Stress

In mechanics and materials science, stress (represented by a lowercase Greek letter sigma – σ) is a physical quantity that expresses the internal forces that neighboring particles of a continuous material exert on each other. At the same time, strain is the measure of the deformation of the material, which is not a physical quantity.

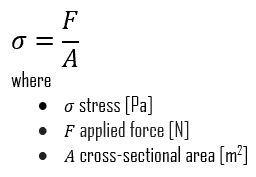

Although it is impossible to measure the intensity of this stress, the external load and the area to which it is applied can be measured. Stress (σ) can be equated to the load per unit area or the force (F) applied per cross-sectional area (A) perpendicular to the force as:

When a metal is subjected to a load (force), it is distorted or deformed, no matter how strong the metal or light the load. If the load is small, the distortion will probably disappear when the load is removed. The intensity, or degree, of distortion, is known as strain. A deformation is called elastic deformation if the stress is a linear function of strain. In other words, stress and strain follow Hooke’s law. Beyond the linear region, stress and strain show nonlinear behavior. This inelastic behavior is called plastic deformation.

Stress is the internal resistance, or counterforce, of a material to the distorting effects of an external force or load. These counterforces tend to return the atoms to their normal positions. The total resistance developed is equal to the external load.

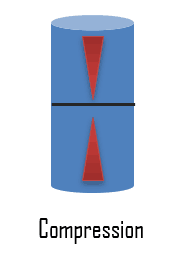

Compressive Stress

From an internal point of view, stress intensity within the body of a component is expressed as one of three basic internal load types: tension, compression, and shear. In engineering practice, many loads are torsional rather than pure shear. Mathematically, there are only two types of an internal load because tensile and compressive stress may be regarded as the positive and negative versions of the same type of normal loading.

From an internal point of view, stress intensity within the body of a component is expressed as one of three basic internal load types: tension, compression, and shear. In engineering practice, many loads are torsional rather than pure shear. Mathematically, there are only two types of an internal load because tensile and compressive stress may be regarded as the positive and negative versions of the same type of normal loading.

Compressive stress is the reverse of tensile stress. Adjacent parts of the material tend to press against each other through a typical stress plane. Compressive stress to bars, columns, etc., leads to shortening. Compressive stress is defined similarly to tensile stress but has negative values to express the compression since delta L has the opposite direction. One can increase the compressive stress until compressive strength is reached. Then materials will react with ductile behavior or with a fracture in the case of brittle materials. Because tensile and compressive loads produce stresses that act across a plane in a direction perpendicular (normal) to the plane, tensile and compressive stresses are called normal stresses. The ability of a material to react to compressive stress or pressure is called compressibility.