser extent, titanium. Zirconium is mainly used as a refractory and opacifier, although small amounts are used as an alloying agent for strong corrosion resistance. Zirconium alloy (e.g., Zr + 1%Nb) is widely used as a cladding for nuclear reactor fuels. The desired properties of these alloys are a low neutron-capture cross-section and resistance to corrosion under normal service conditions. Zirconium alloys have lower thermal conductivity (about 18 W/m.K) than pure zirconium metal (about 22 W/m.K).

Special reference: Thermophysical Properties of Materials For Nuclear Engineering: A Tutorial and Collection of Data. IAEA-THPH, IAEA, Vienna, 2008. ISBN 978–92–0–106508–7.

Thermal Conductivity of Metals

Metals are solids, and as such, they possess a crystalline structure where the ions (nuclei with their surrounding shells of core electrons) occupy translationally equivalent positions in the crystal lattice. Metals, in general, have high electrical conductivity, high thermal conductivity, and high density. Accordingly, transport of thermal energy may be due to two effects:

Metals are solids, and as such, they possess a crystalline structure where the ions (nuclei with their surrounding shells of core electrons) occupy translationally equivalent positions in the crystal lattice. Metals, in general, have high electrical conductivity, high thermal conductivity, and high density. Accordingly, transport of thermal energy may be due to two effects:

- the migration of free electrons

- lattice vibrational waves (phonons).

When electrons and phonons carry thermal energy leading to conduction heat transfer in a solid, the thermal conductivity may be expressed as:

k = ke + kph

As far as their structure is concerned, the unique feature of metals is the presence of charge carriers, specifically electrons. The electrical and thermal conductivities of metals originate from the fact that their outer electrons are delocalized. Their contribution to the thermal conductivity is referred to as the electronic thermal conductivity, ke. In fact, in pure metals such as gold, silver, copper, and aluminum, the heat current associated with the flow of electrons by far exceeds a small contribution due to the flow of phonons. In contrast, for alloys, the contribution of kph to k is no longer negligible.