Source: wikipedia.org CC BY-SA

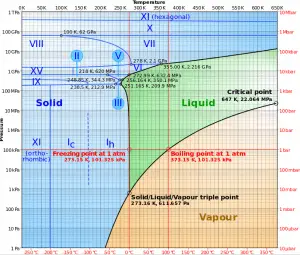

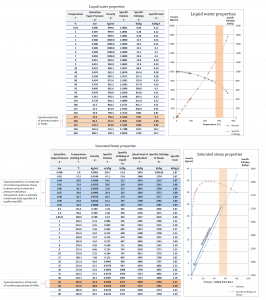

As seen from the phase diagram of water, in the two-phase regions (e.g.,, on the border of vapor/liquid phases), specifying temperature alone will set the pressure, and specifying pressure will set the temperature.

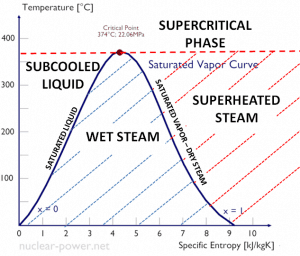

- The saturation vapor curve separates the two-phase state and the superheated vapor state in the T-s diagram.

- The saturated liquid curve separates the subcooled liquid state and the two-phase state in the T-s diagram.

If steam exists entirely as vapor at saturation temperature, it is called saturated vapor, saturated steam, or dry steam. The dry saturated vapor is characterized by the vapor quality, which is equal to unity. Superheated vapor or superheated steam is a vapor at a temperature higher than its boiling point at the absolute pressure where the temperature is measured. The pressure and temperature of superheated vapor are independent properties since the temperature may increase while the pressure remains constant. The substances we call gases are highly superheated vapors.

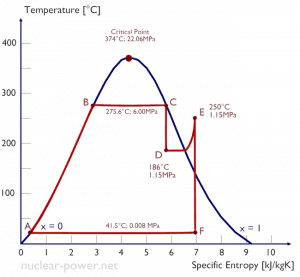

The process of superheating water vapor in the T-s diagram is provided in the figure between state E and the saturation vapor curve. As can be seen, also wet steam turbines use superheated steam, especially at the inlet of low-pressure stages. The enthalpy must be obtained from the superheated steam tables to evaluate the cycle thermal efficiency.

The superheating process is the only way to increase the peak temperature of the Rankine cycle (and to increase efficiency) without increasing the boiler pressure. This requires the addition of another type of heat exchanger called a superheater, which produces the superheated steam.

In the superheater, further heating at fixed pressure results in increases in both temperature and specific volume. The process of superheating in the T-s diagram is provided in the figure between state E and the saturation vapor curve.

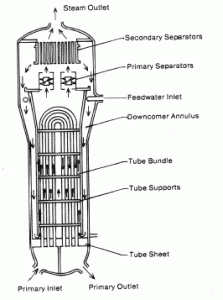

Typically most nuclear power plants operate multi-stage condensing steam turbines. In these turbines, the high-pressure stage receives steam (this steam is nearly saturated steam – x = 0.995 – point C at the figure) from a steam generator and exhausts it to a moisture separator-reheater (point D). The steam must be reheated or superheated to avoid damages caused to the blades of the steam turbine by low-quality steam. The high content of water droplets can cause rapid impingement and erosion of the blades, which occurs when condensed water is blasted onto the blades. To prevent this, condensate drains are installed in the steam piping leading to the turbine. The reheater heats the steam (point D), and then the steam is directed to the low-pressure stage of the steam turbine, where it expands (point E to F). The exhausted steam is well below atmospheric pressure and is in a partially condensed state (point F), typically of a quality near 90%.

Vapor Quality – Dryness Fraction

As seen from the phase diagram of water, in the two-phase regions (e.g.,, on the border of vapor/liquid phases), specifying temperature alone will set the pressure, and specifying pressure will set the temperature. But these parameters will not define the volume and enthalpy because we will need to know the relative proportion of the two phases present.

As seen from the phase diagram of water, in the two-phase regions (e.g.,, on the border of vapor/liquid phases), specifying temperature alone will set the pressure, and specifying pressure will set the temperature. But these parameters will not define the volume and enthalpy because we will need to know the relative proportion of the two phases present.

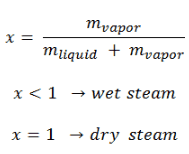

The mass fraction of the vapor in a two-phase liquid-vapor region is called the vapor quality (or dryness fraction), x, and it is given by the following formula:

The value of the quality ranges from zero to unity. Although defined as a ratio, the quality is frequently given as a percentage. From this point of view, we distinguish between three basic types of steam. It must be added, at x=0, we are talking about the saturated liquid state (single-phase).

This classification of steam has its limitation. Consider the system’s behavior, which is heated at a pressure that is higher than the critical pressure. In this case, there would be no change in phase from liquid to steam. In all states, there would be only one phase. Vaporization and condensation can occur only when the pressure is less than the critical pressure. The terms liquid and vapor tend to lose their significance.

See also: Saturation

Properties of Steam – Steam Tables

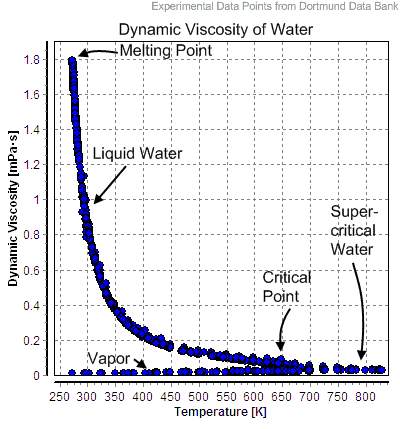

Water and steam are common fluids used for heat exchange in the primary circuit (from the surface of fuel rods to the coolant flow) and in the secondary circuit. It is used due to its availability and high heat capacity, both for cooling and heating. It is especially effective to transport heat through vaporization and condensation of water because of its very large latent heat of vaporization.

A disadvantage is that water-moderated reactors have to use the high-pressure primary circuit to keep water in the liquid state and achieve sufficient thermodynamic efficiency. Water and steam also react with metals commonly found in industries such as steel and copper, oxidized faster by untreated water and steam. In almost all thermal power stations (coal, gas, nuclear), water is used as the working fluid (used in a closed-loop between boiler, steam turbine, and condenser), and the coolant (used to exchange the waste heat to a water body or carry it away by evaporation in a cooling tower).

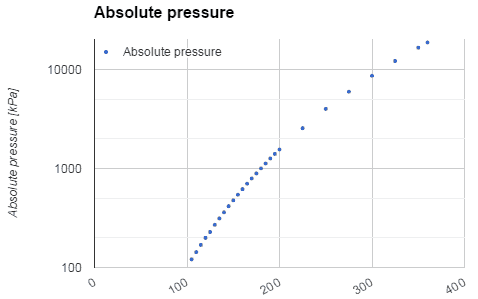

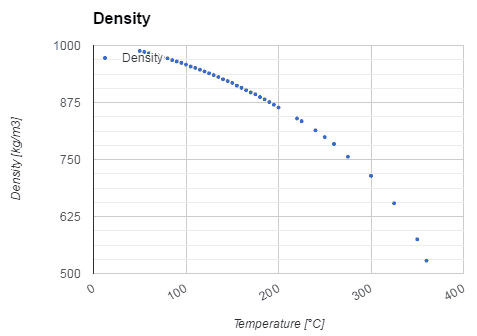

Water and steam are common medium because their properties are very well known. Their properties are tabulated in so-called “Steam Tables”. In these tables, the basic and key properties, such as pressure, temperature, enthalpy, density, and specific heat, are tabulated along the vapor-liquid saturation curve as a function of both temperature and pressure. The properties are also tabulated for single-phase states (compressed water or superheated steam) on a grid of temperatures and pressures extending to 2000 ºC and 1000 MPa.

Further comprehensive, authoritative data can be found at the NIST Webbook page on thermophysical properties of fluids.

See also: Steam Tables.

Special Reference: Allan H. Harvey. Thermodynamic Properties of Water, NISTIR 5078. Retrieved from https://www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/srd/NISTIR5078.htm